Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples’ bible

Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples’ bible

By Laurie Hennequin

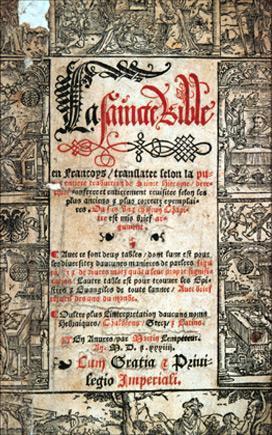

| Title | La Saincte Bible. en francoys translatee selon la pure et entiere traduction de sainct Hierome | conferee et entierement revisitee | selon les plus anciens et plus correctz exemplaires ou sus ung chascun chapitre est mis brief argument | avec plusieurs figures et histoires : aussy les concordances en marge au dessus des estoilles, diligemment revisitees. Avec ce sont deux tables… |

| Contributor | Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (1450-1537) |

| Date | 1530 |

| Editor | Martin Lempereur, Anvers, Belgium |

| Language | French |

| Source | https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1512356p/f33.item |

Presentation of the author

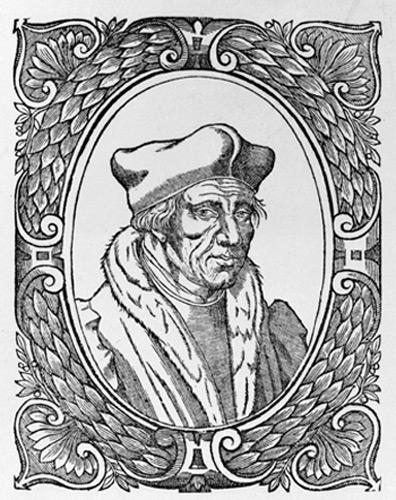

This Bible is known as the first translation of the Bible from Latin into French, by Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples. We will begin by looking at this translator of the Bible, who played an important role in Catholicism in the early 16th century.

Jacques Lefèvre, born in 1450, was a French Catholic theologian and humanist. During the first part of his life, he was a professor of arts and philosophy in Paris until 1507.

He was the defender of a number of reformist ideas and the source of many polemical writings. In 1520, he was appointed vicar and later bishop of Meaux, creating the Cénacle de Meaux by gathering other theologians around him, with the aim of improving the training of priests through preaching and popularising the Scriptures.

Jacques Lefèvre was one of those who defended the renewal of ecclesiastical studies and encouraged their criticism. He had already been singled out for these ideas, and it was his translation of the Vulgate version of the Bible, initially of the New Testament, that prompted new proceedings against him in 1523. This translation included around sixty corrections based on the Greek version of the Bible, as well as a recommendation to read the Holy Scriptures in the vulgar language. Jacques Lefèvre’s New Testament was burnt by court order.

In 1525, Jacques Lefèvre was dismissed from his post and the cenacle in Meaux was dissolved; he went into exile in Strasbourg. His complete version of the Bible was not printed until 1530, when he was appointed tutor to Prince Charles under François the First. He spent the last years of his life in Nérac in south-west France.

Context

This Bible was originally translated by Jacques Lefèvre to facilitate the work of preachers who preached the good word in French to the people. The translation is based on the Vulgate version, in Latin, translated by Saint-Jérôme in the 4th century, but with modifications based on the Greek text. This first translation of the Old Testament was published in Paris in 1523 and 1525, and its success was considerable, thanks to advances in printing. However, in 1526, this translation led to the Parliament banning all translations of the Scriptures into French. But thanks to the support of King François the First and Marguerite of Navarre, Jacques Lefèvre was able to pursue his translation, this time with the support of the doctors of the University of Louvain. Regularly revised, this translation served as a reference in France for almost a century.

At the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries, this translation took place in the context of a nascent humanism, which itself gave rise to the Reformation movement. At the same time as Jacques Lefèvre’s translation, Olivétan also translated from the original Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible.

Transcription and comparison with Olivétan’s bible

Given the proximity in time of the two translations of the Bible by Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples and the Bible by Olivétan (1530 and 1535 respectively), it would be relevant to compare the translation of the two chapters (here chapter 17 of the Revelation), given that one is based on the Latin version and the other on the original Greek and Hebrew versions.

As we can see, there are many differences between the two versions, but they have almost no influence on the substance of the text. Most of the differences are to be found in the spelling of certain recurring words: et et &, veu et veues, roix et roys, etc. Some differences in syntax are also notable: in the Olivétan Bible we find greater use of capitals (‘Dieu’, ‘Roys’, etc.), and some words are spelt in a more modern way despite only five years’ difference between the two versions. A character that we find in Olivétan’s version but that is not present in Etaples’ version is the question mark. We can also see that Etaples’ translation contains more abbreviations than Olivétan’s version and that the verse structure may vary between the two versions. Olivétan’s version also seems more descriptive in that certain details are added, such as the description of the woman’s dress. Some of the words found in Etaples’ version are modified when we analyse Olivétan’s version: the word “prostitution” is replaced on several occasions by “paillardize”.

Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples’ version

Olivétan’s version

Et vint lung des sept anges qui Auoient les sept phioles : & par La a moy disant : viens je te mon Streray la damnatio[n] de la gran De paillarde / laquelle se sied sus Plusieurs eaues : avec laquelle les roix de la Terre ont fait fornication / & ceulx qui habite[n]t En terre se sont enyurez du vin de la prostitu Tion. Il me tra[n]sporta en esperit au desert. Et Je veis vne femine assise sus vne beste reuge Plaine de noms de blaspheme / ayant sept te- Stes & dix cornes. Et la femme estoit aviron- Nee de pourpre / & de marguerites : aya[n]t vng Calice dor en sa main plain de abomination & De immundicite de sa fornication. Et en son Front le nom escript / mystere : la grande Ba- Bylone mere des fornicatio[n]s & des abomina- Tions de la terre. Je veis vne femme enyuree Du sang des sainctz / & du sang des martirs De Jesus. Et quant ie la veis / ie me suis es- Merueille par grande admiration. Et lange Me dist : Pourquoy te esmerueille tu : Je te di- Ray le mystere de la femme : & de la beste quy La porte / laq[ue]lle a sept teste & dix cornes. La Beste que tu as veu / a este / & nest plus : & doibt Mo[n]ter de labisme / puis sen ira a perditio[n]. Et Se esmerueilleront les habita[n]s de la terre / des Quelz les noms ne sont point escrips au liure De vie des la constitutio[n] du monde / voya[n]t la Beste laq[ue]lle estoit / & nest plus. Et cestuy est le Sens a celny q[ui] a sapience. Les sept testes sont Sept montaignes / sus lesquelles la femme se Sied : & sont sept roix : les ci[n]q sont mortz / lung est / & lautre nest point encoire venu. Et qua[n] Il sera venu / il fault quil demeure brief te[n]ps. Et la beste qui estoit & nest plus / icelle est la Huytiesme / & est des sept / & yra a perdition. Et les dix cornes lesquelles tu as veu / sont Dix roix qui nont point prins encoire regne : Mais prendront puissance en vng temps com Me roix / avec la beste. Iceulx ont vng co[n]seil : & bailleront leur vertu & puissance a la beste Iceulx bataillero[n]t avec laigneau / & laigneau Les vaincra : *car il est le Seigneur des Sei- Gneurs & le Roy des roix. Et ceulx qui sont Avec luy / sont appellez / & esleuz & fideles. Et Me dist : les eaues lesquelles tu as veu ou la Paillarde se sied / sont peuples & gens / & lan- Gues. Et les dix cornes q[ue] tu as veu a la be- Ste / Iceulx hayront la paillarde / & la fero[n]t de Solee & nue / & mengero[n]t ses chairs / & la brus- Lero[n]t en feu : car dieu a mis ce en leurs cueurs Quils faice[n]t ce quil luy plaist / & quils donne[n]t Le royaume a la beste / iusq[ue]s a ce q[ue] les parol Les soient aco[m]plies. Et la femme laquelle tu As veue / est la gra[n]de cite laquelle a son regne Sus les roix de la terre.

Et vint lung des sept anges qui auoient les sept phioles / et parla avec moy / me disant : vien ie te monstreray la damnation de la grande paillarde / laquelle se sied sur plu sieurs eaues : avec laquelle les Roys de la Terre ont Paillarde / et ceulx qui habitent en terre se sont enyurez du vin de la paillardize. Et me transporta en esperit au desert. Et ie veis vne femine assise sus vne beste de couleur Descarlate / pleine de noms de blaspheme : ayant sept testes et dix cornes. Et la femme estoit enuironnee de pourpre et de escarlate : et doree dor et de pierre precieu- Se/ et de perles : ayant vng hanap dor en sa main plein de abomination et ordure de sa paillardize. Et en son Front le nom escript / *mystere : la grande BaBylone* mere des paillardizes / et des abominations de la ter- re. Et veis la femme enyuree du sang des sainctz / et du sang des martyrs de Jesus. Et quand ie la veis / ie mesmerueillay par grande admiration. Et lan- Ge me dist : Pourquoy te esmerueille tu ? ie te diray le mystere de la femme : & de la beste qui la porte / laquelle a sept teste et dix cornes. La beste que tu as veue / a este / & nest plus : & doibt monter de labysme / et sen ira a perdition. Et se esmerueillero[n]t les habitans de la terre / desquelz les noms ne sont point escritz au liure de vie des la fondation du mo[n]de / voyant la beste laq[ue]lle estoit / et nest point / co[m]bien q[ue]lle soit. Et icy est le sens lequel a sapience. Les sept testes sont sept montaignes / sur lesquelles la femme se sied : et sont sept Roys. Les cinq sont cheuz / lung est / et lautre nest point enco- re venu. Et quand il sera venu / il fault quil demeure brief temps. Et la beste qui estoit et nest point / cest aussi le Huytiesme Roy / et est des sept / et va a perdition. Et les dix cornes lesquelles tu as veues / sont dix Roys qui nont point prins encore regne : mais pren- dront puissance en vng temps comme Roys / avec la beste. Iceulx ont vng conseil : et bailleront leur puis- sance et autorite a la beste. Iceulx batailleront con- tre laigneau / et laigneau les vaincra : car il est le Sei- gneur des Seigneurs / et le roy des roys. & ceulx qui Sont avec luy appellez / et esleuz & fideles. Et Me dit : les eaues lesq[ue]lles tu as veues ou la pail- larde se sied / sont peuples / & tourbes / & gens / et langues. Et les dix cornes que tu as veues a la beste / iceulx hayront la paillarde / et la feront desolee & nue / & man- geront ses chairs / & la brusleront en feu : car Dieu a mis en leurs coeurs quils facent ce quil luy plaict / & quilz sa Cent une volunte / & quilz do[n]nent le royaume a la beste / iusque a ce que les parolles de Dieu soye[n]t acco[m]plies. Et la fe[m]me laquelle tu as veue / est la grande cite laquel- le a son regne sus les Roys de la terre.

The Apocalypse : chapter 17

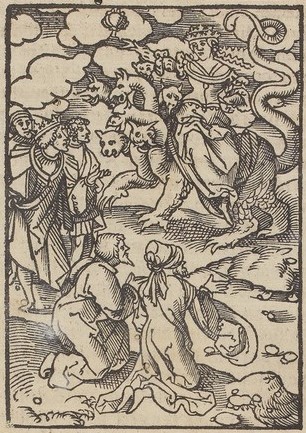

The Apocalypse, or Revelation, is the last book of the New Testament. The text, which is prophetic in nature, contains numerous allusions to the prophecies of the Old Testament. In this part of the Bible, the apocalypse is described as a great cataclysm before the return of Jesus Christ to Earth, illustrating the triumph of good over evil. Here, we will concentrate on chapter 17, of the 22 chapters of Revelation.

Here, chapter 17 breaks the chronology of Revelation. This chapter is a description of what made Babylon unworthy for divine clemency, in comparison with contemporary Rome. This chapter revolves around the symbolism of blasphemy and paganism. Babylon is depicted as an impure woman, sitting on a beast in the form of Roman power, in a desert, implying the absence of God. The prostitute illustrates the Roman Empire’s relations with other countries, based on its economic exploitation, benefiting a minority and neglecting the majority of the empire. It would then be the fate of the Roman Empire to fall as Babylon did.

The illustration

This chapter of the Revelation is illustrated by this image. We can recognise the woman riding the mystical seven-headed beast in a desert. The woman, adorned in regal finery, holds up a chalice filled with the blasphemies of the corrupt city of Babylon. The beast, representing renewed ancient Rome, is on the right of three kings who give it their power and authority. Beneath the beast are two people in a position of prayer, represented in opposition to the chosen ones who resist him.

Bibliography

Translations of the Bible in Latin and French during the 16th century

The Reform and the Bible : the sola scriptura

Humanism and translation of the Bible in vernacular languages