Geneva Bible

The publication of the most popular English Bible of the 16th century and its impact on defining women’s status in society

by Monia Teffah & Diego Rodriguez

| Title: | Bible and Holy Scriptvres conteyned in the Olde and Newe Testament. Translated according to the Ebrue and Greke, and conferred with the best translations in diuers langages… |

| Contributors: | Whittingham, William, -1579; Gilby, Anthony, c1510-1585; Sampson, Thomas, 1517?-1589. |

| Publisher: | Printed by Rouland Hall |

| Place: | Geneva |

| Date: | 1560 |

| Language: | English |

Physical description

Few copies exist as part of private collections in Libraries such as the Bodleian Library. However, we know what the physical aspect of the first edition of the Geneva Bible through the description made by Darlow, Thomas Herbert, Moule, (Horace Frederick), and Jayne, Arthur Barland in the Historical catalogue of the printed editions of Holy Scripture in the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society. Volume 1.

Four preliminary leaves : title (with woodcut), on verso The names and order of all the bookes . . ., Epistle: To the moste Vertvovs and Noble Qvene Elisabet, Queue of England, France, ad Ireland, de. Your humble subiects of the English Churche at Geneva, wish grace andpeace from God the Father through Christ lesus our Lord—2 S., Address : To ovr Beloved in the Lord the Brethren of England,

Scotland, Ireland, de. Grace, mercie and peace, through Christ lesus—1 f. (Both the Epistle and the Address are dated From Geneua. 10. April. 1560.) The text: (1) O. T. and Apocrypha, ff. 1 to 474 (Bbbbb iiii) a, verso blank ; (2) N. T., with title : The Newe Testament of ovr Lord lesvs Christ, Conferred diligently with the Greke, and best approved translatons in diuers languages. At Geneva. Printed by Rouland Hall. M.D.LX. (with cut), verso blank, text—ff. 2 to 122 (HHh ii) a, verso blank ; followed by A brief table of the interpretation of the propre names …, A table of the principal things …, A perfite supputation . . . (with a text at the end loshva Chap. 1. vers. S. Let not this boke . . . good successe), and The order of the yeres from Pauls conversion shewing the time of his peregrination, £ of his Epistles writen to the Churches,—27 pp., ending on LL1 iiii a, verso blank.

Signatures: « a-z A-Z4 Aa-Zz4 &• Aaa-Zzz4 Aaaa-Zzzz* Aaaaa4 Bbbbb, AA-ZZ AA&-LL14; 614 ff. Printed in roman type; double columns, divided into verses. Marginal notes in very small roman type. References etc.. and “contents” before chapters in italics. Subject headings in headlines. An argument is prefixed to each book. The Hebrew names are carefully spelt and accented, e.g. laakób, Izhák, Bebekfih, etc. In Ecêlus. xv. 13 occurs the following error (a negative omitted) :—The Lord hateth all abominación [of erreur:] and they thatfeare God, wil loue it. The cut on the titlepages represents the crossing of the Bed Sen ; above are the words Feare ye not, stand stil, and beholde the saluadon of the Lord, which he will shewe to you this day. Exod. 14, t3, below—The Lord shal fight far you : therefore holde you yourpeace, Exod. 14, vers. 14, and at tho sides—Great are the troubles of the righteous : | but the Lord deliuereth them out of all, Psal. 34, 19. The engravings in the text number 26, and include a plan The situación of the Garden of Eden, and representations of the Flood, the crossing of the Bed Sea, the Tabernacle and its furniture, the Temple and its furniture, Solomon’s throne, the vision of Ezekiel, etc. ; many of these are accompanied by descriptive notes.. The book contains five maps on separate leaves : (1) at Numbers xxxiii (to illustrate the wanderings of the Israelites), (2) at Joshua xv (the division of the land of Canaan), (3) at the end of Ezekiel (The forme of the Temple and citie restored), (4) in St. Matthew (The description of the holla land . . . wi th a list of places specified . . . with their situation by the obseruation of the degrees concerning their length and breadth), (5) in Acts (The description of the covntreis and places mencioned in the Actes of the Apostles . . . with list of names, etc.).

Context

A. Translating the Bible into English

Before The Great Bible was produced, it was illegal to translate the Bible into English. It was intended to be read exclusively in Latin. However, because most people were unskilled in Latin, they were compelled to rely on the church’s interpretations. It was a viable tactic used by the king and church to maintain control over their subject’s thoughts. If they could read the bible, then they will be able to form their own interpretations and contest the authority of the king and the church. Initiating this was a risky venture for Coverdale and Tyndale. However, After Henry’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon he was no longer a Catholic but a Protestant; therefore, he permitted the Great Bible. It is strongly liable that Anne Boleyn persuaded Henry to change his mind. She is the reason why Henry took his distance from Rome. She was caught with Tyndale’s Obedience of a Christian Man(1528). It was illegal to possess such a text and she could have been burned at the stake for owning such a book. This text was claiming that the King should answer to no one but God, not even the pope. But, Anne went to beg the King for her life and to ask him to read it. After, reading it, Henry was deeply convinced that he should form his own Church, the Church of England. Even before she met Henry, Anne read extensively, which was unusual for most women at the period. Anne was a protestant and thought that people should have equal access to the word of God. In his article, E.W. Ives explained that “First, there does seem to have been some debate in 1535-6 on the use of confiscated monastic wealth. Second, Anne is known to have been actively involved in monastic affairs. Thirdly, she was interested in university education and she was undoubtedly familiar with the campaign of Christian humanism to redirect church wealth to better uses. We have a specific example of her initiative when the deanship of the collegiate church of Stoke by Clare in Suffolk became vacant. She put in her reformist chaplain, Matthew Parker and he transformed the college into a bible-based educational house offering a bursary to Cambridge, with Anne as its new founder.”

B. Like mother like daughter

When Mary Tudor ascended to the throne of England in 1553, her attempts to reverse the protestant reforms that had taken place during the reign of her younger brother Edward VI caused the exodus of English Protestants known as the Marian Exile.

Some of the Protestants were forced to leave the island and congregated in Frankfurt, from where they moved to Geneva in 1555. The most important activity of this congregation was the production of a new English edition of the Bible based on a re-examination of Hebrew, Greek and Latin sources. This cooperative enterprise is believed to have been started in 1558 under the direction of William Whittingham and was produced by John Calvin, John Knox, Myles Coverdale, John Foxe, and other Reformers. No other translation of the Bible into English has been produced during the reign of Mary Tudor.

On the contrary, Queen Elizabeth I was very popular. Her aim was to bring back Protestantism, but she was a very tolerant Queen. Her subjects were free to choose to be either Catholic or Protestant. Like her mother, she was very well-read. She was proficient in six languages: English, French, Greek, Latin, Spanish, and Welsh. She also learned additional languages, including Flemish, Italian, and Gaelic.

The influences

The creation of this Bible was influenced by the reformer’s ideas. Whittingham oversaw work on the Old Testament after finishing the New Testament. He enlisted the assistance of Miles Coverdale, Anthony Gilbey, Christopher Goodman, Thomas Sampson, and William Cole. They worked straight from the Hebrew text to create the first Old Testament that did not rely on the Vulgate.

In addition, “The New Testament is a careful revision of Whittingham’s Testament of 1557 (q.v.), due to a further comparison with Beza’s Latin translation. The Old Testament and Apocrypha are based mainly on the Great Bible, corrected from the original Hebrew and Greek, and compared with the Latin versions of Leo Juda and others; while the influence of the revisers of Olivetan’s French Bible is also apparent.”

Historical catalogue of the printed editions of Holy Scripture in the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society. Volume 1

The purpose

The Geneva Bible was the first “Study bible”. It was remarkable, as it employed a number of methods to aid the reader in studying, comprehending, and interpreting the Bible. For the first time, the script was separated into numbered verses after being translated from the original Hebrew and Greek scriptures. Moreover, each book and chapter began with an “argument” that helped to clarify the meaning of the terms. The marginal notes represented roughly a third of the entire Bible. Some of the notes have actually been preserved for the translation of the King James Bible. These academic comments were used by the translators to reference, clarify unclear interpretations, and educate the reader about the original script. The Geneva Bible was known by many names, one of which was “the Bible of the people.” This Bible is also more impressive compared to the Great Bible. It exchanged Gothic types for Roman types, which made it easier to read. And the Great Bible owned its name from its particularly exceptional size. It was too heavy and hardly transportable compared to the Geneva Bible that could be carried and brought home. Moving from a bible, which format was an in-folio to a bible in-quarto and in later editions, it became an in-octavo. It is also known as the “Shakespearean Bible” because he extensively used mostly marginal notes to write his plays. It served many others, such as John Bunyan in The Pilgrim’s Progress.

The symbolic value

It was the most popular translation of the English Bible even compared to the King James Bible. Even after the King James Bible was published, people still preferred the Geneva Bible. In The King James translations, the marginal notes disappeared. They were considered to diffuse too much Calvinist ideas and also considered anti-papal but overall they were questioning the authority of the King. The Geneva Bible is the symbol of the continuation of a long Protestant Reformation that started during King Henry VIII’s reign. But the Geneva Bible was revolutionary it was also regarded as the “Bible of the people”. The method employed to helped the reader allowed the literacy rate to grow in England. More so that it was also an affordable Bible. Queen Elizabeth I like her mother Anne Boleyn, believed that people should have access to the word of God no matter their social and economic status.

Reception

According to an article published by Naseeb Shaheen in Studies in Bibliography (1984), the Geneva Bible did not become the most popular edition right after its appearance in 1560, the reputation of “the most popular Bible of its time” would rather be built in a very slow pace due to the bureaucratic obstacles set for its printing in English soil. When John Bodley received in 1560 an exclusive patent to print the Geneva Bible for seven years from Queen Elizabeth, he did not know that the edition would have to be approved by the Bishops of Canterbury, nor that the task would take sixteen years to be accomplished. The patent given to the father-to-be of the Bodleian library to print the Geneva Bible turned out to be fruitless when facing the position of the Archbishop Parker (1504-1575), co-founder of the Anglican theological thought, who constantly discouraged the publication of this work due to its “bitter notes”. Eventually the patent would be extended while waiting for the edition to be approved, but no Geneva Bible was printed by an English press until the death of Archbishop Parker.

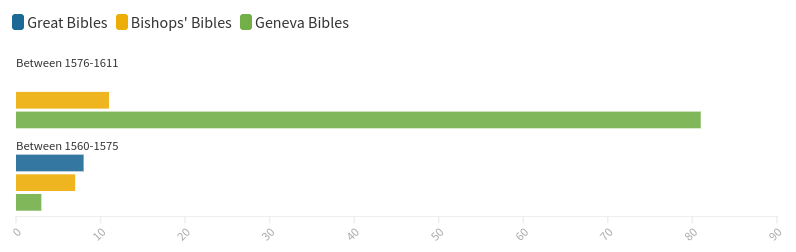

Before the printing of the Geneva Bible was possible in England, out of the eighteen editions of complete Bibles published between 1560 and 1575, eight were Great Bibles, seven were Bishops’ and three were Genevas (printed in Geneva). But once the printing of the Geneva Bible was finally possible in England, the selling of its copies was superior to the others that were sold. Between 1576, when the first Geneva Bible was printed in England, and 1611, when Shakespeare’s dramatic career was almost over and the King James Bible appeared, ninety-two editions were published in England, eighty-one were Genevas and eleven Bishops’.

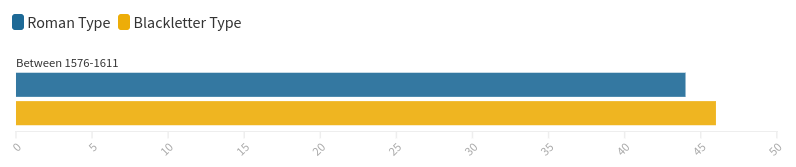

The first black letter edition of the Geneva Bible was printed in 1578, between this first appearance and 1595, twenty-four editions were printed in black letter while nineteen were printed in roman. In total, the popularity of the black letter type is slightly superior to the roman type, since the publication of the first edition in 1560 until its last in 1616, forty-six were printed in black letter and forty-four in roman type.

Weaponizing the Bible

The impact of this Bible was crucial for the interpretation of women’s status in the 17th century. In 1617, a man called Joseph Swetnam published The Woman-Hater Arraigned by Women. This play was used by Swetnam to claim that women have been tainted since the creation of Eve because Eve enticed Adam to eat the apple, causing him to commit a sin. Swetnam further claims that the woman is crooked because she was created from a rib and that those women are merely a burden to men because their sole duty is to waste all of the man’s fortune.

Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 5697 fol. 16r. (detail of God creating Eve from Adam’s rib).

But, this year was also the one of the publications of three other pamphlets: A Mouzell for Melastomus by Rachel Speght, The vvorming of a mad dogge: or, A soppe for Cerberus the iaylor of Hell. No confutation but a sharpe redargution of the bayter of women. By Constantia Munda and finally, Ester Hath Hanged Haman: or an answere to a lewd pamphlet, entituled, the arraignment of women, with the arraignment of lewd, idle, froward, and unconstant men, and husbands by Ester Sowernam. In those three pamphlets Speght, Munda and Sowernam answer to the misogynist attack made by Swetnam in his play. In their pamphlet, they take the defence in the name of the women’s sex or as the person of Eve’s sex. Their argument was that they have been insulted as women but more importantly, blasphemed as a creature of God. Their strategy was to use passages from the Bible as a weapon to defend their status as women. One of the most important passages is about the creation of Eve. For them, Eve was not created from the head of Adam so women are not superior. Eve was not created from the feet of Adam so they are not inferior to men but from the rib meaning closer to the heart. Therefore, women are equal to men. Until before 1617, men used to Bible as a justification for their superiority to women but now that some women were educated, they used it too. There is not enough proof, but probably that Rachel Speght used the Geneva Bible. In her article “Rachel Speght and the ‘Criticall Reader’”, Christina Luckyj says that “because Speght was a Calvinist, it is extremely likely that she had access to the Geneva Bible, as well as to the work of Calvin”. As we said earlier, even though the King James Bible was accessible most people still continued to use the Geneva Bible.

The incongruencies in the Genesis narrative of the woman’s creation.

The creation of humanity

The book of Genesis, along with the Apocalypse, is perhaps one of the most popular narratives in Christian tradition. The reason might lay in the fact that humans are homo-narrans and as such they enjoy stories. Any story has the capacity to fill our appetite depending on how it is presented to us, however the ones that catch our attention are those destined to explore the origins of life and the ones depicting the end of it, because those two scenarios allow us to wonder what is our purpose and our place in the world.

This section focuses on pointing out some of the incongruencies presented in the biblical narrative, these trigger some questions about the interpretation given to a specific event of the Genesis: the creation of human kind, but more specifically the creation of woman and its impact on the definition of women’s status in society.

The first chapter of the Genesis presents a conflictive element in the text related to the interpretation that the Hebrew and Christian tradition have of God, in the different versions of the text the word God is used in plural form when referring to his monologues (Gen 1:26), this event, according to several scholars, is justified by the fact that God perceives himself as the Sacred Trinity during the moment of the creation. However the use of the possessive plural “our image” implies that the unicity of God is not absolute, and the creation of duality, expressed in male and female versions of his “our image”, required more than one model of the creator.

26 et ait: Faciamus hominem ad imaginem et similitudinem nostram: et præsit piscibus maris, et volatilibus cæli, et bestiis, universæque terræ, omnique reptili, quod movetur in terra.

According to Paul Heger, the term Adam is genderless and refers to Human, both man and woman were created at the same time according to the Bible text, and both were made in God’s image. God grants them equal access to all goods, gives them the same rights and trusts them the task to multiply and rule over all the inferior creatures (Gen. 1: 27-28).

27 Et creavit Deus hominem ad imaginem suam: ad imaginem Dei creavit illum, masculum et feminam creavit eos.

28 Benedixitque illis Deus, et ait: Crescite et multiplicamini, et replete terram, et subjicite eam, et dominamini piscibus maris, et volatilibus cæli, et universis animantibus, quæ moventur super terram.

Two women, two different versions?

The creation of the woman in the Bible is often associated and reduced to the creation of Eve. However the description of this event is one of the biggest incongruences of the first and second chapters of Genesis. If the events of the narrative are followed in a chronological order, one can deduce that there are two different creations of the woman in each chapter which, in Heger’s words, there are two versions coming from different sources that were amalgamated by the redactor. The events of the first chapter focus on the creation of man as species, ἄνθρωπος, and not as a singular man, ἀνδρός.

26 καὶ εἶπεν ὁ θεός ποιήσωμεν ἄνθρωπον κατ᾽ εἰκόνα ἡμετέραν καὶ καθ᾽ ὁμοίωσιν καὶ ἀρχέτωσαν τῶν ἰχθύων τῆς θαλάσσης καὶ τῶν πετεινῶν τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καὶ τῶν κτηνῶν καὶ πάσης τῆς γῆς καὶ πάντων τῶν ἑρπετῶν τῶν ἑρπόντων ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς

The second chapter of Genesis focuses on a separate creation of male and female humans, which breaks the equality of rights described in the first chapter (Gen. 1: 27-28). In this second creation, the creative process of God follows several steps, during the first step God makes the man out of dust and breathes life into him (Gen. 2: 7), secondly God assigns him a place to live and explains the rules to follow in that new place. The next step for the creation of woman is having a purpose for her and it happens in Gen 2: 22, this part of the process is preceded by an undetermined period of solitude of the first man, which makes God to consider the creation of a companion since it is not good for a man to be alone (Gen. 2:18-19). According to Heger, the interpretation of this chapter is crucial for the definition of the status of women in Christian and Jewish because it focuses not only on the creation of the woman but also on a preconception, the process of her making, and finally, the definition of her status by two facts: the declaration of her as man’s property and the definition as woman by her naming (Gen 2:23).

23 Dixitque Adam: Hoc nunc os ex ossibus meis, et caro de carne mea: hæc vocabitur Virago, quoniam de viro sumpta est.

Sources

Craig, H. (1938). The Geneva Bible as a Political Document. Pacific Historical Review, 7(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/3633847

Engammare, M. (2008). [Review of The Geneva Bible, by L. E. Berry]. Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, 70(3), 769–770. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20679944

Greenblatt, S. (2018) The rise and fall of Adam & Eve. London: Vintage.

Heger, P. (2014) “The Creation Narrative and the Status of Women.” Women in the Bible, Qumran and Early Rabbinic Literature: Their Status and Roles, Brill, 2014, pp. 11–45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76vnm.5. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Ives, E. W. “Anne Boleyn and the Early Reformation in England: The Contemporary Evidence.” The Historical Journal, vol. 37, no. 2, 1994, pp. 389–400. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2640208. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Luckyj, Christina. “Rachel Speght and the ‘Criticall Reader.’” English Literary Renaissance, vol. 36, no. 2, 2006, pp. 227–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24463757. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Shaheen, N. (1984) ‘Misconceptions about the Geneva Bible’ at Studies in Bibliography, 1984, Vol 37 (1984), pp.156-158.

Sowernam, Ester. Ester hath hang’d Haman: or an Answer to a lewd pamphlet. (1617)

Speght, Rachel. A Mouzell for Melastomus. (1617)

Swetnam, Joseph. The Arraignment of Lewd, Idle, Froward, and Unconstant Women: Or, the Vanity of Them. (1615)