Bibbia Malerbi and Rustici

Bibbia Malerbi and Rustici

by William Bonacina

The Bibles :

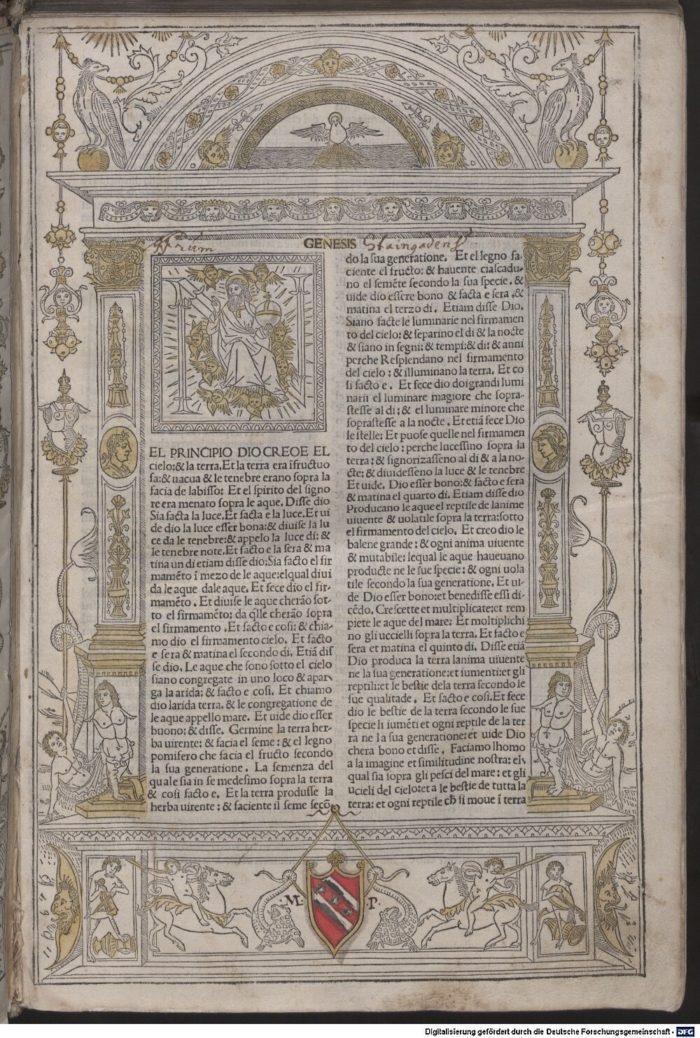

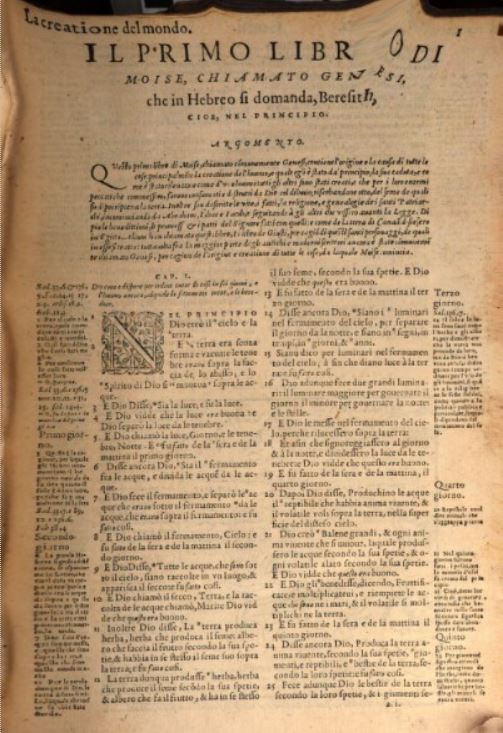

The first edition of a translation of the bible in italian was published in 1471. This translation was made by an italian monk, Nicolò Malerbi (also Malermi or Manermi). He was born in 1422 in Venice and was in the monastery of San Mattia di Murano during his work on this first integral traduction of the bible. It was probably a work that he didn’t do alone and he took some inspirations from previous partial translations, but he is still recognized as the father of this bible. The italian translation of Malerbi had a large diffusion in Italy and his bible was sold all over the peninsula, not only in Venice were it was published. Many editions of this bible appeared during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The edition that we present here is the edition of 1490, it is the first edition of this translation that has been published with illustrations included in the text. The editor Lucatonio Giunta financed this project and the printer Giovanni Ragazzo printed this new edition. We will have a look at the Genesis of this Bible with a special attention on the translation and on the illustrations. To compare the Bibbia Malerbi with another edition, we decided to have a look at the bible printed by Francesco Durone in 1562. This other italian translation is a rewrite of the Traduction of the Florentin Antonio Brucioli, who was the first to traduce the Bible in Italian from hebrew and greek in 1530, made by Flippo Rustici and printed in Geneva for a protestant use of it. We chose this other edition to put in evidence the linguistic difference and also the different types of illustrations that are used in those two versions of the holy text.

The language :

If the text translated by Malerbi is not Venetian it is sometimes far from the Florentin used as a model for Italian: it is possible to see Venetian form of talking in it. What we said is resumed by Foster in this sentence ‘it is not strictly a translation, but a revision of earlier versions to bring them closer to the Vulgate and incidentally to make their language less Tuscan and more Venetian’. If we look at the first sentences of the Genesis of the Bibbia Malermi we can see that the language used by Malerbi is not a perfect italian. For example, the word man was translated with Masculo in the first sentences of the Genesis, “Et Dio creo quello Masculo”, which is near to the latin Masculus and even more to the modern Venetian Mascolo. We also find man translated with Homo, we have sentences like “faciamo l’homo” and once again it is inspired by Venetian, today we still say Omo and not Uomo as in Fiorentin. In addition to the link with the Venetian, we can find in the text of Malerbi some latinism. For example the conjugation of the verb Fare at the third person singular is translated with facto and not fatto. If we have a look at the other translation of the bible that we choose, we can see that man is translated by Maschio and Huomo. Also, it is not Facto but Fatto. It is easily possible to see a big difference between the two translations, but if the second one is closer to Italian, the first one has a larger diffusion in Italy. The words used are really different between those two versions, because of the language used by each translator but also because they didn’t use the same version of the bible, Malerbi traduce from Latin and Brucioli from Greek and Hebrew. We are now going to see another difference between Malerbi and Rustici.

The illustrations :

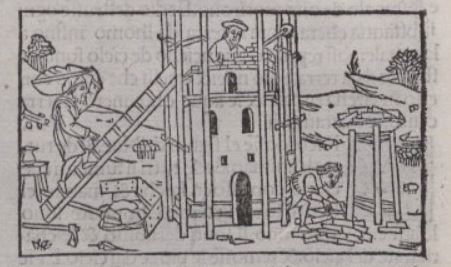

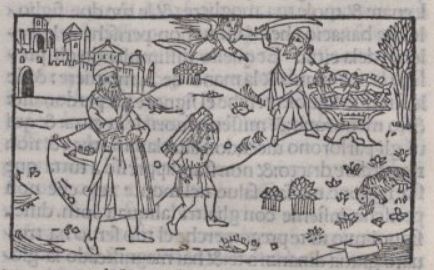

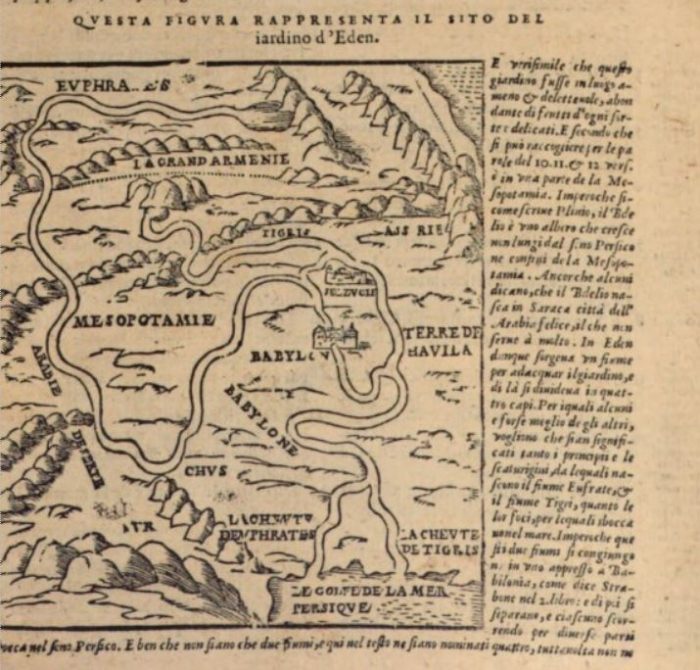

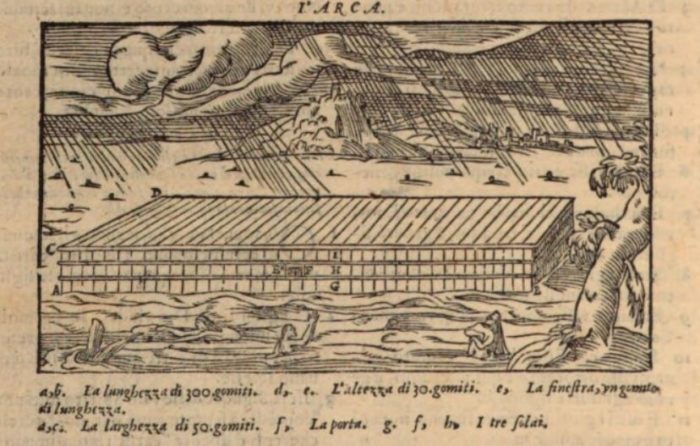

The other main difference between the two bibles that we have here is the illustrations included in the text. We will still focus on the Genesis in those two texts. In the Bibbia Malermi we can count 12 images that represent biblical scenes in the Genesis. The illustrations are simple but they give a graphical representation of the text. This translation with this kind of representation can help to understand the Bible for people that didn’t know how to read. The representations that are included in the Malerbi’s Bible are classical topos of the Genesis, they represent with simbolical illustrations the text. If we look now to the Bible of Rustici, we have a really different approach. We can find only two illustrations in this edition of the Bible but they are bigger than in the Malerbi edition of 1490. The biggest difference between the illustrations is not the size but what they represent. In the Rustici there are no biblical scenes ; We can find one map of the location of the Garden of Eden and one representation of Noah’s Ark with annotations like the size or the position of the doors. In this Bible the illustrations are more close to illustrations of technical treatises. The illustrations are less iconic than in the Malerbi’s one, the objective is not to show the scenes described in the text but to explain it as if it was an historical matter, it gives to this translation the codes of a scientific book. The explanation near the map start with “è verosimile”, the author investigate the text and expose hypothesis, once again it give to this Bible the aspect of a scholar work. Many Paratexts which explains some part of the translations that can be misunderstood are present in Rustici’s Bible and it is another difference between the two translations. This is another argument to say that this Bible is similar to a technical treatise. As this Bible is for a protestant use and as for them the text is the biggest authority in the religion, it is not surprising to have more indications for the reading in this version than in the one of Malerbi.

Sources :

http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ137109700