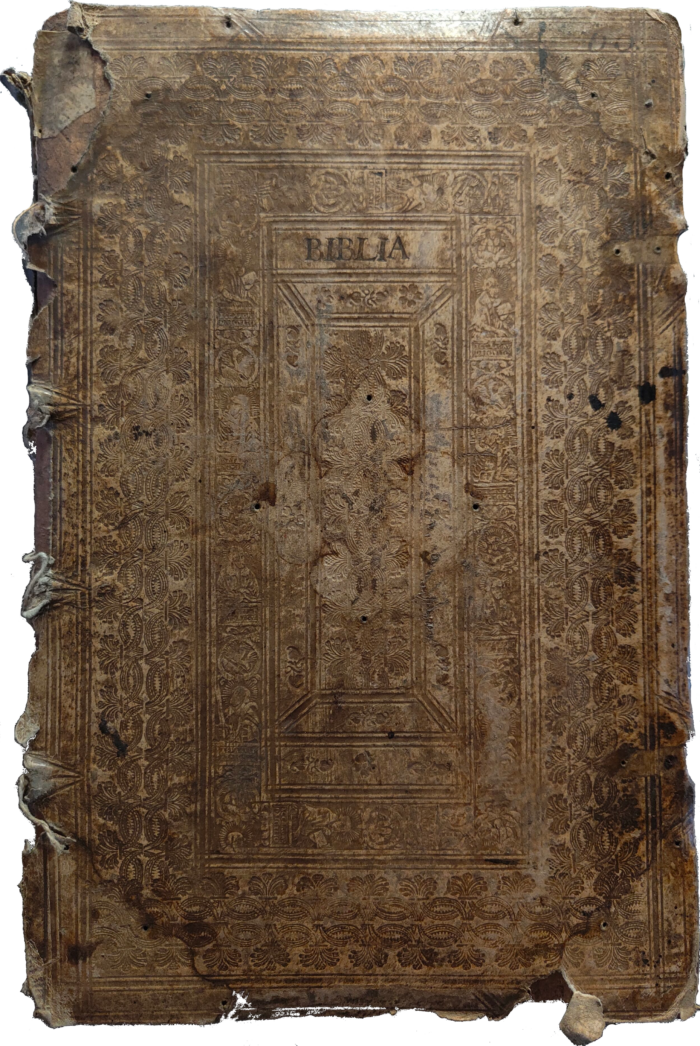

Biblia ad vetustissima exemplaria nunc recens castigata

by Félix Cassand & Cécile Pommier

| Title | Biblia ad vetustissima exemplaria nunc recens castigata : his accesserunt schemata tabernaculi mosaici, templi salomonis, omniumq[ue]; præcipuarum historiarum, summa arte & side expressa. |

| Contributor | Johannes Hentenius (edition) |

| Date | 1566 |

| Place | Frankfurt am Main, Germany |

| Language | Latin | Location | Bibliothèque d’Etude et de Conservation, Besançon |

Printing Tradition

Frankfurt Book Fair

Johannes Gutenberg created moveable type printing in Mainz, located 45 kilometers west of Frankfurt, circa 1450. Frankfurt was a significant commerce hub at the period, bringing together merchants from throughout Europe twice a year to trade bulk goods such as grain and fish, as well as more valuable items like horses, spices, and fabric. Although there were no printers in the town until around 1530, records reveal that the fair of 1478 already contained printer-booksellers, indicating that job opportunities had not yet expanded. In 1498, Aldus Manutius, a well-known printer from Venice, exhibited his firm at the fair. Dutch and French printers likely joined about the same time.

Antique woodcut town view of Frankfurt am Main. Printed in Basle by Heinrich Petri in 1574.

In the 16th century, the book trade at the fair was focused in the “Büchergasse”, or “Book street”, located between the Main River and Leonard’s Church. In the mid-16th century, publishers began declaring their titles for sale in Fair Catalogues. Book historians believe that up to 100 booksellers from various nations set up shop and sold up to 20,000 works, mostly in Latin and German, based on cataloguing and archival documents.

In the 17th century, the German Thirty Years War had a significant impact on the Frankfurt region, resulting in an economic slowdown and a decline in foreign trade. Non-Catholic printers shifted their trade to Leipzig, located about 400 kilometers east and known for its Protestantism.

Leipzig’s book trade focused on northern markets, selling German, Dutch, Swedish, and sometimes Russian titles, but had limited global exposure.

This book fair was the most important one in Germany from the 15th to the 17th century.

Religion in Frankfurt

Throughout the 1550s, 1560s, and 1570s, Frankfurt am Main welcomed Protestant exiles that were French, Dutch, or English. Many of the first refugees were the so-called “Marian exiles”. These exiles were the first Protestants, fleeing Catholic governments. Catholic authorities violently persecuted those who did not attend the mass, forcing early Protestants to choose between martyrdom at home or fleeing abroad. Thousands went to Frankfurt, a self-governing city with some control over religious affairs. There actually was rivalries between the Calvinists (calling themselves the Reformed) and the Lutheran (calling themselves the Evangelical). The refugees were for most of them Calvinists and the Lutheran had a hard time seing people practicing Christianity differenlty. This lead from expulsion to churches to the deny of citizenship and the pastors of Frankfurt incited hostility towards the refugees and demanded that they accomodate to Frankfort religious habits or leave the city.

Image Analysis

John’s vision of the Christ (rev. 1)

To know more about John, click here.

John is sending visions through letters from Patmos to the seven churches, all located in Asia Minor: Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia and Laodicea. This is a literal interpretation of this first chapter. First thing to notice are the clouds that are on the edges, creating a frame around the scene (“venit cum nubibus”, 1:7). It gives an ethereal mood to the picture. Second element are the seven golden lampstands (“septem candelabrorum aureorum”, 1:13). Those lampstands represent the seven churches to whom the man is talking. There are almost as big as the man, and takes a huge part in the scene. In the middle, a man is holding seven stars in his right hand (“et habebat in dextera sua stellas septem”, 1:16) and has a sword coming out of his mouth (“similem hominis vestitum podere, et praecinctum ad mamillas zona aurea”, 1:13). This man is in the center place, seems tall and is represented as magnificent. In the text, John describes how he fell in front of this great figure. Therefore, the drawing represents the man standing on the back of John. He is venerating and puts the man in a higher position. This image is definitely positive towards the text, and gives a very literal idea to the reader.

The throne in Heaven and the scroll and the lamb (rev. 4-5)

The two parts of the revelation 4 and 5 are represented at the same time, with different elements. After the spirit charged John to warn the seven churches to repent in exchange for glory (rev. 2-3), the revelation 4 is describing the man facing twenty-four elders, surrounded by the seven churches and four living creatures. The image is again very literal. It follows the same principle as the first one. In the middle, the man is standing on a throne (“et statim fui in spiritu: et ecce sedes posita erat in caelo, et supra sedem sedens”, 4:2). He is again, on the top middle part of the image. It emphasizes the importance of the character. Surrounding him and the throne, a circle represents a rainbow: “et iris erat in circuitu sedis similis visioni smaragdinae”, 4:2). The twenty-four thrones that faces the spirit are represented by one man, with a crown on his head (“Et in circuitu sedis sedilia viginti quatuor: et super thronos viginti quatuor seniores sedentes, circumamicti vestimentis albis, et in capitibus eorum coronae aureae”, 4:4). It is a choice to represent only one man will be explained by reading and analyzing the chapter five. The seven lampstands are positioned above the man and the rainbow, which are now the seven spirits of God: “et septem lampades aredentes ante thronum, qui sunt septem spiritus Dei” (4:5). This follows the lampstands of the first image. Then, four creatures are also around the man, but look different than in the text. Indeed, even though the creatures look the same: there is a lion, an ox, a man and a flying eagle (4:7), the only difference with it are their eyes, they are not covered of it like in the text. A hypothesis would be that stylistically, it is easier and much more readable to not represent that particular aspect.

As said earlier, the second image also represents revelation five. Indeed, on the spirit’s legs, there is a scroll with seven seals: “et vidi in dextera sedentism supra thronum, librum scriptum intus et foris, signatum sigillis septem” (5:1). In the text, it is said that no one is able to open the scroll, except for the lamb who represents Jesus in the religious imagery. It is common to represent it with the throat cut. Maybe, as the many eyes for the four creatures, the illustrator did not want to add gore elements. When the lamb is opening the scroll, everyone in the scene is supposed to fell in front of the lamb and the spirit. Therefore, the image represents John and the creatures praising, but also the twenty-four elders playing the harp: “et cum aperuisset librum, quatuor animalia, et viginti quatuor seniors ceciderunt coram Agno, habentes singuli citharas, et phialas aureas plenas odoramentorum, quae sunt orations sanctorum” (5:8). The scene takes all of its interest, it is not just a man on a seat like for chapter four. It is now a whole crowd that is praising.

Compare to the first image, this one is much more complex. It has a lot of different elements from the two chapters. Even if it is represented very literally, with the spirit on the throne, the lampstands, the four living creatures, the lamb and the scroll, the twenty-four elders with their harp and John, two elements appear to be changed. First, the creatures are not covered with eyes. Second, the lamb does not have its throat cut. Everyone is around the throne, which gives an impression of magnificence and importance to the image.

Bibliography

For the translation of the Bible, we used: https://www.biblegateway.com/

Jean HADOT. APOCALYPSE DE JEAN [en ligne]. In Encyclopædia Universalis. Disponible sur : https://www-universalis-edu-com.scd1.univ-fcomte.fr/encyclopedie/apocalypse-de-jean/ (consulté le 13 novembre 2024)

Antoine LAPORTE. FRANCFORT-SUR-LE-MAIN [en ligne]. In Encyclopædia Universalis. Disponible sur : https://www-universalis-edu-com.scd1.univ-fcomte.fr/encyclopedie/francfort-sur-le-main/ (consulté le 13 novembre 2024)