The Reina-Valera Bible

The Reina-Valera Bible

By Lucía S. Bezzecchi Petroff

Introduction

The Reina-Valera Bible owes its current name to Spanish protestant theologians by the name of Casiodoro de Reina (1520-1594), who first translated the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Spanish, and Cipriano de Valera (1531-1608), the man who carried out the first revision of the translated text after its publication. The efforts of these two men, at a time when it was dangerous to express religious dissidence, resulted in the first protestant Bible ever to be printed in Spanish, which continues in use even today. This article explores the origins and characteristics of one of the foremost Protestant bibles of its time.

| Categories | Bible |

| Title | Biblia Reina-Valera |

|---|---|

| Date | 1602 |

| Place | Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Contributor(s) | Reina, Casiodoro de (translator) Valera, Cipriano de (editor) Lorenzo, Jacobo (printer) |

| Language(s) | Spanish, translated from Hebrew and Greek |

| Source | BNE Catalogue |

History of the Bible

The first version of this Bible was simply known as the Biblia del Oso (the “Bear Bible”) because of the illustration of a bear in its titular page. Casiodoro de Reina based his translation on several pre-existing biblical texts: for the Old Testament, he used the Hebrew Bible printed by Daniel Bomberg (1525) and for the New Testament, he took Erasmus’ Textus Receptus from 1516. This Bible, as well as its Valera’s edition, surfaced in a period of religious upheaval, in which the Roman Catholic Church was fighting against Protestantism and trying to ban heretic texts. Despite the danger it entailed, Casiodoro de Reina realized the need for a Bible in a vernacular language and began the to translate the aforemention texts.

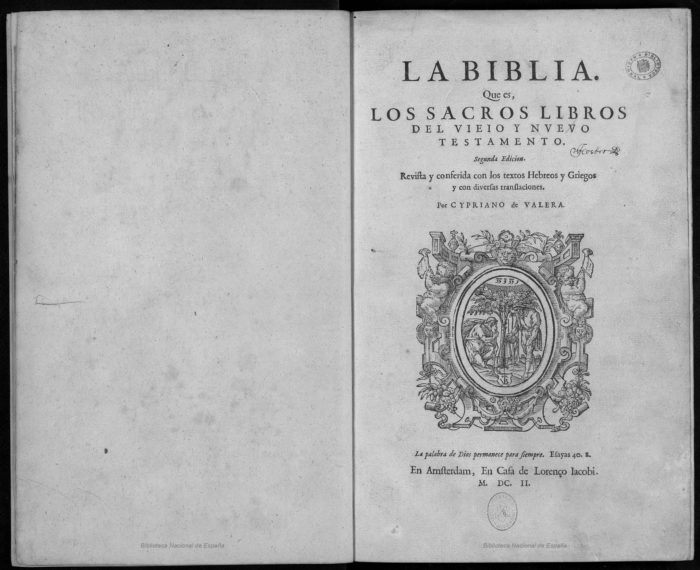

At the time, both him and Cipriano de Valera were monks of the Spanish Order of Saint Jerome located in the outskirts of Seville, Spain, a city that had been vastly influenced by Protestantism. When both monks became adherents to the Protestant movement, they were forced to flee the country around the year 1559. While in exile, Reina printed his Bear Bible (on which Valera had also collaborated as his pupil), a text served as the first Protestant Bible for the Spanish-speaking followers, in Basel, Switzerland, in 1569. Valera, on the other hand, eventually settled in England and would remain there until his death. He began to revise the Bear Bible in 1582, a task that took him approximately twenty years to complete. The final revised text was published in Amsterdam in 1602, by printer Lorenzo Jacobi, whose mark can be seen at the bottom of the emblem. This time the Bible adopted the name of the Biblia del Cántaro (or the “Pitcher Bible,”) due to illustration on its titular page.

“La Biblia, que es los Sacros Libros del Viejo y Nuevo Testamento. Segunda edicion revista y conferida con los textos hebreos y griegos y con diversas translaciones por Cypriano de Valera.” (Amsterdam, 1602)

The Meaning behind the Emblem

The emblem is composed of a drawing of two men standing in front of a tree, one of them kneeling and working the earth and the other one on his feet while watering the spot with a pitcher (or cántaro). Later interpretations of this illustration have widely agreed that this image is alluding to a passage of the Bible itself, in which Saint Paul addresses the Corinthians:

I planted the seed, Apollos watered it, but God has been making it grow.

So neither the one who plants nor the one who waters is anything, but only God, who makes things grow. He who plants and he who waters are one, and each will receive his wages according to his labor. (1 Corinthians 3:6-8)

In this case, the gardeners can be a representation of both Reina and Valera. While Reina, the translator, plants the seed (the word of God) in the soil, Valera waters it, nurturing it. But it is God, depicted here through the sunrays (and its name in Hebrew), who makes it grow into a tree. In the drawing, Reina and Valera are but the keepers, protectors and servants of the word of God. And a tree, the result of their efforts, is seen between them in two stages: as it sprouts and as it reaches maturity. The tree symbolized the faith in the word of God, nurtured by the gardeners and cultivated by God. Furtheremore, the emblem is accompanied by the phrase “The word of our God endures forever” (Isa. 40), which refers to the immortal aspect of God and its teachings, in contrast to the mortality of its humble servers, who are nothing but facilitators, vehicules, through which the sacred texts can reach others.

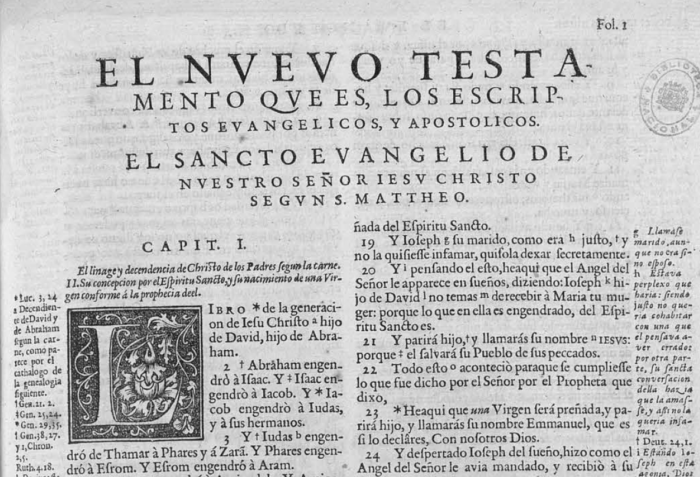

Inside the text: the Gospels

The Reina-Valera Bible follows the same chapter order as its predecessor, and includes the four Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Valera himself stated that his intention behind the revision was not to change the original text —recognizing and praising the efforts of his master— but to enrich it through notes and ocasionally updating some words for better comprehension. While the Bible is devoid of illustrations, all chapters have an initial capital letter ornated in a similar style, except for the one at the beginning of the Gospels section. This capital letter is the only one in the text set against a dark background and decorated with the drawing of a flower.

Going further into the Gospel according to St. Matthew, it is easy to see some stylistic changes to the new version, such as capitilizing Jesus’ name in the new version (Iefvs vs. IESVS) and the extensive amount of notes in cursive, which the way to recognize Valera’s additions (cross-references and further explanations of the text-) Another incorporation to this edition was a brief sentence at the upper corner of each page, which helps the reader to navigate the contents of the Bible by summarizing the contents of each page. The interactive image below shows illustrates the thoroughness of Valera’s notes in contrast with the same chapter in Reina’s translation.

Bibliography

- Roldán-Figueroa, Rady. “‘JUSTIFIED WITHOUT THE WORKS OF THE LAW’: CASIODORO DE REINA ON ROMANS 3,28.” Nederlands Archief Voor Kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History 85 (2005): 205–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24013131.

- López, Sergio Fernández. “LAS LLAMADAS BIBLIAS DEL EXILIO EN ESPAÑA: SOBRE SU DIFUSIÓN EN LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA SEGÚN EL TESTIMONIO DE PEDRO DE PALENCIA Y OTROS INTERROGATORIOS INQUISITORIALES.” Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 73, no. 2 (2011): 293–301. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41479779.

- Verd Conradi, Gabriel María. 1971. «Casiodoro De Reina, Traductor De La Biblia». Estudios Eclesiásticos. Revista De investigación E información teológica Y canónica 46 (179):511-29. https://revistas.comillas.edu/index.php/estudioseclesiasticos/article/view/18642.

- Alonso Rey, María Dolores. “Los emblemas de las Biblias del Oso y del Cántaro. Hipótesis interpretativa”, Imago. Revista de Emblemática y Cultura Visual, 4 (2012): 55-61. doi: 10.7203/imago.4.1443.

- Monreal Pérez, Juan Luis. 2021. «Biblismo, Lengua vernácula Y traducción En Casiodoro De Reina Y Cipriano De Valera». Futhark. Revista De Investigación Y Cultura, n.º 9 (mayo). https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/futhark/article/view/16171.