La Biblia del Oso (The Bear Bible)

By David Macchi Franco

La Biblia del Oso

The first translation in Spanish of the complete bible directly from the texts in Hebrew and Greek is known as the Bear Bible (la Bible de l’Ours) because of the printer’s emblem that depicts a bear eating honey from a honeycomb in a tree. This publication was censored by the Catholic Church, for it was seen as an attempt to undermine the authority of the stablished versions, in consequence the translator, Casiodoro de Reina, was persecuted. The following research presents information about this translator, the bible he worked on and its reception and impact at the time and today. Additionally, the gospel of John passage in which the Incredulity of saint Thomas is shown, will be analyzed considering the pictural representations of it at the time of the diffusion of this bible.

| Title | La Biblia del Oso (The Bear Bible – La Bible de l’Ours) |

|---|---|

| Date | 1569 – 16th century |

| Place | Printed in Basel, Switzerland |

| Contributor(s) | Casiodoro de Reina (1520-1594) – Translator Thomas Guarin (fl. 1547-1592) – Editor Samuel Apiarius (fl. 1554-1590) – Printer |

| Language(s) | Spanish – Old Testament translated from the Hebrew. New Testament from the Greek |

| Source | Ayuntamiento de Madrid, Facsimil Edition, University of Coimbra, Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia (Pegasus Bible) |

| Format | [30] p., 1438 col., [1] p. ; 544; 508 col., [2] p. ; 4º (25 cm) |

The life of Casiodoro de Reina

There is no unanimity among scholars concerning Casiodoro de Reina’s birthplace but according to Manuel Diaz’s research, Casiodoro was born in 1520 in Montemolín, Kingdom of Seville, entered the Hieronymite monastery of San Isidoro del Campo, and studied in the University of the same city before leaving in 1557 towards Geneva, due to the discovery of a Protestant community in Seville. Some time after, unhappy in Geneva, he moved to Frankfurt, and later sought refuge in England, where Queen Elizabeth I allowed him to preach to persecuted Spaniards. In 1562, he became a pastor of the Church of England. Constantly persecuted by the Inquisition, Spanish authorities, and ultra-orthodox Calvinists, he traveled through Frankfurt, Heidelberg, France, Basel, and Strasbourg, eventually settling in Antwerp in 1568. When the city was seized by Spanish forces in 1585, he returned to Frankfurt, where he tried to obtain citizenship in 1573; while he waited to be appointed preacher, he supported himself through a silk trade. At over 70 years old, he was elected assistant pastor in 1593 and served for eight months until his death on March 15, 1594.

In the StoryMap that follows, biographical data obtained by the researcher Constantino Bada Prendes was used to give another perspective of the translator’s life. Bada Prendes proposes another view on the information that refers to the birthplace and some additional facts.

The translation of the Bible into Spanish

The textual source used by Cassiodorus for the translation of the New Testament is Erasmus of Rotherdam’s Novum Instrumentum Omne, an edition prepared by the humanist in Greek and Latin from various manuscripts including 10th century sources. It is thought that Cassiodorus may have used Robert d’Estienne’s version published in 1550.

The source used for the Old Testament was the Hebrew Bible, printed in Venice between 1524 and 1525 by Daniel Bonberg, by Jacob ben Chayim ibn Adonijah, a Jew of Spanish origin who converted to Christianity. Cassiodorus also made use of the Sanctus Paganini and Ferrara bibles of 1553.

Casiodoro’s work of translation began during his stay in England and was prolonged during hard years marked by inquisitorial persecution and economic difficulties. Printing began at the end of 1568, financed by funds bequeathed by Pineda for this purpose before his death. The printer Oporino originally received the commission, but his death delayed the process. Guarín took the commission and entrusted it to Samuel Apiarius, who undertook the task of producing 2600 copies.

Despite Cassiodorus’ efforts to have his translation accepted by the Church, his work was censored, ordered confiscated and Philip II put a price on his head. Of the 2,600 copies, 32 copies survive today, many of which bear the printer’s mark of the Pegasus, imposed over the original bear in an effort to save them from destruction because of their ease of identification.

The following map shows the libraries and institutes that own one or more copies, as well as the link to the catalogue for consultation.

The Bear Emblem

The emblem that appears in the Bible’s frontispiece and that gave it the name by which it is commonly known has been interpreted by many authors like A.G. Kinder, José Carlos Nieto and María Dolores Nieto. The following interpretation contains elements from the three authors plus the analysis made by Vincent Parello, in this way editorial, historical, and cultural perspectives are appointed.

Taking into consideration the dynamic between the graphical elements hypothesized by the authors, one possible interpretation of the emblem goes as follows: the tree, that endures through time, contains the honey that seeps out by the striking of the mallet, then the bear takes the sweet delicacy even though the bees attack him to keep the honey for themselves; meaning that the Roman Church, that enclosed the Word of God over the centuries, is hit by the Lutheran reform allowing the testaments to be accessible to the new Church that suffers the attack of the representatives of Catholicism.

Because of its bad reception by the Catholic Church, the majority of the Casiodoro’s bibles, easily identifiable by the emblem were systematically destroyed, Casiodoro himself was pursued and many times accused of heterodoxy among other crimes, showing that like the bees Catholics attacked fiercely and like the bear the Lutherans persisted in their quest for the wisdom they deemed worth fighting for.

El dedo en la llaga – Le doigt dans la plaie

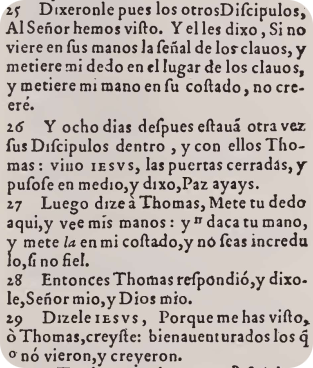

25 So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord!” But he said to them, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

26 A week later his disciples were in the house again, and Thomas was with them. Though the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!”

27 Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.”

28 Thomas said to him, “My Lord and my God!”

29 Then Jesus told him, “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

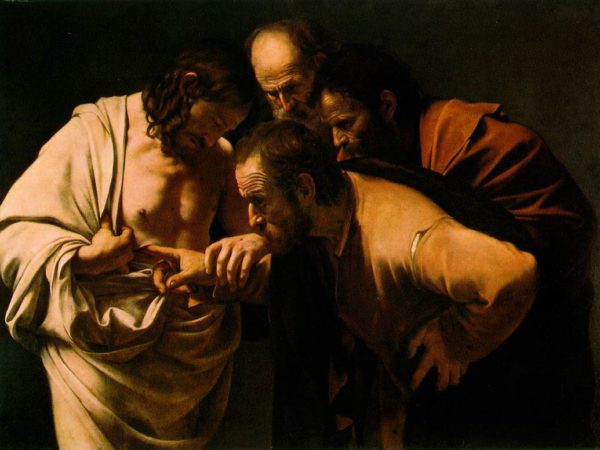

The finger in the wound is an episode that takes place after the death of Christ, in which the apostle Thomas, incredulous about the resurrection, states that he will only believe when he sees Christ and can put his finger in the wounds. Shortly afterwards the risen Christ appears before him and asks him to touch his wounds, which the apostle does. Thomas immediately replies: “my Lord, my God”, to which Christ replies: “because you have seen me, oh Thomas, you believed: blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed”. This passage is found only in the Gospel of John, chapter XX, between verses 25 and 30.

It is indeed one profoundly significant episode, since according to the Church it presents the virtue of faith when Jesus says: “Blessed are those who believe without seeing” and on the other hand it censures the scientific spirit of St. Thomas who demands proof in order to be convinced. This scene condenses the religious philosophy that imposes itself on the ethos of demonstration, characteristic of the scientific method that considers true that which can be verified.

Several artists have depicted this scene throughout history in paintings and sculptures. It can be seen in the works selected below that there is stability in the way in which the figures of Christ and St Thomas are presented; minor variations, such as the side on which Christ’s wound and the witnesses to the encounter are found, are noted.

Conclusions

The Bible, as both a spiritual and political document, wielded great power for several centuries. The sixteenth century witnessed the Catholic Church’s struggle to maintain the legitimacy of its political hegemony emanating from the Holy Scriptures, as well as the Reformers’ effort to escape censorship in order to contest the corrupt exercise of Catholic authority. The translations of the Old and New Testament, the opposition to the Council of Trent and the self-definition of the emerging nations materialised their tensions in the publishing practice of the time, which was marked by persecution and censorship.

Added to this, the use of cryptic emblems by printers and the multiple graphic representations that Bible passages inspired, show that image and text move together in a dynamic in which it is sometimes difficult to trace which is the origin of the idea, the word or the drawing. However, it is clear that both, word and line, are tools that convey through time and across borders, the essence of human thought both in its spiritual and rational dimension.

Finally, it is evident that the Bible is also a useful source of information in the academic world to discuss historical, ethical and artistic concepts, around which it is possible to apply different methodologies of analysis and dissemination, such as digital tools and the internet.

Bibliography

- Alonso Rey, María Dolores. «Los emblemas de las Biblias del Oso y del Cántaro. Hipótesis interpretativa.» IMAGO Revista de Emblemática y Cultura Visual, 2012: 55-61.

- Bada Prendes, Constantino. “La Biblia del Oso de Casiodoro de Reina primera traducción completa de la Biblia en castellano.” Salamanca: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 2017. 610.

- Díaz, Manuel. “450 Aniversario De La Biblia Del Oso – Casiodoro De Reina”, Exposición Gráfica. Islas Canarias: Facultad Teológica Cristiana Reformada, 2019.

- Parello, Vincent. «L’ours, les abeilles et le miel : le frontispice de la Biblia del Oso.» eHumanista, 2022: 90-101.