The Biblia Ectypa

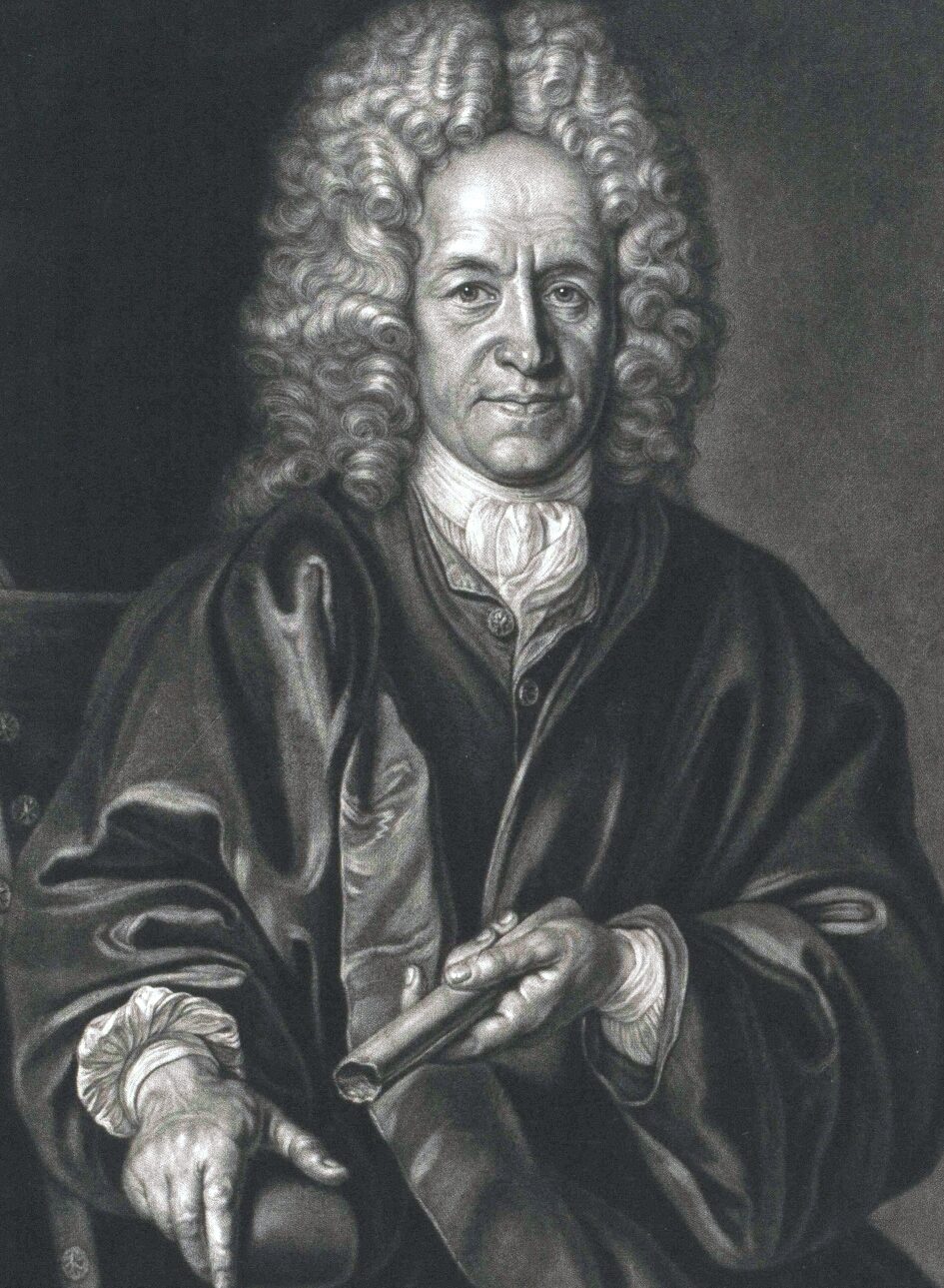

About the Author

Christoph Weigel (1654–1725) was a notable German engraver, publisher, and cartographer. He is best known for his detailed engravings, maps, and illustrated books, which often corresponded to the demands of both artistic and cognitive values. His works are highly valued for their historical and artistic significance.

Undoubtedly his most well-known printed publications are the illustrated Bibles and emblematic books, including his Biblia Ectypa covered here, which stands out as a visual narrative of biblical stories. Abbildung der gemein-nützlichen Haupt-Stände (1698) was a comprehensive book showing different professions and trades in minute detail during the 17th century. In addition, there is Historiae celebriores Veteris [Novi] Testamenti iconibus repraesentatae et ad excitandas bonas meditationes selectis epigrammatibus exornatae (1708), a pictorial and meditative exploration of biblical stories. Weigel also ventured into cartography, creating maps adorned with artistic borders and decorative elements.

Historical Context

The folio-sized Biblia Ectypa was engraved on copperplate. Its roots are in a tradition of picture Bibles, known more properly in Latin as Biblia pauperum, or Paupers’ Bibles, which became extraordinarily popular during the Middle Ages. Many of these earlier Bibles conveyed biblical text and stories with the use of woodcuts, so the contents were not just readable but even accessible to the poor and illiterate classes of society. As its definition implies, the message in these Bibles was intended to be made communicable to such sectors of the population. As a testament to Weigel’s skill, a second edition was published years after his death in 1787.

What distinguished the Biblia Ectypa from an illustrated Bible, where the text takes precedence over the imagery, is the fact that such a picture Bible relied on popular narratives, and the actions of those narratives would unfold in a sequential order. Hence, the medieval receptivity of the Pauper Bible could be transferred to Weigel’s time. In 1666, Weigel departed from his birthplace in Redwig, in the Bohemia region, and from then onward until 1678 lived in Hof, Jena, and Augsburg. From these various locations, Weigel acquired knowledge and experience in different types of engraving. The technique of copperplate engraving took off in southern Germany between the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and also became a major source for the production of biblical illustrations.

Bohemia, southern Germany, Austria, and France are counted among places in which the earliest iterations of woodcuts were discovered, although the bulk are from Germany and simple in their construction. It is clear that pictorial storytelling was not Weigel’s only cultural inheritance. The art form by which stories were crafted that would eventually encompass other materials, such as copper, was also drawn from the cultural milieu of his native Bohemia and where he relocated to in southern Germany. He then continued on with his pursuits in Vienna in 1682, and a year later left for Frankfurt before coming back to Vienna in 1688. Weigel would become known above all for his skill in line engraving as well as in creating mezzotint portraits, which he had done in the last couple decades of his life.

He returned to Augsburg in 1691. The established print culture, artistic heritage, and religious conditions that existed throughout southern Germany ensured that an engraved Bible would enjoy wide dissemination and usage in the area, with Augsburg at the forefront as a historic print capital. After the great success of the Biblia Ectypa, Weigel opened his own print publishing firm with his brother in Nuremberg, settling there in 1697 until his death in 1725.