Lindisfarne Gospels

Lindisfarne Gospels: an illuminated treasure from north-east England

By Serhat Açar & Sonaj Kailas

Project synopsis

Here we will present to you the Lindisfarne Gospels, a remarkable bible manuscript that serves as an exemplary illustration of the transmission of knowledge and cross-cultural relations in early Christian life on the British Isles after its conversion from paganism.

| Categories | Details |

| Title | Lindisfarne Gospels |

|---|---|

| Date | c. 700 CE |

| Place | Island of Lindisfarne, Northumberland, England |

| Contributor(s) | Scribe & Illustrator : Eadfrith of Lindisfarne aka Saint Eadfrith Translator & annotator: Aldred aka Aldred the Glossator Binders: Æthelwold (bishop of Lindisfarne) & Billfrith |

| Language(s) | Latin Translated & annotated into Old English (Anglo-Saxon) |

| Source | British Library, Western Manuscripts, Cotton MS Nero D IV 🔗Link to digitized version |

| Physical description | Parchment, 1 volume, 259 ff. [365×275 mm.] |

| Provenance | Durham Cathedral Robert Bowyer (c. 1560–1621) Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1570/71 – 1631) British Museum British Library |

Introduction

The Gospels narrate the story of Jesus, comprising the Gospels of Saint Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Its typographies, illustrations, and specific jewelry embroideries demonstrate various influences from Byzantine era, as well as the Hiberno-Saxon style, which is rooted in early Celtic and Anglo-Saxon traditions.1

The Island of Lindisfarne & historical background

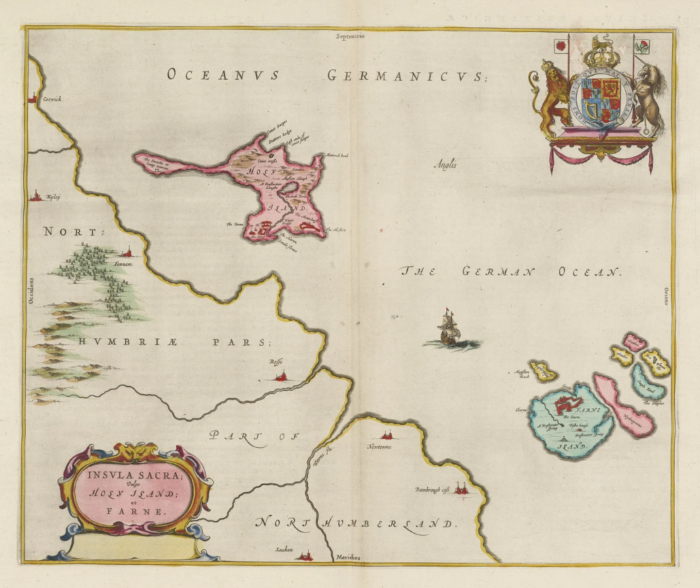

The wild beauty of the coastline surrounding the Lindisfarne Gospels hints at its legendary charm. This island, located six miles away from Newcastle, remains isolated from the hustle and bustle of the mainland even today. The Holy Land holds the historical significance of being the birthplace of one of the most celebrated decorated bible manuscripts in the world. The name Lindisfarne Gospels came from the name of the island and the monastery.

An old map of Lindisfarne (c.1645) © Sanders of Oxford

The story begins when Saint Aidan, along with a couple of Irish monks, settled in the “Holy Land” of Lindisfarne by the order of King Oswald of Northumbria (c. 604-642). According to Priest Aldred’s identifications, the decorated Gospels were created by Bishop Eadfrith at the Holy Island monastery in honor of Saint Cuthbert. It is estimated, with the assumption of additional notes by Priest Aldred on parchments between 950 and 970, that the Lindisfarne Gospels were written around 700 CE2.

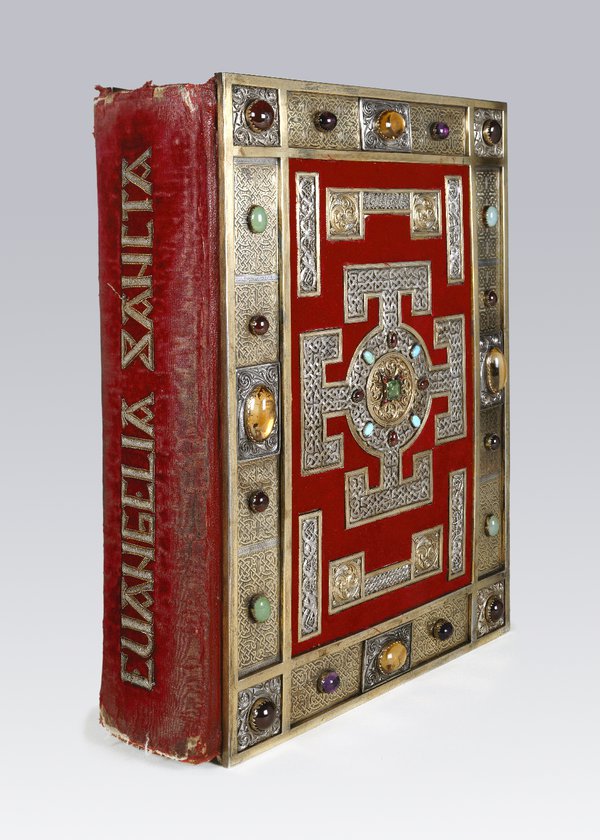

Old and New Bindings

The first leather binding was crafted by Bishop Ethelwald (d. 740), who is closely associated with Saint Cuthbert himself. Additionally, the outer covering of gold, silver, and gemstones was likely added in the middle of the 8th century by Billfrith the Anchorite. Both covers have long since vanished as a consequence of Vikings attack (793) but the manuscript itself has survived. In 1852 a new binding was commissioned by bishop Edward Maltby; Smith, Nicholson and Co. (silversmiths) made the binding with the intention of recreating motifs in Eadfrith’s work.3

©Laing Art Gallery

Analysis of the text

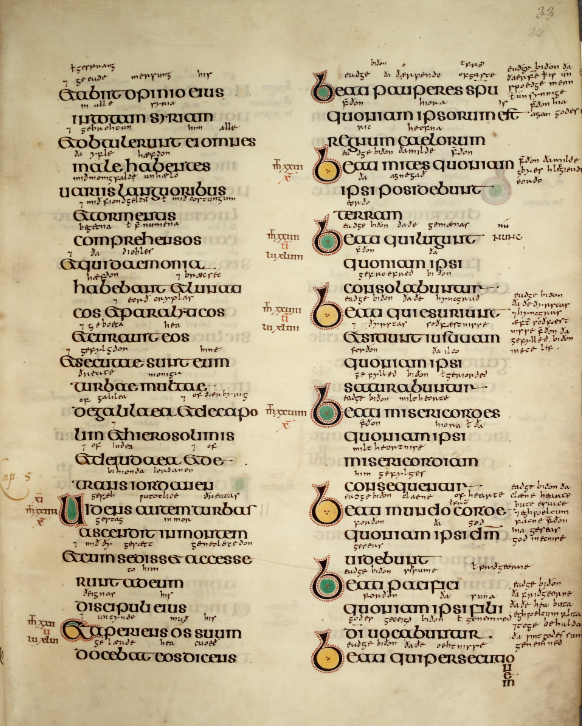

Lindisfarne Gospels consist of the four gospels–Matthew, Luke, Mark, and John. The text is copied from St. Jerome’s Latin translation of the Christian Bible, also known as the Vulgate.

Aldred inserted Old English translations into the original Latin text in the 10th century, which is celebrated as one of the historical pieces of evidence in the history of English literature4. The text is written in an insular script and is the best documented and most complete insular manuscript of the period.

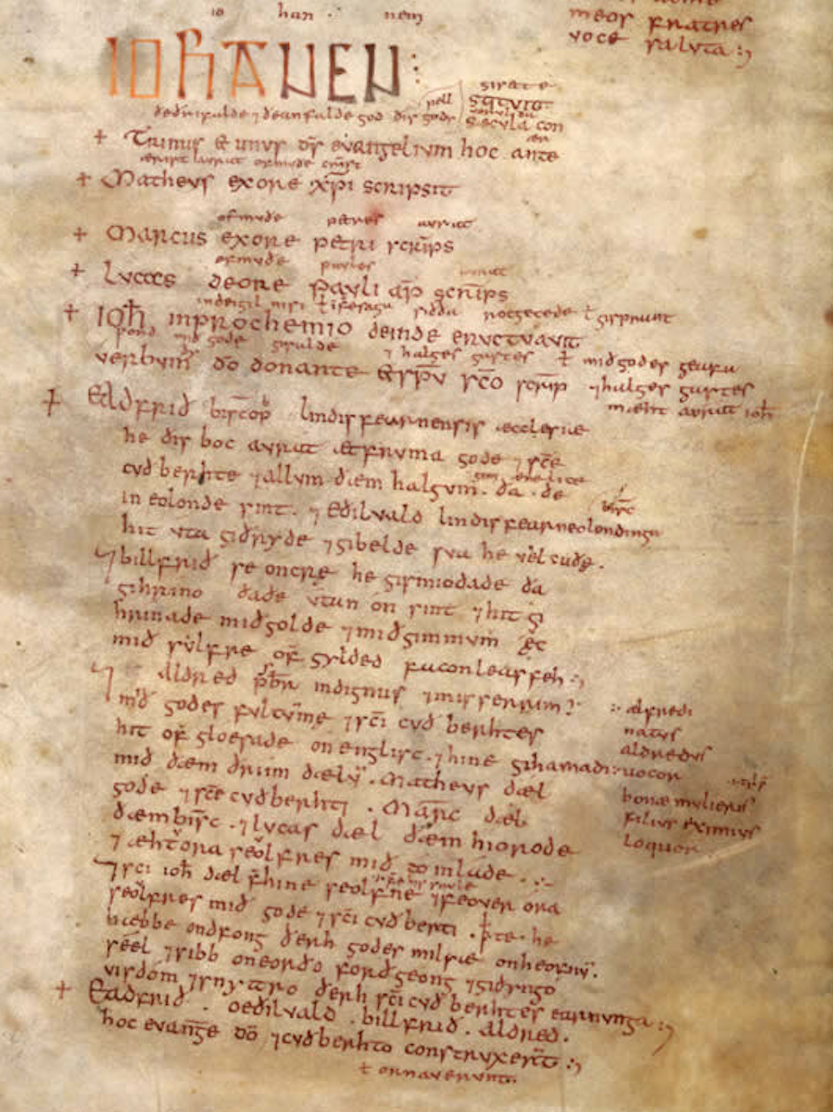

Colophon

The colophon of the Lindisfarne Gospels is placed at the end of the Saint John Gospel. It was written in a rubric and was added to the original scribe around the 10th century by Aldred. The script is an insular minuscule, smaller, and more pointed than the older insular half uncial of the main text. According to Dianne Tillotson, the colophon was recorded in the traditional way. He notes that while it is still debatable whether the contained information is completely accurate from a literature perspective, the colophon reflects how a book was understood in medieval times. That makes it a portentous component of the history of the manuscript. The fact that the colophon was written over 200 years after the original text of the gospel may weaken it as a precise historical fact.5

Analysis of the illustrations

The Gospels contain various alluring illustrations. At the beginning of the Gospel, we encounter an illustration of Matthew, with his head surrounded by an angel, depicted in linear perspective on a sofa. This representation of Matthew’s symbol incorporates a multitude of cross-cultural references from his time.

As we observe the illustration of Matthew, it possibly alludes to the naturalism of Rome and Ancient Greece, especially when compared to the frescoes of the dramatic author Menander (c. 342-c. 292 BCE) in Pompeii, Italy. Furthermore, it is likely that this image either was influenced by or influenced the representation of Ezra in the Vulgate Bible Codex Amiatinus. This particular codex was created in Northumberland between 690 and 716, a date extremely close to the period when the Lindisfarne Gospels were being produced67. We can observe similarities in terms of colors, the position of their feet and pens, and even their sandals. However, unlike Ezra’s voluminous figure and intense colors, Matthew’s portrayal is more flattened, stylized, and slender.

Portrait page, Evangelist Matthew, Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IV_f025v

Ezra’s portrait, Codex-Amiatinus_Old_Testament_folio_5

Fresco_House_of_Menander, Archaeological Park of Pompeii, Italy

Carpet Page of Books of Kells and Lindisfarne Gospels

The Gospels consist of various elements that serve as powerful examples of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship, reflecting a diverse range of designs and forms. Spirals and knots adorn the surface of the carpet page, creating intricate patterns of swirls and vivid colors. When examining the carpet page of Matthew, the symmetrical decorations, geometric patterns, and calligraphy evoke the imagery of a Persian carpet.

Another noteworthy aspect is the similarity of these shapes to archaeological findings in the Celtic region, particularly the well-known Sutton Hoo gold belt from the 7th century. It is estimated that the artists used unparalleled craftsmanship to create these remarkable images8. The carpet decorations bear a resemblance to the designs found in the Book of Kells (c. 800) and the Book of Durrow (c. 680)9. The carpet page of Matthew in the Lindisfarne gospels and in the Book of Kells can be seen below.

Contemporary cultural & political significance

There has been a campaign since 199810 to “bring back the gospels home”. Campaigners have long said that the manuscript should come back to the North East permanently, with a number of locations as options including Durham Cathedral. Supporters include the Bishop of Durham, and the Northumbrian Association.

The gospels were appropriated by Henry VIII during his Dissolution of the Monasteries and they reached the British Library as a part of the Cotton collection. The British Library time and again reaffirmed the Lindisfarne Gospels are to remain in London, despite ongoing calls to return them to the North East citing the reasons it has a legal obligation, as well as the expertise, to look after the work.11

Conclusion

The Lindisfarne Gospels are a treasure that provides a window into the early culture of ancient artifacts and the multicultural life of early medieval society without geographic boundaries. Every aspect of the book, from illustrations to its artifacts and decorations, offers multidimensional references, cross-cultural relationships, and the daily life of early Christianity in the Anglo-Saxon world. Moreover, Lindisfarne offer insights into commercial activities, education, and religious interactions in the Mediterranean.

In conclusion, as bishops embarked on voyages through the Mediterranean and expanded their horizons, they provided contemporary observers with glimpses of early examples of cosmopolitanism during the medieval age, as beautifully depicted in these illustrations. Lindisfarne Gospels is a book that will continue to be admired by people of various cultures for many centuries and will be passed down to future generations.

Bibliography

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2014, August 20). Lindisfarne Gospels.

Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lindisfarne-Gospels ↩︎ - Brain, J. (2021, March 8). The lindisfarne gospels. Historic UK. Retrieved October 31, 2023,

from https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Lindisfarne-Gospels/ ↩︎ - Backhouse, J. (1981). The lindisfarne gospels. Phaidon.

↩︎ - Brain, J. (2021, March 8). The lindisfarne gospels. Historic UK. Retrieved October 31, 2023,

from https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Lindisfarne-Gospels/ ↩︎ - Tillotson, D. (2014, March 21). Lindisfarne Gospels, late 7th century (British Library, Cotton Nero DIV, f.259). Mediaeval writings. https://medievalwritings.atillo.com.au/exercises/colophon/colophon.htm

↩︎ - Wikipedia. (2023, September 4). Codex amiatinus. Wikipedia. Retrieved October 31, 2023,

from https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Amiatinus ↩︎ - Norman, J. M. (2014, August 24). The codex amiatinus: The earliest surviving complete Bible

in the Latin Vulgate, containing one of the earliest surviving images of bookbindings and a

bookcase. Jeremy Norman’s HistoryofInformation.com. Retrieved October 31, 2023,

from https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=226 ↩︎ - British Library. (n.d.-b). Sutton Hoo Gold Belt Buckle. British Library. Retrieved October 31,

2023, from https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/sutton-hoo-belt-buckle ↩︎ - Wikipedia. (2023b, September 14). Book of Kells. Wikipedia. Retrieved October 31, 2023,

from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Kells ↩︎ - Parliament of UK. (1998). Parliamentary business. Parliament UK. Retrieved November 26, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20120310190009/http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.com/pa/ld199798/ldhansrd/vo980402/text/80402-20.htm (archived website) ↩︎

- Lindisfarne Gospels to stay in London, reaffirms British Library after latest North East Exhibition. Sunderland Echo. (2022, December 10). Retrieved November 26, 2023, from https://www.sunderlandecho.com/news/people/lindisfarne-gospels-to-stay-in-london-reaffirms-british-library-after-latest-north-east-exhibition-3949405

↩︎