The Douce Apocalypse

The Douce Apocalypse

by Prince Kumar

| Title | The Douce Apocalypse |

| Contributors | Authors unknown, Latin commentary by Berengaudus |

| Patrons | Edward I of England, Eleanor of Castile |

| Date | 13th Century |

| Language | Anglo-Norman French and Latin |

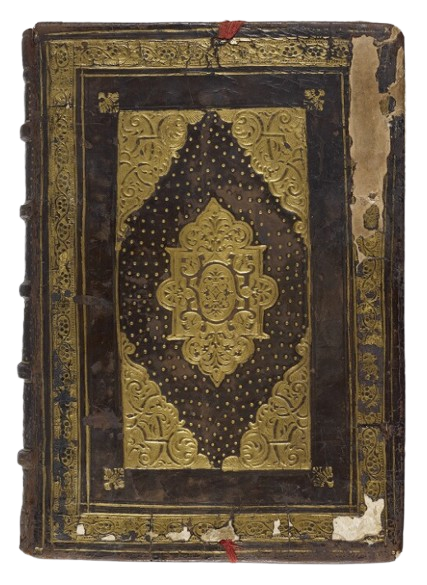

| Dimensions | 310 × 215 mm |

| Origin | Westminster, England |

| Source | https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/d8f4f265-b851-48a8-b324-4fc871f68657/ |

Introduction

The Douce Apocalypse, also known as MS. Douce 180, is an illuminated manuscript of the Book of Revelation—one of the most symbolic and mystical books in the Bible. It is currently preserved in the Bodleian Library of University of Oxford under the reference Douce 180. The manuscript does not have a title page and therefore we don’t know what it was called originally. The current name of the manuscript is derived not from its 13th-century patron, Edward I of England, but from its 19th-century owner, Francis Douce, a London-based antiquarian. It has been described as “one of the glories of English thirteenth-century painting”.

Context

The Douce Apocalypse belongs to a broader tradition of medieval illustrated apocalypses. The apocalypse was a very popular theme in England and France during the 13th and early 14th centuries. Frequent wars, famines, and plagues and most important of all the Crusades led to the beliefs that the end times might be near. This heightened interest in the Book of Revelation reflected the period’s fascination with eschatology—the study of end times and final judgment.

Moreover, illustrating the Apocalypse appealed to medieval illuminators for the spectacular verbal imagery and provided a unique opportunity for visual storytelling. The Apocalypse manuscripts were some of the most frequently illuminated texts of the time, second only to psalters. This prevalence of psalters is attributed to the Benedictine Rule, which required monks to sing the Psalms weekly, necessitating a psalter in every abbey. The Douce Apocalypse stands out for its detailed iconography and use of rich, symbolic imagery.

Specificites of the Douce Apocalypse

The Douce Apocalypse consists of two distinct parts. The first section (ff. 1–12) contains an incomplete version of the Book of Revelation in Anglo-Norman French, along with anonymous commentary, but without miniatures. However, it opens with a large historiated initial within the S of ‘Seint pol’. In its upper part are a knight and a lady kneeling in prayer before the Trinity and bearing the arms of two sponsors of the manuscript: Edward, Prince of Wales and future Edward I of England, and his wife, Eleanor of Castile. The lower part of the image shows St John both as a scribe and as a preacher. The first page also contains an ornamental bar extending to the bottom of the page shows two hunting dogs pursuing a rabbit and a man blowing a horn.

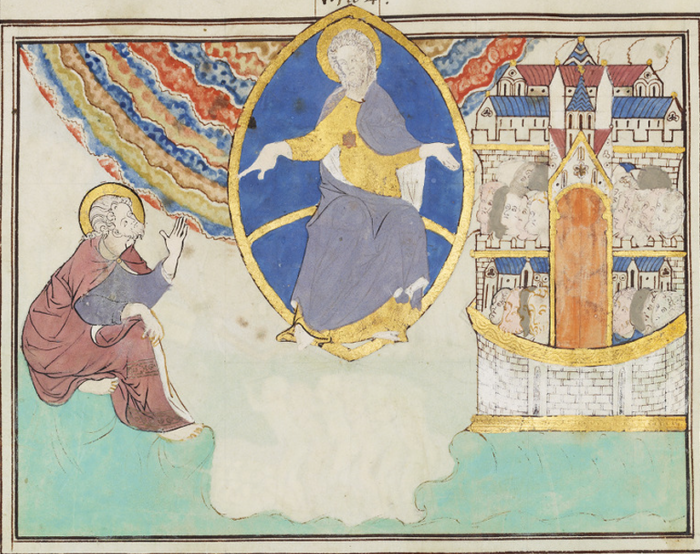

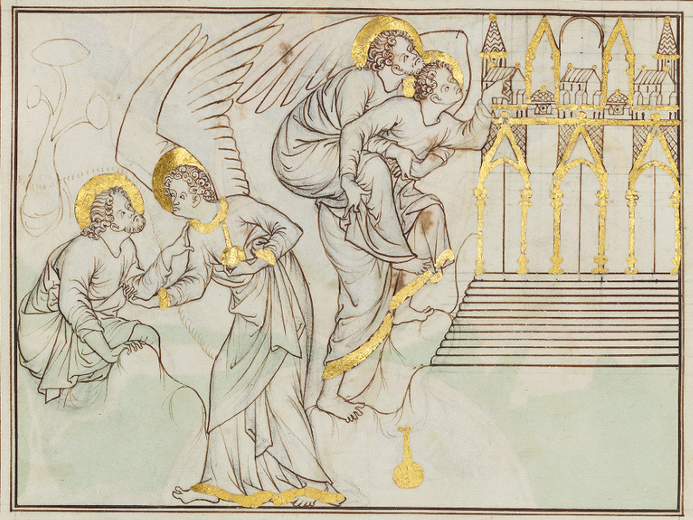

The second part (ff. 13r–61r) includes the same text in Latin with commentary traditionally attributed to a Benedictine monk Berengaudus. Exact whereabouts of Berengaudus are now argued but his commentary was written no later than the 11th century. This second part is richly illustrated, containing 97 miniatures – one on each page occupying half the page. The illustrations remain unfinished and in various stages of completion, some in just daft form. The style of these miniatures is directly influenced by the Parisian style of Saint Louis, suggesting that they may have been produced in the same workshop as BNF MS Lat. 10474. Scholars have identified three distinct artistic styles within this section, suggesting the possible involvement of three different artists.

Illustrations in various stages of completion

Chapter 5 of Book of Revelation

Chapter 5 of Revelation marks a key moment in the Revelation.In Revelation Chapter 5, John sees God on His throne holding a sealed scroll, symbolizing divine knowledge and his plan for the world. An angel proclaims, “Who is worthy to open the scroll and break its seals?” but no one is found worthy, causing John to weep. Then, an elder reassures John, pointing to the Lion of the tribe of Judah—a title for Christ—who has triumphed and is therefore worthy to open the scroll. At this moment, John sees a Lamb standing as though slain, with seven horns and seven eyes that looks like it has been sacrificed yet is alive and powerful. The Lamb approaches the throne and takes the scroll, prompting a scene of worship as the twenty-four elders and four living creatures fall down before the Lamb. The chapter ends with a doxology, as myriads of angels join in praising the Lamb for his worthiness.

Chapter 5 Illustrations

The Douce Apocalypse includes two illustrations specifically depicting the events of Chapter 5 of Revelation. In the first illustration, an angel with a halo and a cross-staff, dressed in blue robes, is gesturing outward, possibly issuing the proclamation : “Who is worthy to open the scroll and break its seals?” This scene also depicts John in a state of distress, as he is saddened and concerned that no one can open the scroll. An elder stands next to John, pointing towards a lion – a symbolic reference to the “Lion of the tribe of Judah,” or Jesus Christ,reassuring John that the Lion has triumphed and is indeed worthy to open the scroll.

In the second illustration, a Lamb with seven eyes stands atop a platform resembling an altar. The Lamb holds a cross-staff with a banner, symbolizing Christ’s victory over death, and stands beside a chalice. Around the Lamb, in four compartments, are groups of six crowned and robed figures, representing the twenty-four elders mentioned in Revelation. In the illustration, the elders are shown in postures of reverence,directing their gaze and gestures toward the Lamb. Their crowns signify their royal or priestly status in the heavenly realm, highlighting the Lamb’s superiority and their recognition of his worthiness.

In the corners of the central frame of the illustration are the four symbolic animals—a lion, an ox, a man, and an eagle—representing the four living creatures described in Revelation. These creatures join the elders in worship, symbolizing all of creation’s recognition of the Lamb’s authority. The presence of these creatures underscores the universal nature of the adoration being depicted.

Bibliography

Binski, Paul. ‘THE ILLUMINATION AND PATRONAGE OF THE DOUCE APOCALYPSE’. The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 94, Sept. 2014, pp. 127–34. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581514000602.

Kelly, Joseph. ‘Review of The Douce Apocalypse: Picturing the End of the World in the Middle Ages, by N. Morgan, and St. Margaret’s Gospel Book: The Favourite Book of an Eleventh-Century Queen of Scots, by R. Rushforth’. Theology & Religious Studies, Oct. 2008, https://collected.jcu.edu/theo_rels-facpub/37.

MS. Douce 180 – Medieval Manuscripts. https://medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/catalog/manuscript_4550. Accessed 28 Oct. 2024.

Stones, Alison. ‘Morgan, Nigel. The Douce Apocalypse. Picturing the End of the World in the Middle Ages & Rushforth, Rebecca. St Margaret’s Gospel Book: The Favourite Book of an Eleventh-Century Queen of Scots’. Textual Cultures: Text, Contexts, Interpretation, vol. 3, no. 1, Apr. 2008, pp. 79–81. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.2979/TEX.2008.3.1.79.