William Morgan’s Translation of the Holy Bible

William Morgan’s Translation of the Holy Bible

by Robert Lloyd

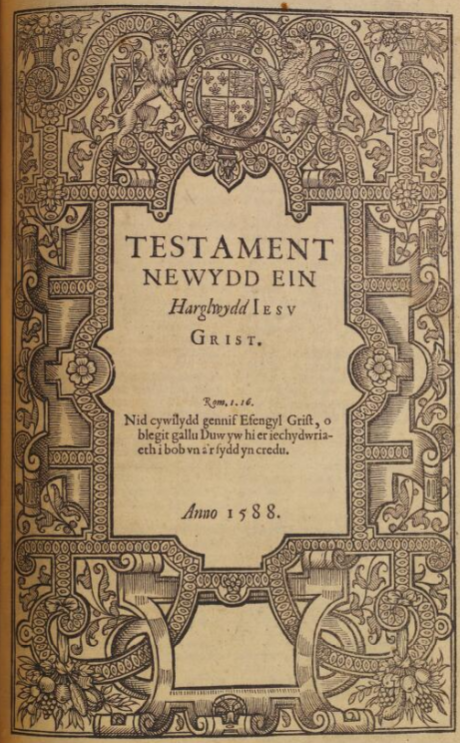

Published in 1588, Y Beibl cyssegr-lan sef Yr Hen Destament, a’r Newydd1 (The Holy Bible which is the Old Testament, and the New) was far from the first printed book in the Welsh language (Cymraeg), but with regard to its literary, linguistic, social, and political influence on Wales no other publication can boast such a legacy as William Morgan’s translation.

Using selections from the Gospels as translated by William Morgan, we’ll explore how his translation of the Bible has had dramatic consequences for Wales and the Welsh language that are relevant to this day.

| Title | Y Beibl cyssegr-lan sef Yr Hen Destament, a’r Newydd |

|---|---|

| Date | 1588 |

| Place | London, Kingdom of England; for use in Wales |

| Contributor(s) | William Morgan |

| Language(s) | Welsh (with a Latin dedication) |

| Source | National Library of Wales, 994606302419 |

| Format | [6], 436, 439-486, 488-555 leaves ; 33 cm. (2°) |

To explore the historical context of the Welsh language prior to the printing of Y Beibl cyssegr-lan, click the titles below.

The oral tradition of the Principalities of Wales (c.850)

From the earliest Welsh language sources, a culture of the Welsh-speaking aristocracy lending patronage to poets to sing of their battles and bravery is evident. Manuscripts depicting the spoken poetry of Aneirin (performing in the 6th century) are available from the 13th century, and the Red Book of Hergest – putting to parchment the words of Llywarch Hen and Heledd – appears in 1400. The Welsh language (from Old to Modern Welsh, via Early and Middle Welsh) during this period, and until the 19th century, was the vernacular of the vast majority of people in Wales.

Wales was flush with tales and traditions shared in local dialects of the language thanks to this patronage and its literary form was uniform across the Welsh-speaking world.

The Welsh language after conquest (1282)

The status of the Welsh language within the Kingdom of England has been tumultous. After eventual conquest in 1282, with the formal loss of independence enacted through the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284, those who spoke the Welsh language were subject to the displacement of their market towns to be repopulated with incoming English-speakers from the Kingdom, proscriptive laws preventing their ability to trade – or even enter – these settlements, and a limited ability to access the justice system. This was akin to what would today be regarded a linguistic apartheid2.

Annexation by the Kingdom of England (1536)

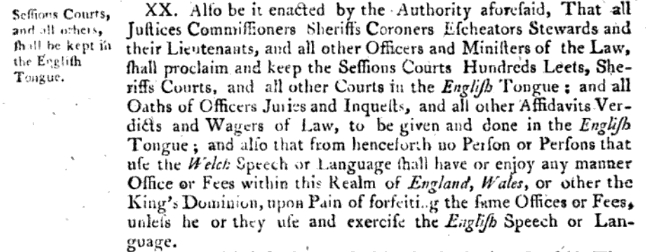

From 1536, Wales was formally annexed into the Kingdom of England through the euphemistically titled Acts of Union. People in Wales were granted equal legal status to those in England, Welsh laws that had been administered locally were disapplied and the law as set by the Parliament of England now applied to all lands and people in both countries and, with Henry VII taking the English crown with the aid of a largely Welsh army, the military occupation was finally over after some 250 years. There was, however, a condition to this equality: access to the state, including the justice system and representation in parliament, was reserved exclusively for those who spoke English.

ALSO BE IT enacted by auctoritie aforesaid that all Justices Commissioners Shireves Coroners Eschetours Stewardes and their lieutenauntes and all other officers and ministers of the lawe shall proclayme and kepe the sessions courtes hundredes letes Shireves and all other courtes in the Englisshe Tonge and all others of officers iuries enquestes and all other affidavithes verdictes and Wagers of lawe to be geven and done in the Englisshe tonge. And also that frome hensforth no personne or personnes that use the Welsshe speche or langage shall have or enjoy any maner office or fees within the Realme of Englonde Wales or other the Kinges dominions upon peyn of forfaiting the same offices or fees onles he or they use and exercise the speche or language of Englisshe.

This law3, though disapplied in practice, remained on the statute books of the United Kingdom until 1993.

This created a stark class element to the Welsh language. The gentry began, as they had under the occupation, to assimilate into the English system formally in order to take advantage of these new opportunities in public office. Meanwhile, the language that had been crafted and honed to sing the praises of princes passed from the aristocracy, through the bilingual gentry, into the “guardianship” of the largely monoglot Welsh-speaking peasantry4.

The genesis of William Morgan’s translation

As the Reformation took hold across Europe and the Church in the Kingdom of England broke away from papacy under Henry VIII, religious conformity became more important to the English state than linguistic uniformity. For people in Wales, with the vast majority being monoglot Welsh speakers, shifting from the Latin Vulgate to the English Bibles made little difference – but the threat of Catholicism spreading to Wales prompted a rush to translate the Holy Book into the vernacular of the congregation.

In 1563, a law was passed by the parliament of the Kingdom of England warranting the translation and publication of the Bible into Welsh, and in 1567 William Salesbury produced his translation of the New Testament for mass publication5.

Standardisation of Literary Welsh

A theological publication had been produced in 1546 by Sir John Prise with its own orthography of the Welsh language – which had fluctuated much in the same way the English language had until the publication of the King James Bible – and Salesbury made amendments to the orthography of the Welsh language, in part, to adhere closer to Latin. In the argument for the voiceless velar plosive (a ‘K’ sound), however, Salesbury opted for a c over the k Prise had chosen because “the printers haue not so many as the Welsh requireth“6.

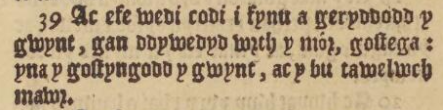

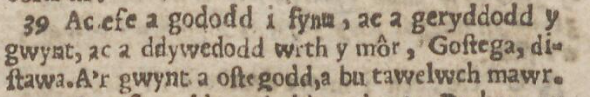

Below we can see the orthographical differences between the first printed book in Welsh and William Morgan’s Bible some forty years later. As Morgan used Salesbury’s New Testament as a point of reference, Salesbury’s orthography is preferred to that of Prise in William Morgan’s edition. As Morgan’s edition was the first widely available and sought after publication of the time, Morgan’s choices were embedded into the Welsh language itself and to this day, for example, there is no letter k in the Welsh alphabet. The existing orthography of the Welsh language was determined largely by the availability of types in English printing houses in the 16th century.

Upon the publication of Salesbury’s New Testament in Welsh, Morgan set about translating the entire Bible, using Salesbury’s translation and the few English editions available as reference, but drawing mostly from Hebrew and Greek texts. Morgan purposefully drew upon the texts uncovered in manuscripts from the 13th and 14th centuries, recounting bardic tales from the first millennium, to add a gravitas to his North Wales dialect. This edition, after all, was in-folio and designed for use only in liturgical settings.

After ten years, Morgan, assisted by Edmund Prys and the Welsh-speaking Dean of Westminster, Gabriel Goodman, completed the manuscript and headed to London to personally oversee the printing process. With publication in 1588 by an English-monoglot printer with the sole privilege to print religious texts in the Kingdom, Christopher Barker, there were many spelling errors in the final text – so many, in fact, that Morgan would spend the next decade correcting the mistakes to send again to the printers. These emendments by Morgan were never completed as Barker’s publishing house lost the manuscript Morgan had corrected. William Morgan’s death in 1604 results in the corrections being taken up by his associates Richard Parry and John Davies and published in-octavo in 16306.

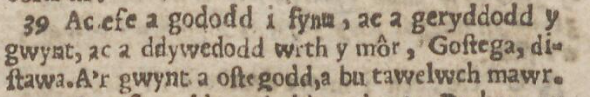

As an example of these errors, take Mark 4:39 (Marc 4:39).

Ac efe wedi codi i fynu a geryddodd y gwynt, gan ddywedyd wrth y môr, gostega : yna y gostyngodd y gwynt, ac y bu tawelwch.

Ac efe a gododd i fyny, ac a geryddodd y gwynt, ac a ddywedodd wrth y môr, Gostega, distawa. A’r gwynt a ostegodd, a bu tawelwch mawr.

Here we can see some substantial revisions between the original 1588 edition of William Morgan’s Bible, but to focus on spelling over grammar, note the spelling of the word ddywedodd (he said). In the revised edition, the modern Welsh spelling of 1630 ‘-dodd‘ corrects the original edition’s error of ‘-dyd‘.

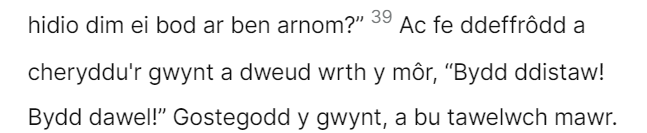

The revised edition became the first mass-produced book printed in Welsh for use by individuals at home and this cemented Morgan’s translation as the archetype for what will become literary Welsh – using phraseology largely redundant in spoken Welsh but still used in literature (much like the passé simple tense in French). We’ll take the same example from Mark 4:39 (Marc 4:39) as above, but this time pay attention to the grammar over the spelling.

Ac efe a gododd i fyny, ac a geryddodd y gwynt, ac a ddywedodd wrth y môr, Gostega, distawa. A’r gwynt a ostegodd, a bu tawelwch mawr.

Ac fe ddeffrôdd a cheryddu’r gwynt a dweud wrth y môr, “Bydd ddistaw! Bydd dawel!” Gostegodd y gwynt, a bu tawelwch mawr.

Translation:

And he woke up and rebuked the wind and said to the sea, “Be still! Be quiet!” The wind subsided, and there was a great calm.

The pronoun efe is only present in literary Welsh and is used to emphasise that he (in this instance Jesus) – is doing something. In spoken Welsh (used in the Beibl Cymraeg Newydd Diwygiedig, attempting to make the text of the Bible more accessible) the word fe performs the same, if less dramatic, function in the modern revised edition7. Similarly, in spoken Welsh, the verbal noun dweud performs the function (to-infinitive) to indicate Jesus said something to the sea (wrth y môr), but in literary Welsh, this function is performed by the third-person singular preterite (passé simple) conjugation of the verbal noun – conjugating dweud to dywedodd (with a soft mutation of d (d) to dd (ð) because of the vowel prior).

Legacy of the William Morgan Bible

Alongside standardisation due to the mass production and accessibility of the 1630 revision in-octavo, for the first time, households could have the word of God in their own home for them to study and talk about independently. Morgan’s Bible was used by traveling schools in Wales in the 18th and 19th centuries, resulting in a boom in literacy in Wales, too, resulting in Wales becoming one of the first majority-literate nations in Western Europe.

Although the language was again castigated in the 19th century for being ‘parochial‘ and ‘immoral‘8, despite thousands of titles being produced in Welsh until the first English-language book in 1727, the mass production and use of this first complete Bible in the vernacular did enough to undo the Welsh language’s tumultuous beginnings in the English, and subsequently British, state.

While the Welsh language continued to be the majority language of Wales until the 20th century, the role William Morgan’s Bible played in nurturing a Welsh national identity and protecting a language and culture is immutable. Wales remains the only nation within the United Kingdom without a state church, due to the rise in nonconformist, explicitly Welsh evangelicalism that spread with his translation.

That is why no other book in the Welsh language can boast such a legacy as William Morgan’s 1588 complete translation of the Bible.

References

- Morgan, W (1588). Y Beibl cyssegr-lan sef yr Hen Destament, a’r Newydd. London: Christopher Barker. Available at: https://viewer.library.wales/4701320#?xywh=-1116%2C-1%2C4774%2C4008&cv=885 ↩︎

- Johnes, M. (2019). Wales: England’s Colony. Parthian Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3888959/wales-englands-colony-pdf ↩︎

- Raithby, J (1811). The Statutes At Large, of England and of Great-Britain: From Magna Carta to the Union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, 1660-1707, Vol 3, London: Eyre & Strahan, p252. ↩︎

- Davies, J. (2014) The Welsh Language. 1st edn. University of Wales Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/573132/the-welsh-language-a-history-pdf ↩︎

- Salesbury, W (1567). Testament Newydd ein Arglwydd Iesu Christ gwedy ei dynnu… London: Henry Denham. Available at: https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/printed-material/william-salesburys-new-testament ↩︎

- Morgan, W; Parry, R; Davies, J (1630). Y Beibl cyssegr-lan sef yr Hen Destament, a’r Newydd. London: Robert Barker. Available at: https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/europeana-rise-of-literacy/religious-publications/y-bibl-cyssegr-lan-sef-yr-hen-destament-ar-newydd ↩︎

- British & Foreign Bible Society (2004). Beibl Cymraeg Newydd Diwygiedig. British & Foreign Bible Society [website]. Available at: https://www.bible.com/bible/394/MRK.4.BCND ↩︎

- National Library of Wales (2023). The Blue Books of 1847. National Library of Wales [website]. Available at: https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/printed-material/the-blue-books-of-1847 ↩︎