The Bible of Sacy

« The Bible of Sacy »

by Johanna Saadoune

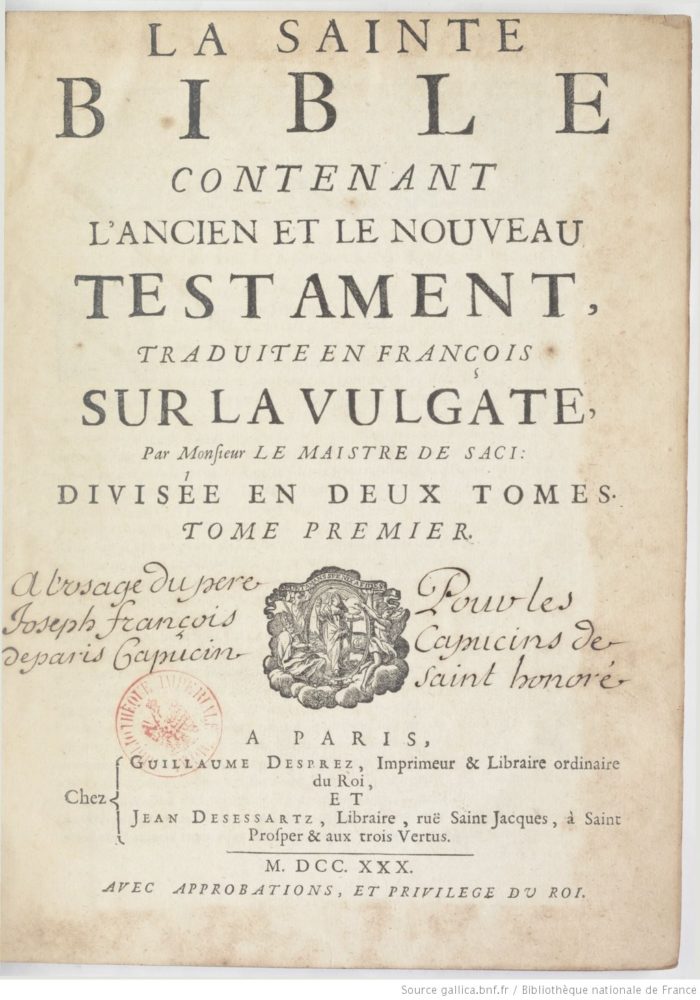

- Author: Le Maistre de Sacy, Isaac-Louis (1613-1684)

- Title: La Sainte Bible contenant l’Ancien et le Nouveau Testament, traduite en franc̜ois sur la Vulgate. Tome 1 / , par monsieur Le Maistre de Saci

- Date: 1730

- Editor: Paris, chez Guillaume Desprez et Jean Desessartz.

- Pages: 935

- Language : French

- Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Purpose

The “Bible de Port Royal” concerns all of the translated Bible in French which were published by the Messieurs de Port Royal between 1665 and 1696. Numerous publications of the complete Bible in several volumes were edited with explanations and commentaries. They are called “grandes explications” or “notes courtes”. This French translation is called “La Sainte Bible contenant l’Ancien et le Nouveau Testament”. Besides, it is famous under the name of “Bible of Sacy” from the name of Louis-Isaac Lemaistre de Sacy, who was the leader of the project.

As it is described in the work of Geneviève Delassault, Le Maistre de Sacy et son temps (1957), Sacy spent the last five years of his life working on the translation of the Ancient Testament. In the Avertissement part at the very beginning of the book can be seen his beliefs: « Mais surtout il y a une au commencement du livre de la Genèse , qui renferme les plus fortes preuves dont Saint Au-gustin s’est servi dans ses écrits, pour appuyer d’une part l’autorité toute divine des Écritures, & pour établir de l’autre par ces mêmes Écritures, la vérité de la Religion de Jésus-Christ » (page v). Indeed, this sentence shows without any doubt the recognition of the influence of the Saint. It is also a message to justify the approach for the work. Sacy wanted to claim in this translation his faith in the sacred texts to be the only behavior code in this world.

Formal aspects

This edition is a in-quatro format. It also contains a table of content.

In the very beginning of the book, the Avertissement part aims at giving concrete explanations about the intentions of the edition. As says the Dictionnaire encyclopédique du livre, the Avertissement « implique l’impuissance du texte à se présenter lui-même ». It is an external text apart from the book, its purpose is to intro-duce the work, to give a context, in order to justify it. The author tends to persuade the reader by influencing and guiding their thoughts. As a consequence, one can assume it was written by the associated partners who printed and sold it.

Moreover, one of the value of the edition is to have an Appendix. The latter contains « L’Explication des noms Hebreux, Chaldéens & Grecs », « La Chronologie Sacrée », « La Table des Matieres » and « La Table des Epîters & Evangiles de toute l’année ». It definitely confirms the will to enlighten the believer while they would browse the book.

Political value

The Bible of Sacy was conceptualised in a tumultuous political context. Under the reign of Louis XIV, France knew different troubled periods. Among them, one can count the Fronde, a period marked by a brutal reaction against the rise of monarchic authority which started under the reign of Henri IV and Louis XIII. There are several factors that could explain the revolts. First, they are of social order: the privileges of Parisians parliamentarians put in question. In terms of fiscality, one could accuse the increasing pressure of the taxes. Then politically speaking, the will of the royal power to govern by its own in an absolute monarchy.

Sacy published his Office de l’Église, a translation of hymns freely interpreted according to the Augustan theology of Salvation and Grace. The work receives a positive welcome by intellectuals, such as Corneille, Racine and La Fontaine. However, the Jesuits condemn the book and the latter was put at the Index by Rome in 1651.

The author was often accused of being influenced a lot by the Jansenism ideas. Cornelius Jansen, was a bishop of Ypres (1585-1638). He was an important supporter for the full Augustinism against the Jesuits. His full thought contained in his life work Augustinus (1640) influenced so much the movement it took his name.

The following years kept with the religious debates under the royal power making pressure. Still, the churchman published another work which met a lot of success. It even led for Sacy to be taken to the Bastille for a stay as he was standing his positions against the other theologians.

Transcription

PSEAUME XXII.

Pfeaume de David.

David dans ce cantique compare Dieu à

un Pafteur qui a foin de fes brebis, qui

les conduit dans de gras pâturages, &

les tient à l’abri des infultes du loup : &

le remercie de lui avoir procuré la paix,

& de l’avoir protegé contre fes ennemis,

& déclare qu’il a mis en lui toute fa

confiance.

I. C’Eft le Seigneur qui me conduit ; rien

ne pourra me manquer : il m’a établi

dans un lieu abondant en pâturages.

2. Il m’a élevé près d’une eau fortifiante ;

& il a fait revenir mon ame.

3. Il m’a conduit par les fentiers de la jufti-

ce, pour la gloire de fon nom.

4. Car quand même je marcherois au mi-

lieu de l’ombre de la mort, je ne craindrai

aucuns maux, parceque vous êtes avec moi.

5. Votre verge & votre bâton ont été le

fujet d’une grande confolation pour moi.

6. Vous avez préparé une table devant

moi contre ceux qui me perfecutent.

7. Vous avez iot ma tête avec une huile

de parfum. Que mon calice qui a la force

d’enivrer, eft admirable !

8. Et votre mifericorde me fuivra dans

tous les jours de ma vie.

9. Afin que j’habite très-long-tems dans

la maifon du Seigneur.

Contemporary version of the Psalm

« 1L’Éternel est mon berger : je ne manquerai de rien.

2Il me fait prendre du repos dans les pâturages bien verts, il me dirige près d’une eau paisible.

3Il me redonne des forces, il me conduit dans les sentiers de la justice à cause de son nom.

4Même quand je marche dans la sombre vallée de la mort, je ne doute aucun mal car tu es avec moi.

Ta conduite et ton appui : voilà ce qui me réconforte.

5Tu dresses une table devant moi, en face de mes adversaires ; tu verses de l’huile sur ma tête

et tu fais déborder ma coupe.

6Oui, le bonheur et la grâce m’accompagneront tous les jours de ma vie et je reviendrai dans

la maison de l’Éternel jusqu’à la fin de mes jours. »

Bible Society of Geneva, 16th edition, 2014.

Comparison of the two versions of the Psalm

The first part of the text in italic does not seem to belong to the Psalm it-self. It could explain why it was printed in different typographies. There are characters looking like manuscript ones. The paratext is here to explain the Psalm and thus has a didactic purpose for the reader.

In the third and seventh verses, the words “la gloire” and “de parfums” are also in italic with manuscript typefaces. Different elements might think these words do not belong to the original text. Indeed, the typography employed is the same as in both paratext and Avertisement. On the contrary, one can see that when a saint is quoted, the font remains classical and not in italic.

Nowadays, the psalm of « Le Seigneur est mon berger… » is a bit different from the version of the Bible of Sacy. Still, the meaning remains the same. Firstly, in the 1730 Bible, the Psalm is numbered as the 22nd and not as the 23rd. There are more verses in the 18th century edition than in the recent one. On the contrary, the latter have a more complex grammatical construction and are longer. One can say with the example of the Psalm, the Bible of Sacy was built to be simple for the comprehension but rich in its language.

Value given to the edition

In some way, one might notice the paradox between several condemned published works which were both still supported and claimed. Although the monarchy was repressing divergent religious ideas, it seems it remained a form of liberty of production. As the political context was already explosive, one might advance perhaps it could have been worse to forbid for once and all the publications ? In the end of his reign, Louis XIV wanted to obtain from the pope an official condemnation of the jansenist ideas. He obtains from hims the Unigenitus bull which condemns 101 propositions from the Nouveau Testament avec des réflexions morales […] written by P. Quesnel, a figure of the movement. However, the condemnation of four bishops and the death of the cardinal de Noailles in 1729 both mark the end of the episcopal jansenism.

Nevertheless, an element on the title page of the Bible shows its final acceptance. One can see the words “A l’usage du pere Joseph François de Paris capucin. Pour les capucins de Saint Honoré.” Indeed, the use of this edition by monks from the order of the capuchins proves its legitimacy according to the Catholics.

The Catholic Church has been remaining reserved about the topic of reading the Bible. After the council of Vatican II, the attitude of the institution deeply changed. And so did the look on the work of the intellectuals of Port Royal. The author Bernard Chédozeau wrote in his essay that the originality of the augustan movement had a double aspect. The one to offer both « une approche riche et en même temps simple de la Bible ». Even though it was first condemned for that, the Church would take two centuries to evolve.

Bibliography

Bogaert Pierre-Maurice. Bernard Chédozeau, Port-Royal et la Bible. Un siècle d’or de la Bible en France. Préface de Philippe Sellier, 2007. In: Revue théologique de Louvain, 42ᵉ année, fasc. 2, 2011. pp. 265-268. www.persee.fr/doc/thlou_0080-2654_2011_num_42_2_3932_t5_0265_0000_1

Chédozeau Bernard. Quelques remarques sur la traduction des textes sacrés catholiques aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. In: Littératures classiques, n°13, octobre 1990. La traduction au XVIIe siècle. pp. 197-207. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/licla.1990.2662 www.persee.fr/doc/licla_0992-5279_1990_num_13_1_2662

Flament Pierre. G. Delassault. Le Maistre de Sacy et son temps. In: Revue de l’histoire des religions, tome 154, n°1, 1958. pp. 113-114. https://www.persee.fr/doc/rhr_0035-1423_1958_num_154_1_8840

Muntéano Basil. Port-Royal et la stylistique de la traduction. In: Cahiers de l’Association internationale des études francaises, 1956, n°8. pp. 151-172; doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/caief.1956.2091 https://www.persee.fr/doc/caief_0571-5865_1956_num_8_1_2091

Sitography

Camille Rouxpetel. “La Bible de Port-Royal”, Élisabeth VUILLEMIN (Université Lyon-2). Hypotheses. Publié le 28/08/2018. [consulté le 10/10/2021]. Accessible sur : https://normesrel.hypotheses.org/699