Saincte Bible by Jacques Corbin

Saincte Bible by Jacques Corbin

by Alister Aldridge

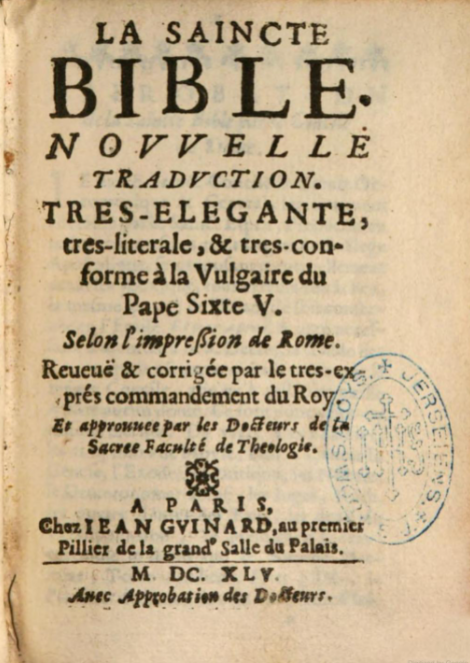

Although the 16th-century was considered as the century of the wars of religions not only in France but also throughout Europe, the 17th-century was also a time of extreme religious and political tensions. Its first half was especially scarred by the Thirty Years War, the last of the great European wars of religions1. Lasting from 1618 to 1648, the Thirty Years War was in fact an agglomerate of conflicts over political and religious motivations (the two always being tied together) between European powers. Europe faced many religious struggles which were both the results and the continuation of the Protestant Reformation. Unsurprisingly, this time was a fertile ground for religious and theological thinking, debate, and production. It was in this context of international and domestic religious conflict that an umpteenth Bible was edited. In 1642, Jacques Corbin, a French lawyer, published his own traduction of the Bible with the support of King Louis XIII (r. 1610-43).

La Saincte Bible – Novvelle tradvction tres – elegante, tres-literale, &tres-conforme à la Vulgaire du Pape Sixte V.

Selon l’impreßion de Rome.

Reueuë & corrigée par le tres-exprés commandement du Roy.

Et approuuee par les Docteurs de la Sacree Faculté de Theologie.

A Paris,

Chez Iean Gvinard, au premier

Pillier de la grande Salle du Palais.

M. DC. XLV.

Avec Approbation des Docteurs.

- Author: Jacques Corbin

- Title: La Saincte Bible – Novvelle tradvction tres – elegante, tres-literale, & tres-conforme à la Vulgaire du Pape Sixte V. Selon l’impreßion de Rome. Reueuë & corrigée par le tres-exprés commandement du Roy. Et approuuee par les Docteurs de la Sacree Faculté de Theologie.

- Date: 1645 (1643).

- Editor: Jean Guinard, Paris.

- Content: In 8 volumes, as follows:

- I: Les V. Livres de Moyse, Genese, Exode, Levitiqve, Nombres, Devteronome.

- II: Iosué, Les Iuges, Ruth., I.II.III.IIII. Livres des Rois.

- III: Premier et Second Livre du Paralipomenon, Premier et Second Livre d’Esdras, Tobie, Iudith, Esther.

- IV: Iob, Pseaumes, Proverbes, Ecclesiaste, Le Cantique des Cantiques, La Sapience, L’Ecclesiastique.

- V: Isaie, Ieremie, Baruch, Ezechiel

- VI: Daniel, Les XII Petits Prophetes, I.II. des Machabees.

- VII: Le Nouveau Testament de N. Sauveur & Redempteur Iesus-Christ :

- L’Evangile selon S. Matthieu, S. Marc, S. Luc, S. Iean.

- Les Actes des Apostres

- Les Epistres de S. Paul aux Romains

- I. II. aux Corinthiens

- Aux Galates

- Aux Ephesiens.

- Aux Philippiens

- Aux Colossiens

- I.II. Aux Thessaloniens.

- I.II. A Timothee.

- A Tite

- A Philemon

- Aux Hebreux

- Epistre de S. Iacques

- I.II. de S. Pierre

- I. II. III. de S. Iean, de S. Iude.

- Apocalypse de S. Iean.

- VIII: Second Tome du Nouveau Testament :

- Les Actes des Apostres

- Les Epistres de S. Paul aux Romains

- I. II. aux Corinthiens

- Aux Galates

- Aux Ephesiens.

- Aux Philippiens

- Aux Colossiens

- I.II. Aux Thessaloniens.

- I.II. A Timothee.

- A Tite

- A Philemon

- Aux Hebreux

- Epistre de S. Iacques

- I.II. de S. Pierre

- I. II. III. de S. Iean, de S. Iude.

- Apocalypse de S. Iean.

- Language: French

- Source: Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon – Collection Jésuite des Fontaines – Digitized by Google.

- Link to the Book of Psalms

- Link to the first volume where the Approvation de la Saincte Bible par le Concile de Trente and l’Approbation de la présente traduction can be found

Purpose: general context of the time of Corbin’s translation

As mentioned in the introduction, tensions were high both in a European and a French domestic context. When Jacques Corbin began his translation of the Bible, circa 1641, the kingdom of France was in an armed conflict against other Catholic powers. On one side, the King had very strained relations with the Huguenot party within his own lands, which had even led to armed rebellions in the 1620s. On the other, his policy during the Thirty Years War attracted the ire of many French Catholics for Louis XIII decided to side with the Protestant powers. Indeed, even though France’s involvement in the war preceded its formal entry in the conflict in 1635, through diplomatic means, the most Catholics of the Catholics could not accept this raison d’Etat and the monarch siding with religious enemies2. The end of the 1630s and the first years of the following decades are marked by important wins against the Imperial side of the war and by 1643, the worsening health of Louis XIII put aside, the European affairs seemed to be going rather well for the French with the “talks of Westphalia” about to start.

Although one should never consider wars of religions to be solely about questions of beliefs, it is not without reasons that one may consider the first half of the 17th-century as a continuation of these conflicts that so deeply marked the previous century. The situation in France and in Europe led to the proliferation of religious writings. Among these writings, both Catholics and Protestants published many editions of the Bible in different languages. During the 16th and 17th centuries in France, the Protestants published various Bibles that had a long lasting influence. Among them were Lefèvre d’Etaples’ (1530), Olivétan’s (1535) or the Bible de Genève (1562 or 1588). The latter is not to be confused with the Geneva Bible in the English language. There were numerous other publications, up to the revised version of the Bible de Genève by the Calvinist Giovanni Diodati in 1644. On the Catholic side, there were notable translations as well. Notable because translation meant written French instead of Latin or Greek, which was not always to the taste of Church authorities. François Véron, adept of many controversies, and the abbot Michel de Marolles (1649) were among these important translators. Another important aspect of Catholic translations was the role played by universities. In 1566, René Benoist, a doctor of theology at the Sorbonne published his own translation. He was supported by the theologians of Louvain but not by his peers at the Sorbonne on the ground that Benoist was too heavily influenced by the Geneva Bible3. Benoist’s Bible was condemned by the Church. However, in 1578, in Antwerp, Plantin published a revised version which was accepted, omitting all mention of Benoist. This Bible printed by Plantin became known as the Bible de Louvain which, once again, has to be differentiated from the eponymous edition of 1550. Theologians from the university of that city were behind this edition which tried to bring the holy scriptures to the “common people” while keeping them away from the attractiveness of Protestant editions and writings.

Jacques Corbin and his translation of the Bible

Jacques Corbin was born in Berry in 1580 and he died in Paris in 1653. He was a lawyer by trade and a member of the Parlement de Paris. Alongside his legal practice, he became a member of the French queen Anne of Austria’s household. He held the office of Master of Requests. During his free time, Corbin started to write. He wished to become a famous writer, although he would prove to be relatively poor in that regard. Nevertheless, he kept on writing poetry4, panegyrics5, and historical works6. It must be noted that Corbin never was a clergyman. His works never brought him real recognition during his lifetime or after his death. According to Bouillet and Chassang, he was even mocked by Nicolas Boileau in his Art Poétique. In their Dictionnaire universel, the formers called Corbin an “obscure writer”7. Writing novels and poetry was one thing, but Corbin intended to make a name for himself and started to write about religion. It proved to be a very negative move for his reputation. In 1620, he was noticed for a pamphlet called Preuve du Nom de la Messe which was controversial. Thus, when he assumed the task of translating the Bible, he already had a negative image among theologians9.

Formal aspects

Jacques Corbin’s Bible is noticeable in the sense that it is unremarkable. The unillustrated Corbin Bible was a translation of the Vulgate. The Vulgate was considered by the Roman Catholic Church as the sole acceptable version of the Holy Scriptures. It was originally written in the 4th century A.D. by Jerome of Stridon. The Vulgate was largely altered over the course of the centuries. Thus, in the 16th century, within the context of the religious tensions originating from the Reformation, the Church and Council of Trent asked for a revised version. It was acted through a papal bull by Clement VIII in 1592. This new version is known as the Vulgata Clementina and served as the official edition until the 20th century. According to Henry Cotton, Jacques Corbin made a very literal translation of the Bible. The author also very much positioned himself in the continuity of the wishes of the Church by stipulating in the title that his translation is “very faithful to the Vulgate of Pope Sixtus V”. Indeed, Sixtus was Clement’s predecessor and the Holy Father who ordered a revised edition of the Vulgate.

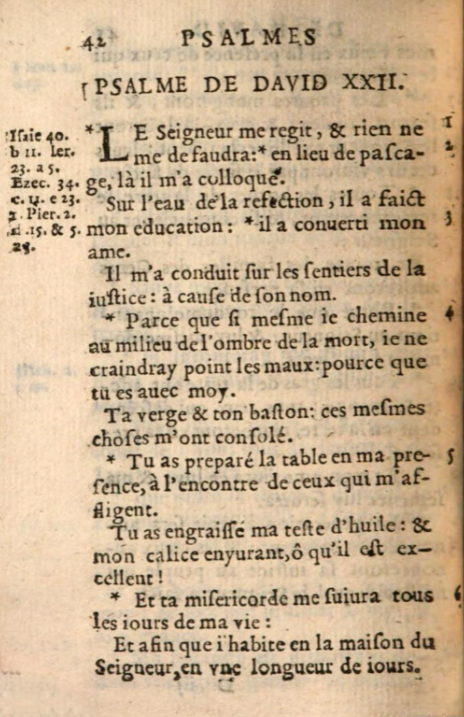

Le Seigneur me regit, & rien ne

me defaudra :* en lieu de pascage, là il m’a colloqué.

Sur l’eau de la refection, il a faict

mon education : * il a conuerti mon

ame.

Il m’a conduit sur les sentiers de la

iustice : à cause de son nom.

* Parce que si mesme ie chemine

au milieu de l’ombre de la mort, ie ne

craindray point les maux : pource que

tu es auec moy.

Ta verge & ton baston : ces mesmes

choses m’ont consolé.

*Tu as preparé la table en ma pre-

sence, à l’encontre de ceux qui m’af-

fligent.

Tu as engraissé ma teste d’huile : &

mon calice enyurant, ô qu’il est ex-

cellent !

* Et ta misericorde me suiura tous

les iours de ma vie :

Et afin que i’habite en la maison du

Seigneur, en vne longueur de iours.

———–

Isaie 40. B II. Ier. 23. A 5. Ezec. 34. C. II. e 23. I. Pier. 2. E. 15. & 5. 28.

The Psalter in Corbin’s Bible follows the traditional Greek numbering, or Septuagint. Psalm 22, otherwise known as “The Lord is my Shepard”, represents a good example of the typographical style of this edition.

Political Value and reception of the Bible

Despite receiving king Louis XIII’s support for his translation, Corbin never met the success he certainly hoped for. Among the blows to his work was the lack of support from the Faculty of Theology of Paris. Instead, he received the support of those from the University of Poitiers. One may read on the approbation pages in the first volume that the translation was read and approved by Louis le Vasseur and F. Jean Faix, both doctors in theology in Poitiers. He also gained the support of one of the Sainte-Marthe brothers, Louis Scévole, both historians considered humanists.

The question that remains is why Corbin did not obtain the support of the Sorbonne. One may venture to say that the Bible was a literary failure. The translation was very literal and Corbin, who did not understand Greek, may have used several other editions in both French and Latin to make his own translation. The style also has the reputation of being pompous and unenjoyable to read. The title itself let one foresees that Corbin considered his writing greater than what his contemporaries thought it was. Corbin did not lie that calling his translation “very literal and conformed to the Vulgate”, but it was not appraised as très élégante. But bad writing could not explain the reaction of the Sorbonne. Indeed, the Parisian theologians were extremely severe towards Corbin for they call upon Richelieu, first minister, to take action10. According to Henry Cotton, they requested that he bury the Bible in the sand “as Moses hid the Egyptian whom he had killed”. There could several reasons behind the condemnation of the translation. The doctors accused Corbin of deliberately falsifying the New Testament (Acts 13,2);11. Although Corbin had already been involved in some religious controversies and had a reputation in that regard, it was unlikely done on purpose.

We dare make a hypothesis as to why the Sorbonne had such a reaction. Corbin was not a clergyman but a laic, and so the theologians may have wished to mark their independence regarding royal influence. The relations between universities and the monarchy were strained sometimes. Universities were often the apanage of clergymen and they also represented a very powerful institution within their seat city but also within the kingdom. During the Wars of Religions, the Sorbonne sided with the Catholic League against Henri IV and had to suffer the consequences. There were debates on what degree of independence from royal power universities should have. In 1642, the jurist and strong support of Richelieu, Cardin le Bret, went on to write that it was a prerogative of princes to establish universities since the Antiquity12. Although it was far from being the historical reality, it was an attempt to push the existence of universities in the hands of the sovereign. To that, one may had the European context aforementioned. By condemning Corbin’s Bible, could the Faculty of Paris found a little revenge against a monarchy siding with Protestant powers against the Emperor, a paragon of Catholicism?

Bibliography

- Basdevant-Gaudemet B., (2021) Histoire des facultés de théologie des universités publiques en France, Revue du droit des religions, 11.

- Bouillet & Chassang (1878), Dictionnaire universel d’histoire et de géographie, Hachette, retrieved from https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionnaire_universel_d%E2%80%99histoire_et_de_g%C3%A9ographie_Bouillet_Chassang/Lettre_C

- Corbin, J., (1645), La Saincte Bible – Novvelle tradvction tres – elegante, tres-literale, & tres-conforme à la Vulgaire du Pape Sixte V, trad. Jacques Corbin, Paris, chez Jean Guignard, 1645 (1ère édition 1643), 8 volumes.

- Cotton H. (1863), Memoir of a French New Tatement, in which the Mass and Purgatory are Found in the Sacred Text, Bell and Daldy.

- Gao J.; (2018), Publier pendant les guerres de religon : Roville et les libraires lyonnais, Questes, 38.

- Lebrun, F. (2003), Le XVIIe Siècle, A. Collin.

- Lortsch, D., (1910), Histoire de la Bible française et fragments relatifs à l’histoire générale de la Bible, s.n., retrieved from http://fdier02140.free.fr/histoirebible.pdf