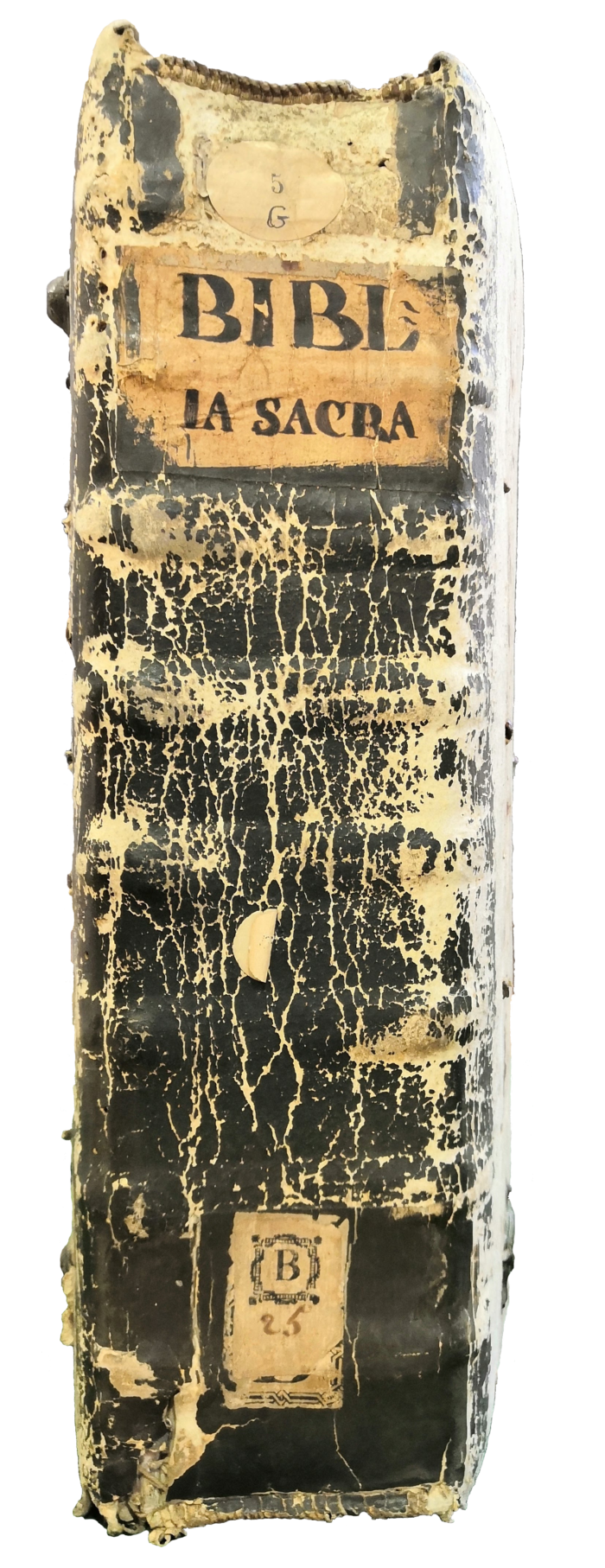

Biblia sacra, ex translatione S. Hieronymi, cum epistola ad Paulinum, prologis et capitulis

Biblia sacra, ex translatione S. Hieronymi, cum epistola ad Paulinum, prologis et capitulis

by Rosenn Nicolas and Louise Chanson

Introduction

| Title | Biblia sacra, ex translatione S. Hieronymi, cum epistola ad Paulinum, prologis et capitulis |

| Date | second half of the 13th century |

| Format | 36,9 x 26 cm |

| Pages | 541 |

| Language | Latin |

| Place | Municipal Library of Besançon (France) |

| Sources | photographic credits to R. Nicolas |

Particularities of the content

Context

It must be said that in the 13th century and in the Middle-Ages in general, the book production was mainly directed by monks in their abbeys. Therefore, the Crusades, the development of universities, and the rise of the mendicant order, had a crucial influence on the Bible production at that time.

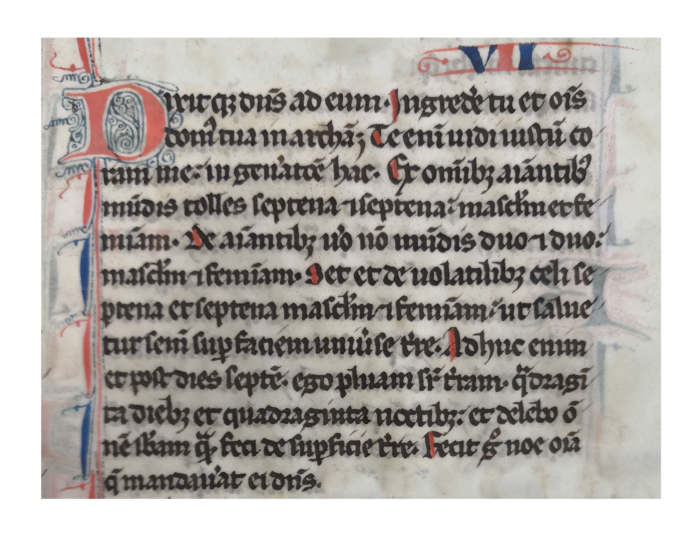

In the case of our Biblia sacra, from the top of its 36,9×26 centimeters, it is slightly larger than the actual average (34×24 cm) of the time. In the same way of many 13th century Bibles, it only has one volume in order to transport it, and it also introduces a vellum parchment (thinner and whiter) which gave more legibility and elegance to the copy.

This is a Vulgate, a Bible translated by Saint Jerome into Latin from Greek and Hebrew. It was considered as the best translation of the Bible. Even revised, it was the reference Bible of the Catholic Church until 1979.

It is complete with the Hebrew names. That is to say that it presents the whole of the Old and New Testaments following a standard order enriched by prologue and epilogue (here the letter to Paulin). One notices the titles in the upper margin of each page, the chapters are numbered according to a new system (which is essentially that of modern Bibles). Everything is therefore designed for ease of use. That complete form did not exist before the 9th century and was the norm only from the 13th century.

This Biblia sacra is finally a good example of the 13th century Bibles. Indeed, that period was a turning point in their production in terms of structure because it had combined since the 9th century little changes which gave birth to a new form. Actually, it even became the standard which have persisted until nowadays.

The content

As some of the 13th century manuscripts, this one is richly illuminated with about 60 illuminations and vignettes. That is not counting the initials. The most important of all is certainly the first. It probably shows Jerome of Stridon, famous as Saint Jerome.

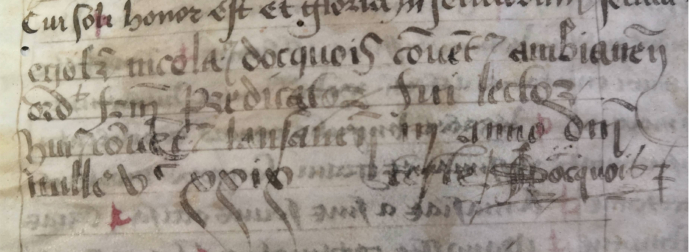

This special copy has two main particularities. First, its endleaves. They are actually parchment scrolls written in Hebrew. It may be a part of the Torah. On the upper endleave, we can also read little margin notes. On the under endleave, there is an ex-libris “Estavaye-1580”. It is the only clear precision we have to retrace the origin of this copy. Second, there are four sheets of parchment where we can read a writing from the 16th century. We supposed they had been added to the current binding. Thus, we can conclude the binding comes from the 16th century.

The four first sheets from the 16th century introduce a sort of index of biblical names like Adam, Eve or Noah. It gives their location by chapter. At the end, we can also read:

in anno domini/mille V XXIX (1529)

Transcription, Translation

Here is a parallel between an extract form our Biblia Sacra and first a transcription and then a translation in French. We chose to introduce the whole transcription and translation by putting two images in one in order to easily navigate from the transcription to the translation.

The Construction of Noah’s ark and its representations

There is a plethora of representations of the Great Flood. Most of the time, those representations illustrate one of the four following moments: the construction of the ark, the ascent, the flood in itself, and the aftermath (with the dove especially). This study focuses on three representations, throughout history, of the construction of Noah’s ark.

Middle Ages and illuminations

The first representation is an illumination from the 14th century (recent research dates it back to circa 1330) that belongs to one of the Bibles kept at the Clairvaux Abbey (France), a Cistercian monastery, founded in 1115 by Saint Bernard. The manuscript can now be found at the municipal library of Troyes

On the red background of this illumination, a rather young-looking man, dressed in a blue tunic, is holding an axe while staring at the hull of what will become an ark. Illuminations are highly codified, for instance depicting Noah sideways means that the character is caught in the action of cutting trees (like the ones on the background probably) to build the ark. Placement and size are two different ways of indicating what element is important. Thus, the biggest an element is, the more important it is ; everything placed on the right side is automatically more important than what is located on the left side. What is important then on this illumination is not Noah or the ark, but the both of them, meaning the construction of the ark by Noah in itself.

(CNRS)

Illuminations started to appear during the 7th century. They had only an ornamental function as they were considered as a means to showcase the text. Texts could exist without images but images couldn’t exist without supporting a text.

Renaissance and paintings

The second representation is one of Raphael’s latest paintings. The Italian painter (1483-1520) painted at the Vatican palace between 1517 and 1519, fifty-two episodes of the Bible, which by their richness earned him the nickname of “Raphael’s Bible” (De Vecchi, Raffaello, 1975). Raphael did four paintings representing Noah’s cycle.

(Roma Interactive)

The Construction of the Ark represents a much older version of Noah (the white of his beard aging him by a good three decades from the younger version of the illumination), with his three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth. On the painting, only the three sons are working on cutting wood for the ark. Noah does not participate to the physical effort but he seems to be giving instructions to one of his sons. Unlike the illumination, the action of cutting the woods is much more clearer on Raphael’s painting. Indeed, the absence of clothes makes the tensed muscles very apparent and thus the sons’ effort more visible. The presence of wood chips at their feet, representing the aftermath of said action, makes the later more tangible while it was more of a deduction from seeing the axe with the illumination. It is interesting to see that two of the sons have axes in their hands while the last one is using a bucksaw, which is a more contemporary tool. There is thus an adaptation of the biblical episode to the artist’s realities of his time. On the background, the ark is only at its beginning, as the wooden structure of the hull is the only thing visible.

With Raphael’s painting, the link between the text and the image is however severed. The text is indeed nowhere to be found. The image is no longer in a relation of subordination to it but can exist outside of it perfectly well. The image still keeps a decorative function, but it can be independent and as important as the text now.

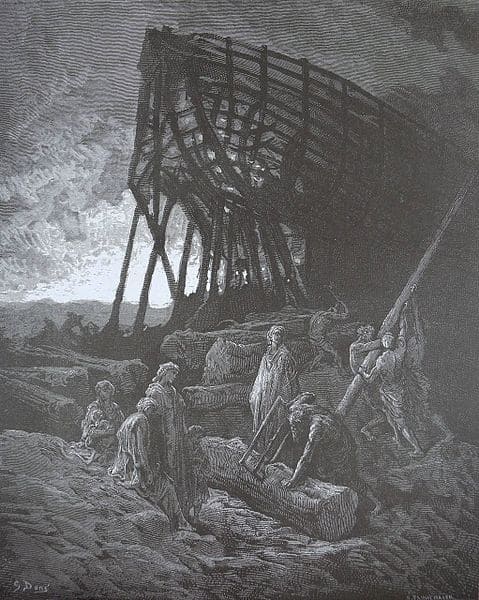

19th century and engravings

The third representation is a wood engraving made by the French illustrator and engraver Gustave Doré (1832-1883). Throughout his career, Doré had taken a liking to brighten up books that he did not write with some of his engravings. It is the case of Paradise Lost, an epic poem written by John Milton (1608-1674), reedited with Doré’s engravings in 1866. The engraving representing the construction of the ark comes from the eleventh book (out of twelve).

(Internet Archive)

On the foreground of the engraving, some men are working. One of them, old and bare foot, is cutting a tree trunk with the same bucksaw depicted by Raphael centuries before. Another man is holding with both hands an axe above his head. On the right side, three men (Noah’s son maybe) are trying to carry or to raise a beam of wood. In front of the old man, a woman is cradling a baby and three other characters, who could be part of Noah’s family, are looking at the workers. The ground is littered with tree trunks. On the background, the structure of the hull stands out on the sunset light, which indicates that the effort to build the ark is a long-term process. The gigantic dimensions of the ark, bigger that the illuminated one, is given by the fact that the ark can’t fit within the engraving frame.

Once again, the engraving function is to illustrate Milton’s poem. However, contrary to the illumination, Doré’s engraving is as important as Milton’s text. The image comes back to the text in a new relationship with the text: one of complementarity.

The representation of the construction of the ark evolves with the realities of the different periods and that can be seen through the different tools used by the characters and the different technics used by the artists. The perspective, for example, allows the representation of several spaces, which allow the artist to play with the size of every element in the composition and stress their importance. The focus on the three representations chosen is mostly on Noah (and his family). Except for Doré’s, on which the first element that is seen is the ark overhanging the rest of the engraving and making the characters look very small, even insignificant. The relationship between the text and the image shifts in a much more visible way. From the subordination of the image to the text, the image grows in independence and in importance, until being totally separated from the text and thus existing alone. However, the 19th century sees the return of the image to the text, in a complementary relationship this time around.

Sources

La Bible de Jérusalem. Nouvelle éd., Revue et Corrigée, Editions de Cerf, 2005.

De Hamel, Christopher. The book: a history of the Bible. Phaidon, 2001.

De Vecchi Pierluigi, Raffaello, Milan, Rizzoli, 1975.

Garnier François, Le langage de l’image au Moyen Âge : Signification et symbolique, Paris, Le Léopard d’or, 1996.

Henry Tom, Joannides Paul (dir), Raphaël. Les dernières années, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2012.

Paolucci Antonio , Raffaello in Vaticano, Firenze, Giunti, 2013.

Renonciat Annie, Gustave Doré, Paris, A.C.R., 1983.

Stirnemann, Patricia. «La naissance de la Bible du 13e siècle », Lusitania Sacra. n°95-104, Juillet-Décembre 2016, p. 95-104.

Victor Benjamin, « Une Bible portative du XIIIe siècle dans les collections de l’UQAM ». Memini. Travaux et documents, no 15, décembre 2011, p. 23‑38. journals.openedition.org, https://doi.org/10.4000/memini.393.

« Juxtapose », Juxtapose, https://juxtapose.knightlab.com.