Codex Gigas

Codex Gigas – The Devil’s Bible

By Jordyn Anable

The Codex

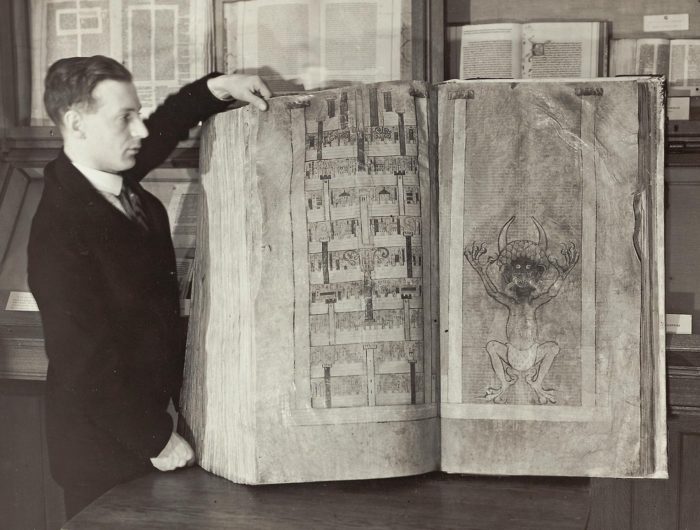

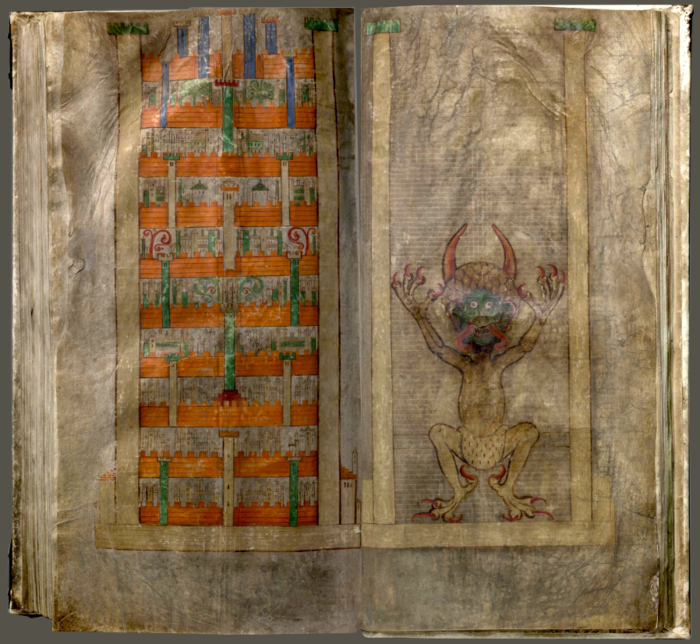

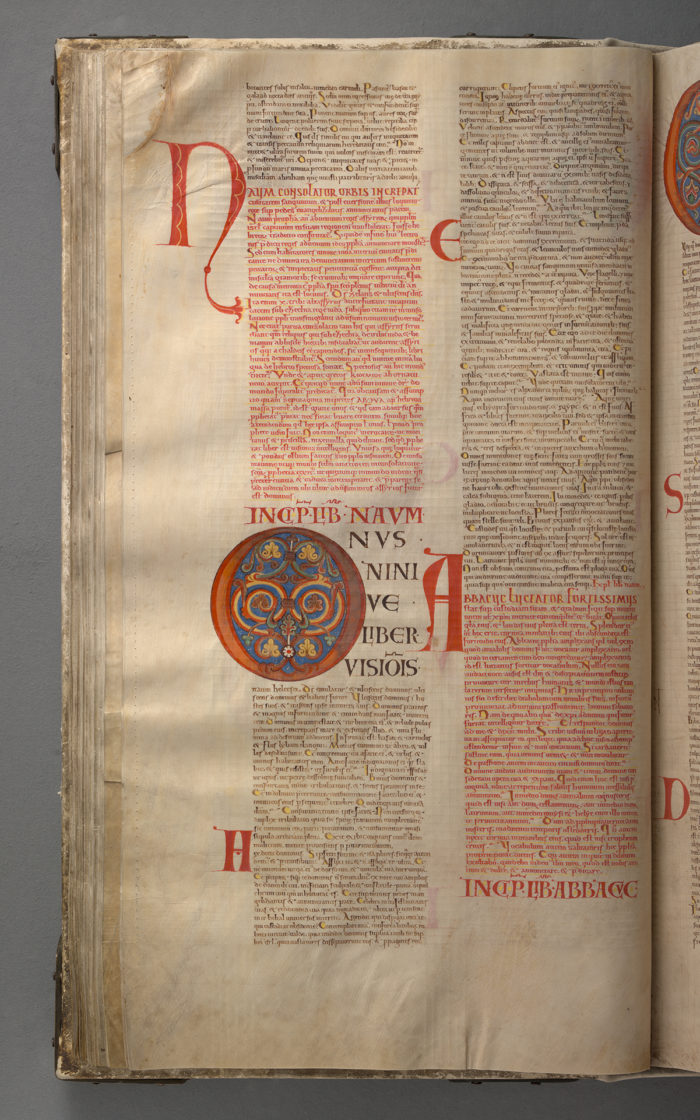

The Codex Gigas, or The Devil’s Bible as it is known in English, is a medieval manuscript written sometime in the early 13th century from Bohemia. It contains the Old and New Testament and five other works in addition to a full-page illustration of the Devil (pictured below), for which the book is named. It has had several permanent homes, but today resides in the National Library of Sweden.

Physical Description

| Title | Codex Gigas (The Devil’s Bible) |

|---|---|

| Contributor(s) | Unknown; Josephus, Flavius (c.36-100); Isadore, of Seville, Saint (636) |

| Date | 1204-1230 |

| Place | Bohemia, Czech Republic |

| Format | 49x89cm, in folio |

| Language(s) | Latin |

| Source | World Digital Library – Library of Congress |

The codex is the largest preserved medieval manuscript believed to exist today. It weighs 75 kilograms and contains 310 sheets of parchment. Its current binding is an ornately embossed white leather with intricate metal corners covering wooden boards. It was manufactured in 1819, while the wooden boards underneath are likely still part of the original binding.

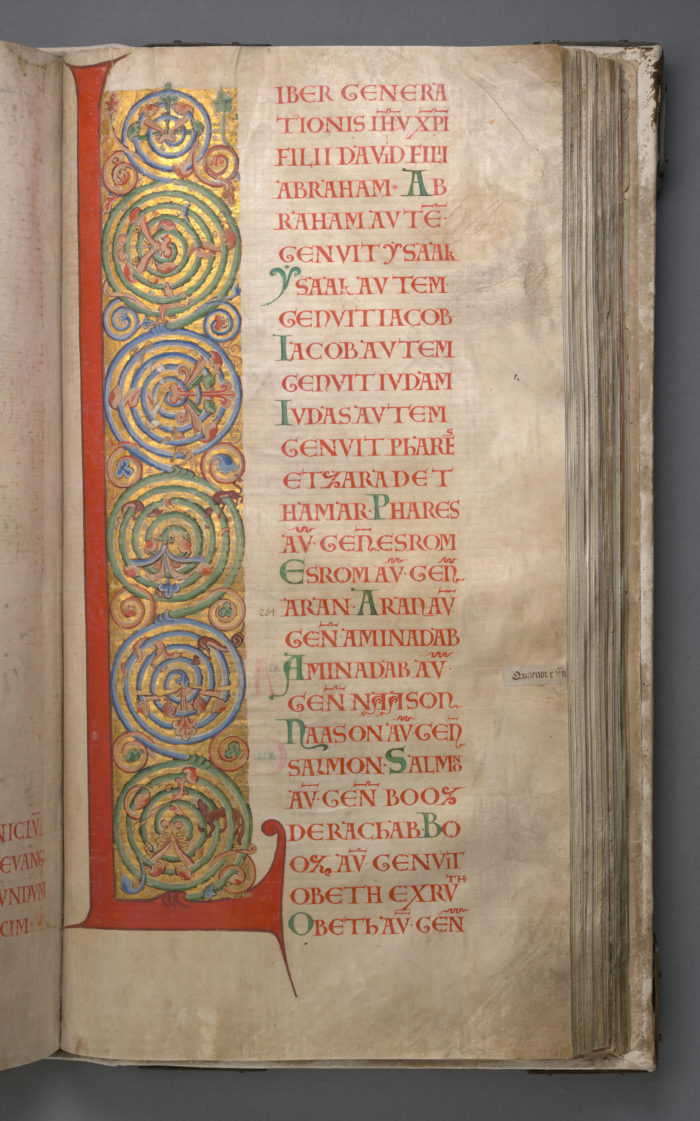

Inside, it has a total of five pictures; the two full page ones displayed above, three in the margins and 77 decorated initials. Six of these initials are full page illustrations including animal and plant motifs while the remaining ones are smaller with more abstract and geometric decoration.

Given the age of the book, it is in very good condition. However, there are areas with serious and distinct damage. The first several pages are missing, with the book beginning at the flood and Noah in Genesis. There is also an entire work, The Holy Rule of Saint Benedict, which was removed. For majority of the book, the parchment is in very good condition and the writing is still clear and legible. The only exceptions are the the first page of the book, where there is significant aging and distortion and the images of the Devil and the Kingdom of Heaven, where they were presumably damaged by light while on display.

Books in the Codex

The Codex itself is composed of many texts. The first half is made up of the Old and New Testaments, while the second half contains five long texts and a few short texts.

The five long texts are comprised of two texts by Josephus Flavius (c. 37-100 CE), Antiquities of the Jews and The Jewish War, Isadore of Seville’s (c. 560-636 CE) Etymologiae, and two authorless compilations, the Ars Medicinae and the Bohemian Chronicle of the Cosmas of Prague(c. 1100). The Antiquities of the Jews describes the history of the Jewish people until 66 CE, and The Jewish War tells the story of the Jewish rebellion against the Romans in 66-70 CE. The Etymologiae is a medieval encyclopedia which provides an introduction to classical knowledge, instruction for new Christians and explain how the ancient world transitioned into the Roman Catholic Church. These three works were historical and instructive, but based on topics specifically relating to Christian and church history. These and the Ars Medicinae – an introduction to medicinal science and diagnostic texts, made up mostly of the Aphorisms of Hippocrates – were general knowledge books, that any literate person in medieval Europe would have been familiar with. The last book is much more regionally specific and is the first written history of Bohemia. This specific copy remains an important source for Czech historiography.

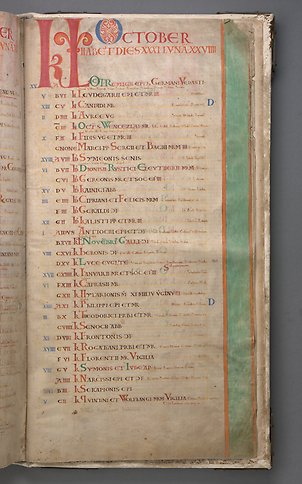

The short texts are more varied. They include a confession of sins, a calendar, and magical spells. The confession and spells both are added near the illustration of the Devil. The confession is written by a man of the church and ends with a prayer for forgiveness and mercy before then showing the illustration. It perhaps is meant to remind the reader of promise of Heaven and to encourage them to repent. The spells are to cure disease and fever, and rituals to capture thieves. Because the spells appear after the image of the devil, it is postulated that they were included to ward off any negative effects the depiction of the Devil may bring the viewer. The rituals to capture thieves would have been a level of protection for such a valuable book. The calendar includes a list of saints’ days to celebrate and a list of the death dates of Bohemians who were both clergy and laypeople.

A History of the Codex

We do not know precisely where or when the Codex was produced. However, due to the consistency of the script it is very likely that the book was written by a single scribe, over the course of twenty to thirty years. While we do not have a specific date for when the book was completed, it was likely completed at some point between 1223 and 1230 CE. While the official range extends to 1204 CE because of the inclusion of Saint Prokop (canonized in 1204), a Prague bishop who died in 1223 is included in the list of significant death dates. The later range was determined through the absence of King Ottokar I of Bohemia, who died in 1230 and would have been included in the necrology if he had passed before the book was completed.

The first official date we have for the book is in a note on the inside of the front cover. The note is a pledge from monks in Podlažice, loaning the codex to a monastery in Sedlec in 1295. In that same year it was purchased by the Benedictine Order of Břevno Monastery. It remained in the monastery, as a draw for travelers to visit until 1594 when Emperor Rudolf II visited the monastery. His interest in collecting oddities and occult items was well known; he decided to borrow the book permanently and moved it into the Hapsburg collection in Prague.

In 1648, at the end of the Thirty Years’ War, a group of Swedish soldiers looted the city. More than three thousand men searched the city, their looting guided by a list of valuables owned by the Hapsburgs. The codex and a large number of other books were included on that list. Once in Sweden, the book was brought to the library at the Royal Palace in Stockholm. It was transferred to the National library in 1878. Today it has been digitized and the physical book is on display in their treasury room.

The Role of the Book

The size of this book makes it immediately clear that it was meant to be more than a simple compendium of texts. Within a century of its creation, it was famous across Bohemia and has inspired several legends about its creation. The degradation of the images of the Devil and Heaven clearly show that it was often held open to display them, causing the light damage. However, it was not only a symbolic book to put on display, as there are marginalia, notes from several people indicating the long term usage of the book.

The size, initial location, and content of the book can tell us a bit about what its original purpose was. It was large enough to immediately be an impressive and imposing tome. But at the same time the size was necessary to contain all of the texts in a single volume. The script is quite small, with letters between 2.5 to 3 millimeters tall and divided into two columns. The Chronicle of the Cosmas is typically 200 pages long, but it only takes 11 pages in the Codex to recount.

The texts form a corpus, a canon, for the spiritual and intellectual life of a Bohemian, likely the clergy and monks because of its placement in the monastery. It starts with the Bible because that was the center and most important aspect of one’s life. The next three works are histories of Judaism and Christianity, important foundational works that any man of good standing should know. There is then the medicinal work, so that one could better understand their own and others’ ailments and bodies. The last of the long works concludes with the history of Bohemia, giving the national identity importance (but not superseding the place of the Church and Christianity). The confession, the magic, and the calendar are all important pieces of information, once again emphasizing Christian practice. It would have been a guide, so that one could know what they should know and what others should know as well. It would also function as a reference work, as it contained so many works and pieces of information all together in one place in neat, clear script. The calendar and the necrology are the clearest examples, where the important saints and people were clearly listed and easily found, as they exist at the end of the book.

However, its illumination would influence its role and significance in later eras. The large and grotesque image would captivate Rudolf II and inspire countless legends of a monk possessed by the Devil creating the book in a single night or people going crazy and falling ill suddenly after spending too long with it. Its size and construction continued to inspire, and the rebinding (while likely necessary) only contributed to the impressiveness of its stature. The occult fascination continues today, with the English moniker directly inspired by the image of the Devil and much of the modern cultural discussion of the book focusing on occultism and the image.

Genesis 22:1-19

The Sacrifice and the Codex

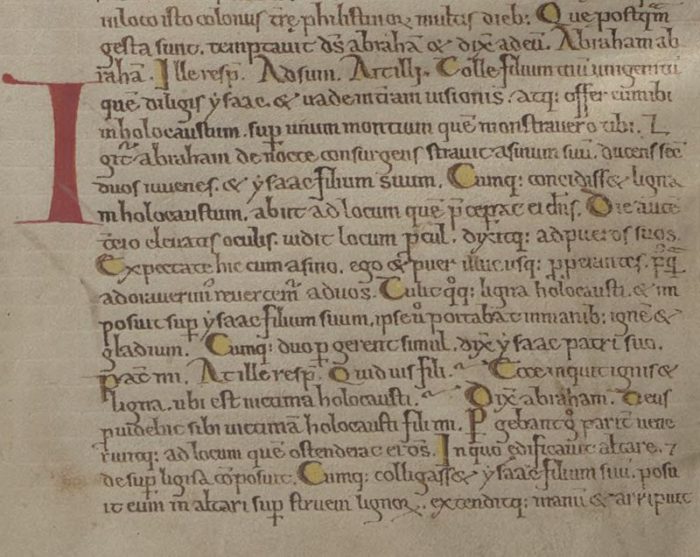

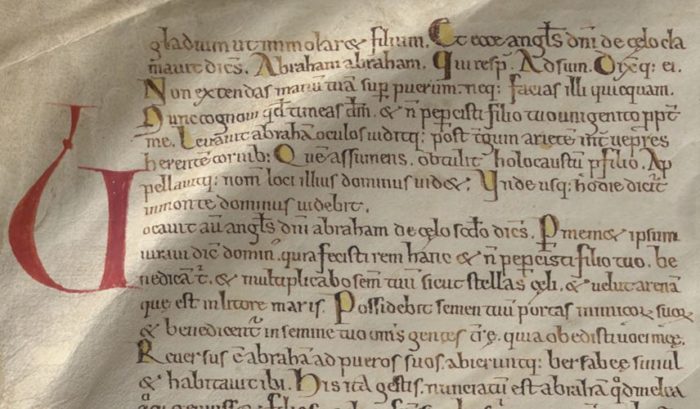

The passage in the codex takes up only a small section and has little identifying the traditional start and end of the story. The two capitalized letters do not correspond with the start of the chapter and, while the beginning of the book has it, there are no marginalia indicating where the story begins. The text itself has the standard manuscript contractions and does not deviate from the Vulgate.

Genesis 22:1-19 is the section of Genesis that is typically called, in the Christian tradition, The Sacrifice of Isaac. It is God’s test of Abraham, commanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac, and as Abraham proves his loyalty, God spares the boy and blesses Abraham and his descendants. This translation used specifically and only from the Vulgate text of the manuscript. It bears a close resemblance to the Douay-Rheims version (which can be seen below). The other two English translations included differ somewhat significantly from the Vulgate text, because they were more influenced by the Greek and Hebrew sources.

The Binding and Medieval Jewish Art

While the Codex is a Christian work, steeped in Christian traditions, the story of Abraham and Isaac is not contained to Christianity. Even in the Codex, Judaism’s presence echoes in the work of Josephus Flavius. In Prague and the surrounding areas there were Jewish communities, though in the centuries after the creation of the Codex they would see a drastic increase in persecution, with increased taxes, property seizure and societal bigotry forcing large communities out.

The passage Gen 22:1-19 is known as The Sacrifice of Isaac in the Christian tradition; in the Jewish tradition it is called The Binding of Isaac. The events in the passage are the subject of a prayer for the second day of Rosh Hashanah, the subject of many commentaries and referenced in a lot of liturgical poetry.

Jewish religious art in Medieval Europe was contained mostly to manuscript illuminations. While there are paintings in synagogues in the Middle East that date from the second and third centuries AD, either medieval European synagogues did not survive or were not decorated in this manner. Due to the importance of the binding in Judaism, there are many examples of this scene in medieval Jewish books.

Much of the medieval art was produced by medieval Ashkenaz, Jewish communities who lived in Germany and Northern France. The manuscripts do not have any strong artistic connections to the synagogue engravings of late antiquities and were likely inspired by Christian Gothic traditions. Both the figures here were produced in Germany.

Figure 1 is part of a larger image from the Regensburg Pentateuch. The manuscript has six illuminations, and this specific figure is a part of a larger, full-page illustration which depicts the major events in the life of Isaac. In it, the moment when Abraham is stopped from killing his son by the angel is captured. The angel is emerging from the heavens, the ram is seen stuck in a bush behind Abraham, while Abraham wears a red robe and a conical hat. Isaac is seen kneeling on the altar, his posture mimicking that of the ram, and the shape of the mountain can be seen in the background. The angel is given an eagle’s head but has a human hand stopping the sword; This is likely to avoid depicting a divine creature with a human head. However, this particular artistic point of view was not necessarily shared among all Jewish communities at the time, as we can see the angel in Figure 2 has a human head. There are two addition details specific to this image. First is the hat Abraham wears. This conical white hat was typical of German Jewish clothing at the time, and it is reflected here, emphasizing and placing the contemporary community in the scene. The second detail is the woman being held by the figure on the left. This is Sarah being shown the act by Satan, who tried to convince her to prevent Abraham from following God’s command. This moment does not occur in Genesis, but is rather based on a midrashim – a rabbinical commentary and expansion upon the original texts. The commentaries and midrashim were taught along with the main Torah text, and while not a part of the Binding in Genesis, were important enough in the context of Isaac’s life that it was included.

Figure 2, manufactured in Southern Germany, displays more of the passage. It is taken from a mahzorim prayer-book. At the bottom of the page the donkey and the two servants are seen, while Abraham, again clad in a red robe, and Isaac climb the mountain on the left. To the right the angel again stops Abraham, with the ram stuck (perhaps more convincingly) in the bushes and Isaac is laid upon the altar. The angel this time has a human face, but the layout is extremely similar to Figure 1. The orientation of the scene is the same, with the angel appearing to Abraham’s back, behind which the ram is stuck. However, the ram and Isaac both face Abraham, which wasn’t the case in Figure 1. This particular image was not created by a Jewish artist, but was illustrated by a Christian, likely with direction from the Jewish commissioners. Despite the direction, there are several objects which indicate this, such as the red and blue colored clothes which were typical of Christian figures in Gothic art. Secondaly, the candle near the altar is one typically seen in churches during Easter service but is not one used during any Jewish holidays. Finally, the direction the scene is read is from left to right, rather than right to left – the direction Hebrew is read. It is interesting that the symmetry between Isaac and the ram is lost here. The illustration itself is very richly decorated. In both scenes, the angel is grabbing the blade at the moment of the downswing and pointing to the ram, visually demonstrating the lines of conversation between it and Abraham. It is interesting that neither altar agrees with the Vulgate’s bundle of wood or the Jewish altar of stones, instead being altar blocks in both.

Sources

The Codex Gigas (2002, June, 3). National Library of Sweden. https://www.kb.se/in-english/the-codex-gigas.html

Gutmann, J. (1987). The Sacrifice of Isaac in Medieval Jewish Art. Artibus et Historiae, 8(16), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/1483301

Isidore, O. S. & Josephus, F. (1200) Devil’s Bible. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, to 1230] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667604/.

Sabar, S. (2009). “The Fathers Slaughter their Sons”: Depictions of the Binding of Isaac in the Art of Medieval Ashkenaz. Images. 3. 9-28. 10.1163/187180010X500162.