Bible d’Olivétan

Bible d’Olivétan

by Jérémy Ducret

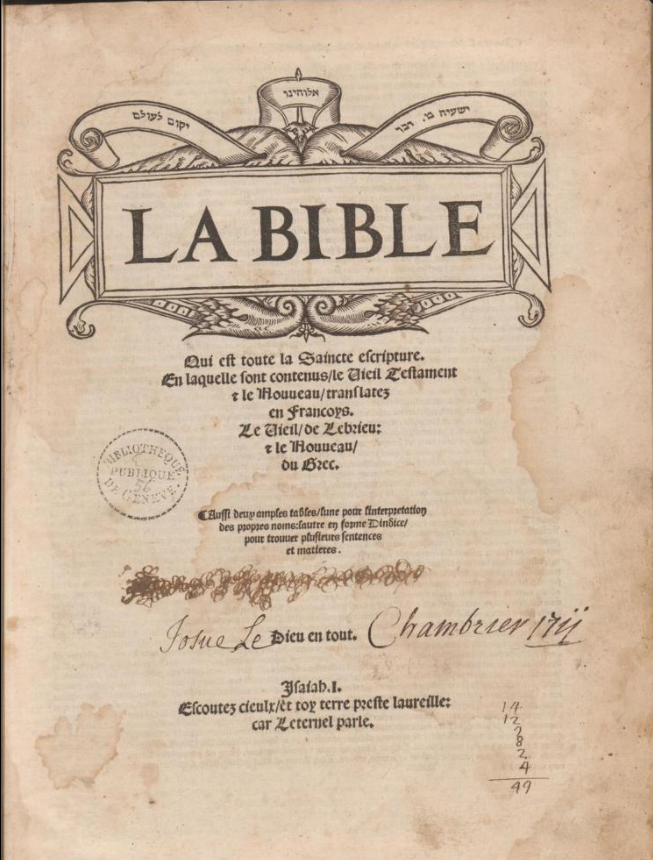

- Author: Pierre Robert Olivétan

- Title: Bible d’Olivétan, Bible des Vaudois, Bible des martyrs

- Date: 1535

- Edition: Original edition of 1535

- Editor: Pierre de Vingle, Neuchâtel

- Pages: 851

- Language : French

- Source : Bible d’Olivétan, Internet Archive

Purpose

This Bible is a translation by Pierre Robert Olivétan (1506-1538). Olivétan was a cousin of Jean Calvin, the famous French humanist. This edition is the first Protestant translation of the Bible, based on the Erasmus text and the Massoretic Hebrew text. It was published in 1535 par Pierre de Vingle in Neuchâtel. This is the first Bible made with the originals texts.

Olivétan was born in 1506 and died in 1538. He was an erudite man who knew how to handle the art of letters. Indeed, he was able to use four languages: Latin, Hebrew, Greek and French. Let us remember that at that time, Greek and Latin were the major languages for all scholars. He was a discreet man who used many nicknames in order to escape certain convictions. Indeed, because of his ideologies, or even here because of his Protestant translation, he took many risks and could put himself in danger. He is thus known by various names such as Pierre Robert, or simply Olivétan. He also uses the following nickname: “Belisem de Belimakom”, the one with no name and no place. His translation of the Bible will bear his name.

Formal aspects

The title page offers few information. Indeed, we can only observe that it is a translation of the New and Old Testaments of the Bible. The New was translated from the Greek, and the Old from the Hebrew text. It also informs us of the presence of two tables: one offering proper names and the other is a table of contents. Immediately after the title page, we see the privileges, a page written in Latin. Then we find the apology of the translator. After the introductory texts, the Bible begins with the Old Testament, followed by the different books of prophecy.

Then we find the apocryphal texts, which are here translated by the common translation because the Greek and Hebrew texts are not found. The Bible ends with the New Testament texts and a table of contents. From a typographic point of view, Olivétan produces some elements to highlight certain aspects and words. For example, as mentioned in La Bible d’Olivétan, A propos du colloque de Noyon1, “Olivétan intends to distinguish between words that have their equivalent in the translated text and those that are added […] he has printed those in smaller type.” The author leaves nothing to chance in his bible and wants to guide the reader through the reading.

Of course, the language chosen by Olivétan is important. Indeed, he decided to offer the Bible in French and thus increase his audience. He reached out to the people and this aimed to promote Protestantism and increase the sales of his Bible. However, sales of the Bible will be low.

Political Value

This Bible was published in 1535, in a complicated historical context. This was shortly before the beginning of the wars between Catholics and Protestants. In 1534, on the night of 17-18 October, a Protestant manifesto against the mass was posted in various places in France, one of which was at the king’s own door in Blois. This was the “affaire des placards” and the beginning of the persecutions against the Protestants. Shortly after this case, a protestant was burned. The 13th of January represents the creation of the “chambre ardente”, which was set up to hunt down protestants. This court will later be used to settle problems concerning attacks on the French state. Here, a royal edict was issued to censor printers and close bookshops. This is the first act of censorship since the creation of printing.

In 1535, Francis the Ist had six protestants burned. It is this kind of act that will make the protestants want to make their own bible to continue to oppose Christianity.

Ten years later, the king had 3000 Vaudois executed in the Luberon mountains. It was a real genocide, nearly twenty villages were totally destroyed. It seems that in his last days, Francis the Ist strongly regretted this action.

It is thanks to this kind of event that this bible will be known to have many nicknames. Indeed, it is called “Bible d’Olivétan” in relation to its author, but also “Bible des Vaudois”. It will take this name in relation of two things. First of all, it is necessary to say that it is thanks to the Vaudois that this Bible was born. Indeed, they wanted to create a Protestant Bible and so they called on Olivétan, through Jean Calvin, to be the translator. The Bible will definitely take this nickname after the massacre mentioned above.

The Vaudois represented a community that dates back to the 12th century. They belong to the Vaudois evangelical church established by Pierre Valdo alias Vaudès, a merchant from Lyon, born in 1140 and who died in 1217. He was one of the first to produce a Bible in the vernacular. The cult that he put forward was poverty, and he set up the movement “the poor of Lyon”.

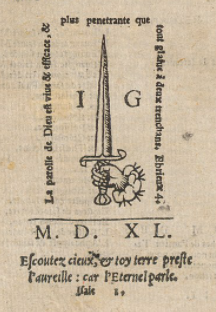

The Bible will also be called the Martyrs’ Bible, also in reference to the Vaudois genocide. The fourth famous name of this Bible will be the Sword Bible. It was so named because in 1540 a revised edition appeared with a sword on the title page, a typographical mark of the printer.

Transcription

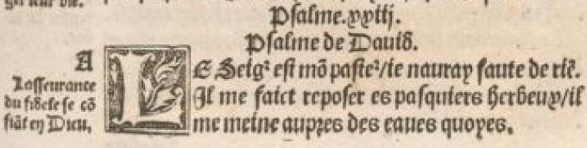

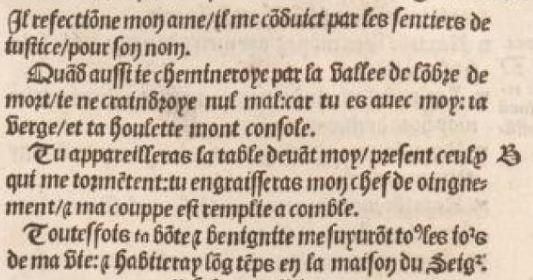

Psaume 23, David

Le Seig[neur] est mô paste[ur]/ je nauray faute de rie[n].

Il me faict reposer en pasquiers herbeuy/il

me meine aupres des eaues quoyes.

Il refectione mon ame/il me coduict par les sentiers de

justice/pour son nom.

Quad aussi je chemineroye par la balle de lôbre de

mort/je ne craindroye nul mal: car tu es avec moy: ta berge/et ta houlette mont console.

Tu appareilleras la table deuat moy/present ceusy

qui me tormêtent: tu engraisseras mon chef de oignement/

a ma couppe est remplie a comble.

Touteffois ta bote a benignite me suyurôt to° les io(jours)

de ma bie: a habiteray lôg têps en la maison du Seig[neur].

Contemporary version

Psalm 23, David2

L’Eternel est mon berger: je ne manque de rien.

Il me fait reposer dans de verts pâturages,

Il me dirige près des eaux paisibles.

Il restaure mon âme,

Il me conduit dans les sentiers de la vie juste,

A cause de son nom.

Quand je marche dans la vallée de l’ombre de la mort,

Je ne crains aucun mal, car tu es avec moi :

Ta houlette et ton bâton me rassurent.

Tu dresses devant moi une table,

En face de mes adversaires;

Tu oins d’huile ma tête,

Et ma coupe déborde.

Oui, le bonheur et la grâce m’accompagnent

Tous les jours de ma vie,

Et je reviendrai, j’habiterai dans la maison de l’Eternel

Jusqu’à la fin de mes jours.

The Psalm

There is a huge difference between the two psalms. Indeed, the one in the Olivetan Bible is not easy to understand, even for a french. Of course, this is understandable because the french language has evolved so much. Moreover, the words are largely abbreviated. This is probably due to a concern for space.

We have attached a representation of David3 as a musician. It is a statue which is in France, in Tressignaux in Brittany, in the chapel of Saint-Antoine. Unlike our Bible, this is a Christian representation of David, but it is always interesting to see how a biblical character was represented at that time. Indeed, this statue was made in the 16th century, it is made of polychrome wood and measures 66 centimetres.

Bibliography

- La Bible d’Olivétan. A propos du colloque de Noyon (mai 1985).

- Psaume 23 “L’Eternel est mon berger, je ne manque de rien”, Oratoire du Louvre.

- Ministère de la Culture.