The Siy Gospel’s (1692) illustrations

Exploring the Siy Gospel (1692) illustrations

By Anna Chemisova

Project Synopsis

The Siy Gospel of 1692 is an outstanding example of the Orthodox manuscript tradition, almost unknown to researchers outside Russia. The project’s purpose is to delve into the manuscript’s illustrations, explore their artistic merit and historical significance. The Gospel’s illustrations reflect the changes that took place in the Russian iconography in the second half of the 17th century.

| Categories | Bible |

| Title | The Siy Gospel |

|---|---|

| Date | 1680 — no later than 1692 |

| Place | Moscow, Russia |

| Contributor(s) | Artists: multiple, unknown. Some of the illustrations allegedly were made by Nicodemus, archimandrite of the Antoniev-Siya monastery. Scribes: allegedly two, unknown. |

| Language(s) | Old Church Slavonic |

| Source | Digital local history library: Russian North |

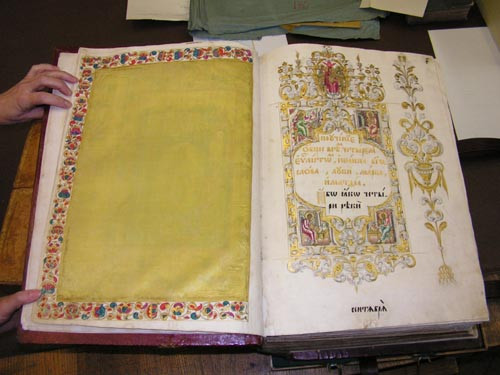

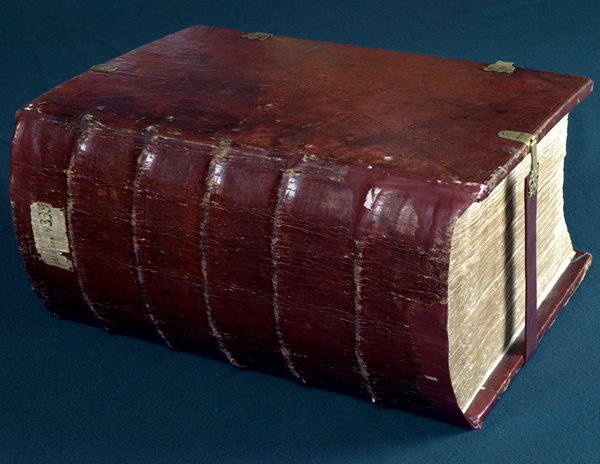

| Format | In-folio (44.5 x 32 cm), 945 pp. |

Introduction to the Bible

The Siy Gospel is aprakos, in other words service or weekly Gospel. In the context of Russian Orthodox Christianity it refers to a specific type of liturgical book that is arranged according to the church calendar rather than sequentially. The texts of the Gospel are assembled not in the order in which they appear in the New Testament, but according to when they are read in the church services throughout the year. Each reading is matched to a specific feast day or a particular Sunday.

The manuscript’s given name refers to the place where it was conserved, and the year 1692 indicates the year it was donated to the monastery. The Siya Monastery was founded by St. Antonius in 1520 on the river of the same name in the northern part of Russia. It immediately became one of the centres of Orthodox church, book culture and book-learning in the region.

After the manuscript was presented to the monastery by a patriarchal treasurer Paisius, it served as the Gospel book kept in a central place on the Holy Table (altar). Judging by its appearance, it was handled very carefully, probably being used only during religious celebrations. Researchers discovered it only in the second half of the 19th century.

Illustrations’ description

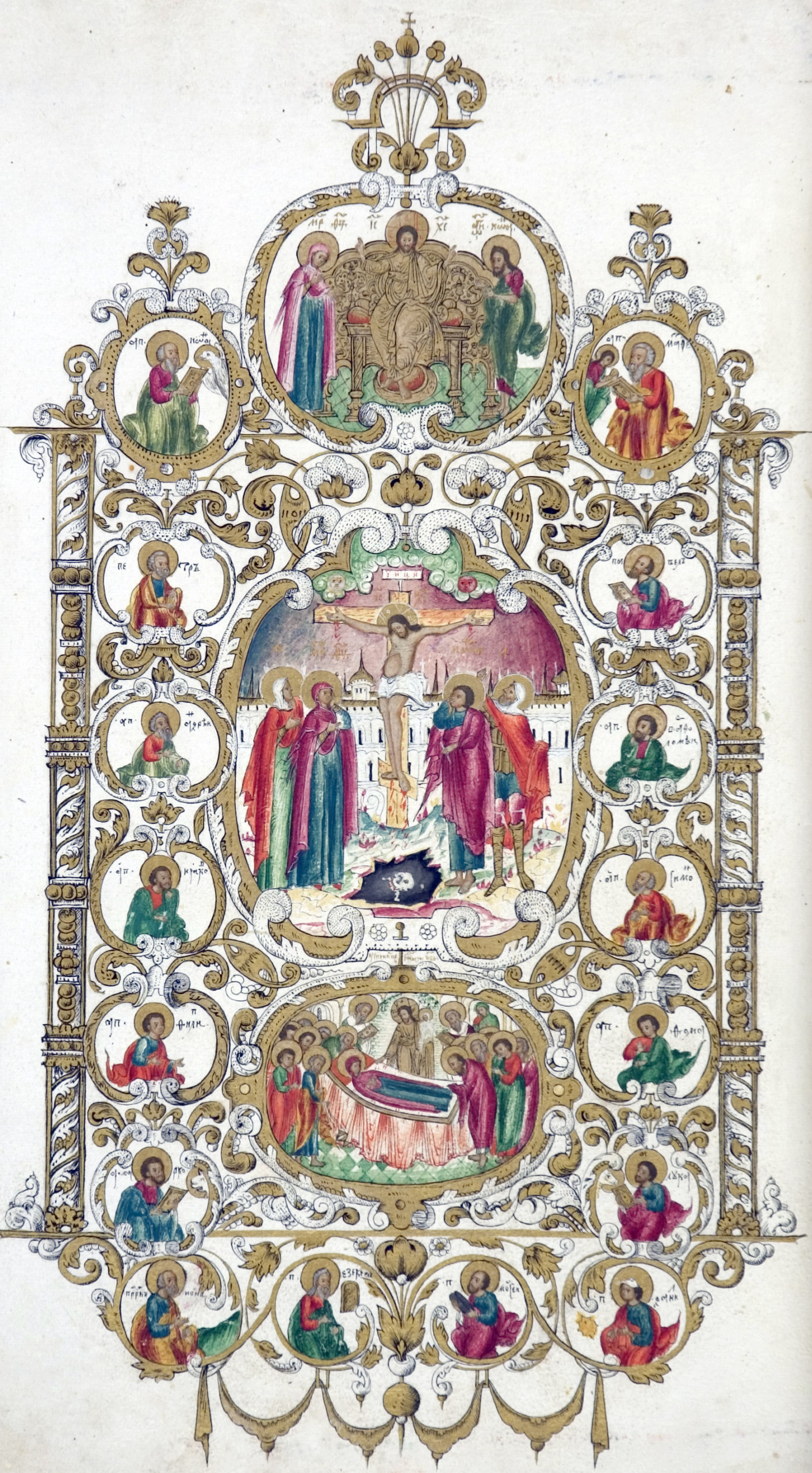

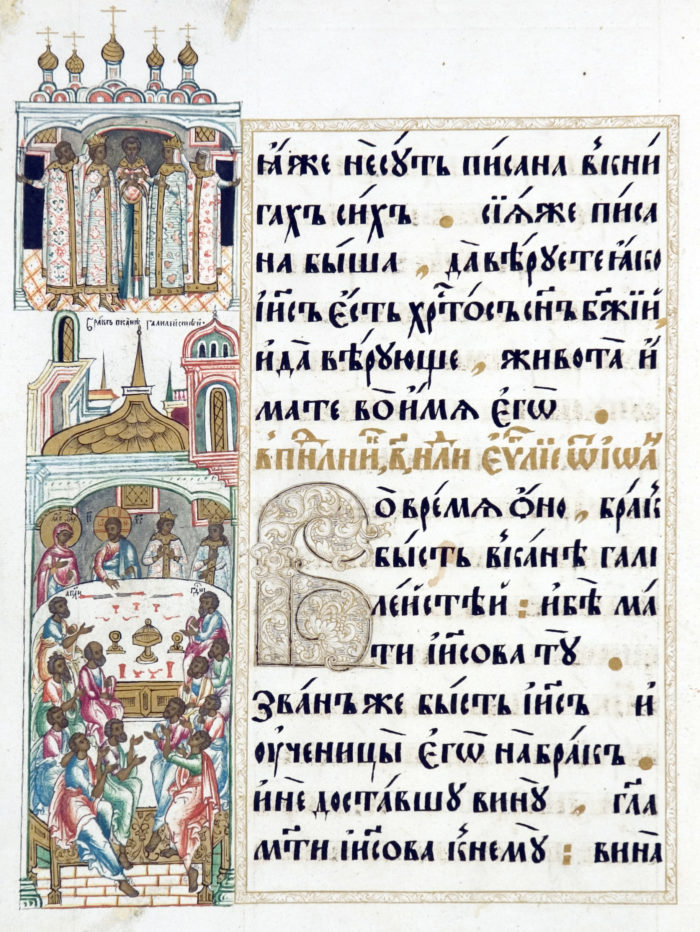

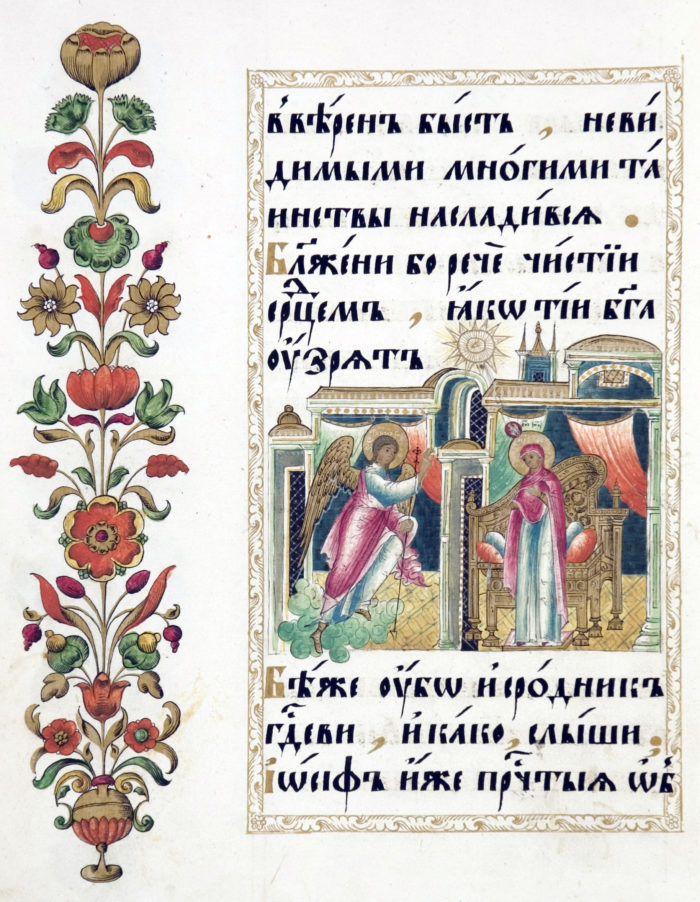

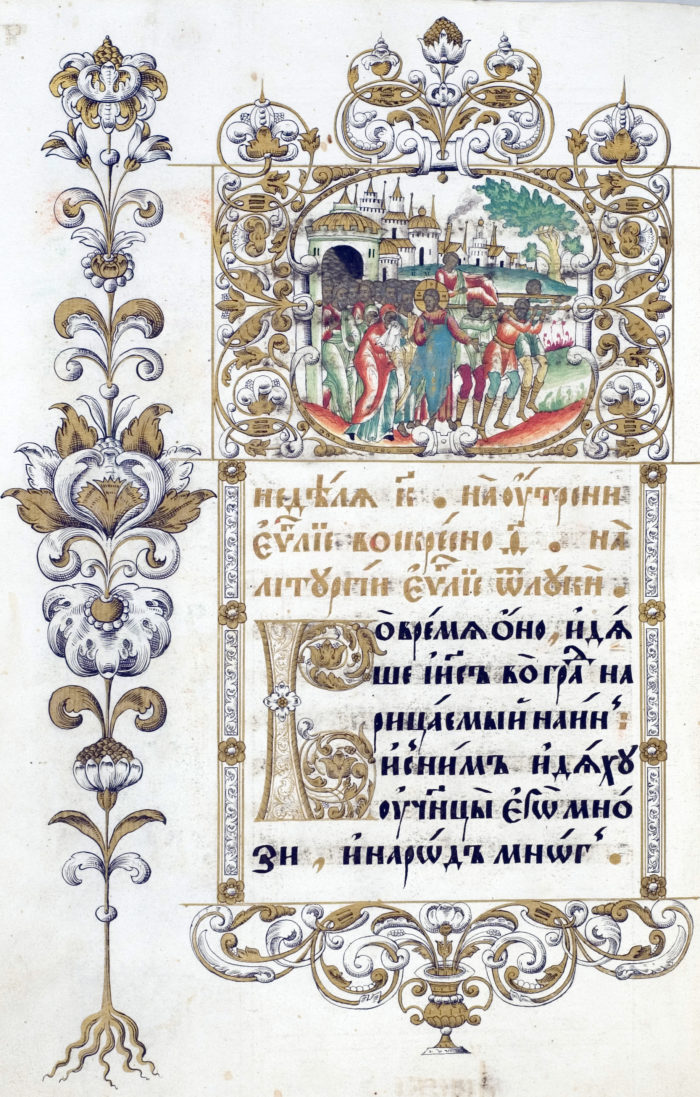

The Gospel includes over three thousand illustrations. Among them are ornaments on margins, miniatures, folio illustrations, decorated letters and cursive. Researchers agree that the group of artists consisted of both experienced professionals of the Moscow painting school and monastic provincial artists. The former were responsible for large illustrations, ornaments in the late Renaissance style, Cyrillic calligraphy, while the latter created only miniatures and small ornaments.

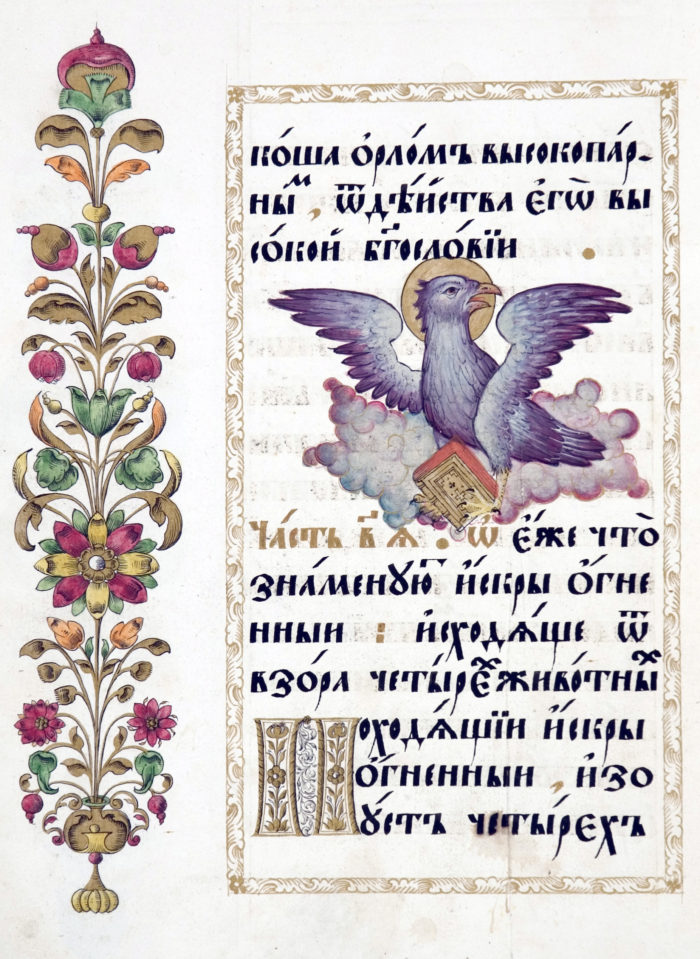

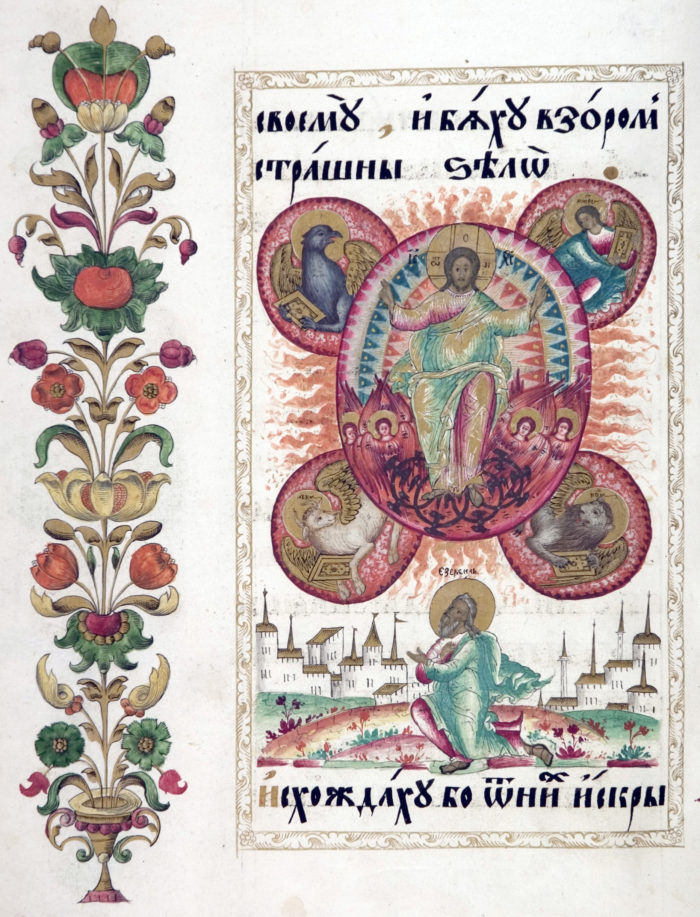

Images of evangelists

In the Siy Gospel they are arranged in the following order: John, Matthew, Mark, Luke. The images are in full page, executed expertly and vividly. Gold, red and blue colors predominate. There are many details in the foreground and background, the faces are carefully drawn making the evangelists look “volumetric” and “relief”. On the next page there is a symbol corresponding to each of the evangelists. This is a completely atypical solution for the Gospel book at this period. Much more common for the second half of the 17th century are the images of the evangelists in one composition with their symbols.

In the illustration above, the image of John is accompanied by the figure of an eagle. Before this drawing, almost at the beginning of the manuscript, there is a page on which the scribe emphasizes separately that he considers the eagle, not the lion, to be the symbol of John.

The record proves that at the end of the 17th century there was no consensus about this issue. This state of affairs was caused, particularly in our case, by the recent church schism (1666–1667). Apparently, at that time the question about evangelists’ depiction took on a dogmatic turn. The Old Believers considered Ezekiel’s interpretation to be the truthful one. In this explanation, John is symbolized by a lion, Mark by an eagle, Matthew by an angel, and Luke by a calf. This interpretation of Ezekiel’s prophecy goes back to Irenaeus, the bishop of Lugdunum (Lyon).

Which is more interesting on one of the other page depicting Jesus with all evangelists it is the other way around – Mark is symbolized by an eagle, John by a lion.

It turns out that even though the manuscript was commissioned by the official church and adhered to its side in interpreting the symbols of the evangelists, there was still confusion in John’s and Mark’s attributes.

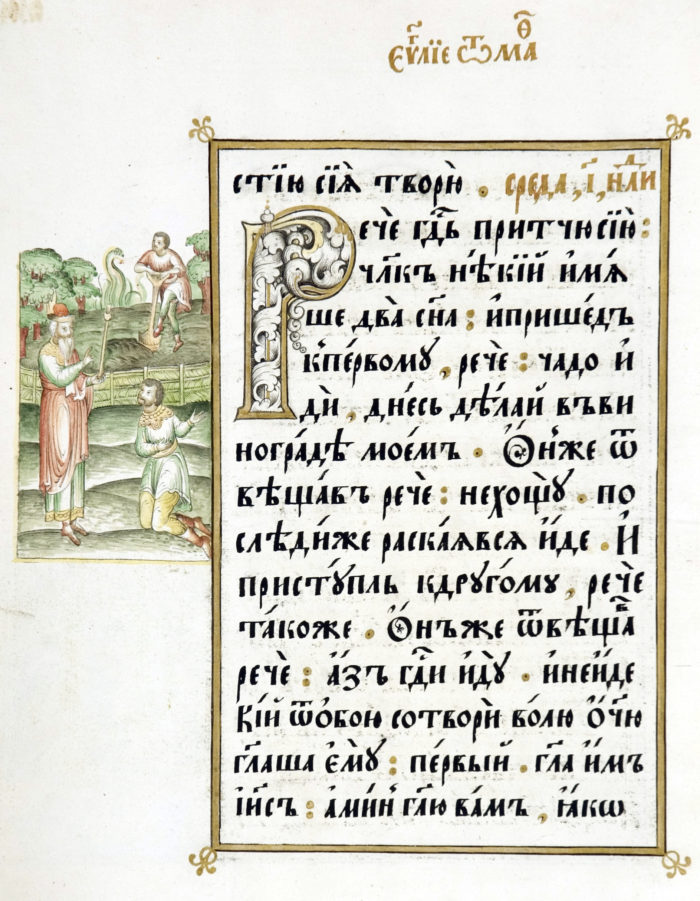

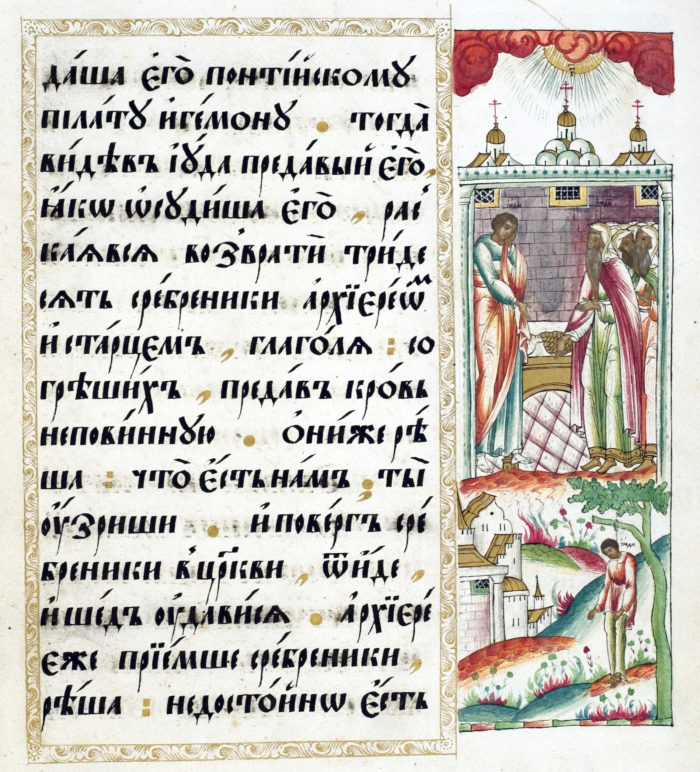

Miniatures

Margin miniatures are a rather unusual type of illumination for the Gospels. Nevertheless, the Siy Gospel contains many of them. Miniaturists followed the scribes. In other words, the illustrations follow the text on the page and do not deviate from the narrative. Miniatures differ in quality: detailed ones are made by experienced iconographers, while others are realized more simply and straightforwardly. What they have in common is an abundance of different motifs: byzantine, old-printed, late Renaissance – they add a baroque flavor to the illustrations. A storm of colors, lines, details is noticeable even in the small narrative miniatures. These are no longer strict biblical illustrations, but slightly more free and even secular.

The Siy Gospel is without doubt a remarkable manuscript. It has no equal in the number of miniatures, the choice and realization of drawn scenes also distinguish it from earlier Gospels. Familiarity with the Western school had a greater impact on the stylistics of the miniatures, enriching the compositions with mundane details, enlivening static figures, and a freer painting style. However, the Russian Orthodox motifs are seen everywhere: in the forms, clear and definite, in the features of churches with onion domes and crosses.

Bibliography

- Bratchikova, Elena. “A 17th century Siy Gospel (inscriptions and illuminations).” [In Russian.] In Chrysograph. Medieval book centres: local traditions and inter-regional connections Vol. 3, edited by Elina Dobrynina, 310–321. Moscow: Scanrus, 2009.

- Bratchikova, Elena. “A fine example of Old Russian painting and writing.” [In Russian.] Digital local history library: Russian North. November 19, 2023. https://ekb.aonb.ru/se/glava2/glava2.htm.

- Bratchikova, Elena. “A significant monument of Russian art and iconography.” [In Russian.] Digital local history library: Russian North. November 19, 2023. https://ekb.aonb.ru/se/glava3/glava3.htm.

- Bratchikova, Elena. “On the history of the creation of the Siy Gospel of the XVII century.” [In Russian.] Papers of the Department of Old Russian Literature Vol. 53 (2003): 602–613.

- Bratchikova, Elena. “The 17th century Siy Gospel and late Medieval painting tradition.” [In Russian.] In Monuments of Culture: New Discoveries, edited by Boris Rauschenbach, 201–223. Moscow: Nauka, 2002.

- Buslaev, Fyodor. “Literature of Russian iconographic originals.” [In Russian.] In Old Russian Folk Literature and Art, edited by Fyodor Buslaev, 330–391. St.-Petersburg: The publication of D.E. Kozhanchikov, 1861.

- Pokrovskiy, Nikolay. The Gospel in iconographic sources, mainly Byzantine and Russian ones. [In Russian.] St.-Petersburg: Typography of the Udelov’s Department, 1849.

Photo credits: all Gospel photo rights belong to the Digital local history library: Russian North.