The Bamberg Apocalypse

The Bamberg Apocalypse

by Cindy Bellamy

| Title | The Bamberg Apocalypse |

| Contributors | John the Evangelist. Anonymous scribes and illuminators at Reichenau Monastery. Commissioned by Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor. |

| Date | circa 1010 |

| Place | Produced in the Scriptorium of the Reichenau Monastery, and is now in the Bamberg State Library. |

| Language | Latin Vulgate |

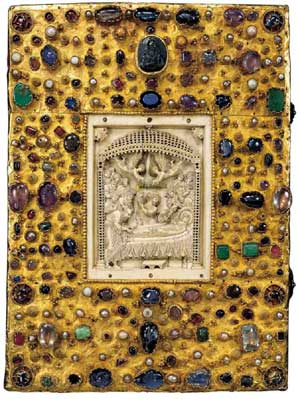

The Revelation to John: In this Bamberg Apocalypse illuminated miniature, the Son of God hands the Book of Revelation to John, symbolising divine inspiration.

The Bamberg Apocalypse, created circa 1010 at the scriptorium of the Reichenau Monastery, stands as a masterwork of medieval illumination and political symbolism. Commissioned during a pivotal moment in Holy Roman Empire history, this richly illustrated Latin Vulgate manuscript was likely to have been ordered by Emperor Otto III for personal use. It later passed to Henry II, who, with his wife Cunigunde, gifted it to the Abbey of St. Stephan in Bamberg. The manuscript remained a prized treasure of the Abbey for centuries, and following the secularisation of church properties in the early 19th century, it was transferred to the Bamberg State Library.

More than a holy text, the Bamberg Apocalypse embodies the political and religious aspirations of the Ottonian dynasty. The manuscript, which Otto III probably used for personal reading and religious observance, reflects his ambition to unite his empire under divine sanction. Alongside the Apocalypse of St. John, the manuscript also includes an evangelistary, indicating its use not only for private devotions but also in liturgical settings, such as feasts and choral prayer. Through 57 illuminations and a distinctive blend of Byzantine, Carolingian, and Romanesque styles, the work visually communicates the cultural and religious unity Otto III sought to foster. Its vivid iconography, with gold backdrops and classical architectural elements, illustrates John the Evangelist’s apocalyptic visions and the imperial grandeur Otto III envisioned for his empire, drawing on the legacy of both Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine influence of his parents, Otto II and Theophanu.

Image attribution: Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image attribution: Sémhur derivative work: OwenBlacker, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Some examples of Ottonian Art.

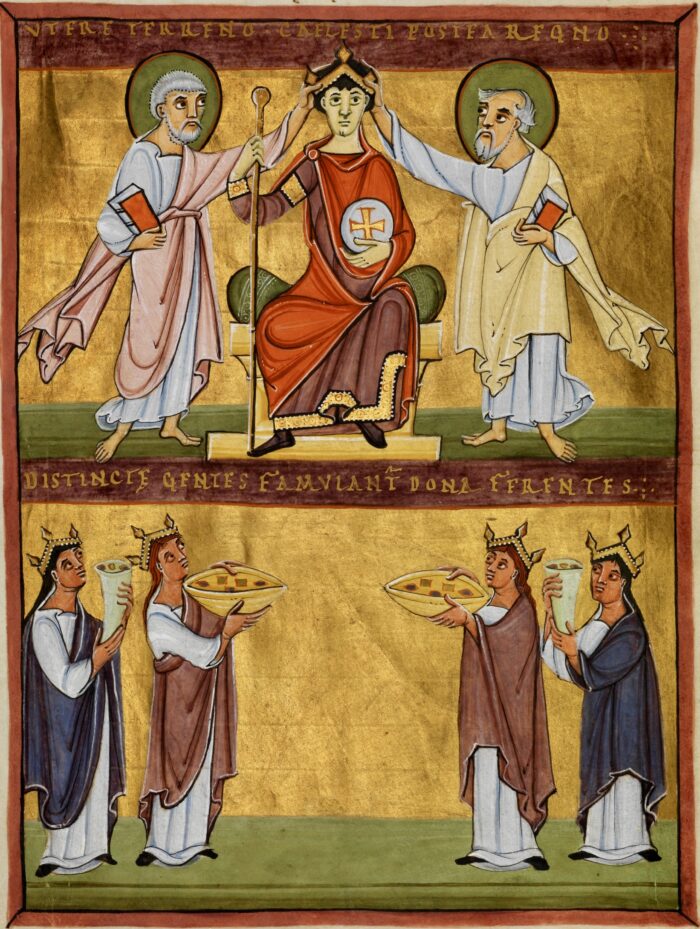

The imagery in the final two miniatures of The Bamberg Apocalypse conveys clear political, moral, and theological messages. In Folio 59 verso, we see Emperor Otto III seated on his throne, facing forward in a richly decorated robe, with short dark hair, a rod sceptre in one hand, and a white orb marked with a golden cross in the other—a symbol of divine authority. Saints Peter and Paul flank him, gently touching his crown as if to confirm his divine right to rule, visually proclaiming his regency. The inscription above reads: UTERE TERRENO. CAELESTI POSTEA REGNO (‘Use the earthly; thereafter, the heavenly kingdom’).

Beneath the ruler, four crowned women, each representing a different nation, present offerings of bowls and cornucopias of precious stones. This gesture signifies both allegiance and tribute from the peoples of the earth. The central inscription reinforces this idea: DISTINCT(A)E GENTES FAMULANT(UR) DONA FERENTES (‘Distinct nations/families serve, bearing gifts’).

Folio 60 recto, known as The Triumph of Virtue Over Vice, portrays virtues defeating vices. In the upper and lower sections, we see white-veiled women, representing virtues, standing on defeated, bare, helpless female figures symbolising vices. Each virtue holds a male figure, likely symbolic of biblical figures—perhaps Obedience with Abraham and Chastity with Moses in the upper part, Penitence with King David and Patience with Job in the lower. The inscriptions, IUSSA D(E)I CO(M)PLENS. MUNDO SIS CORPORE SPLENDENS (‘Following God’s command, be pure in body’) and POENITEAT CULPAE. QUID SIT PATIENTIA DISCE (‘Repent of guilt; learn what patience is’), further reinforce a moral imperative.

The bold, gilded backgrounds and stylised, symbolic gestures create a visual language typical of Ottonian manuscript illumination, where form and colour emphasise the divine over the earthly. This deliberate, non-naturalistic minimalism heightens the sense of an otherworldly, spiritual realm and aligns with Byzantine influences on Ottonian art. Saturated colours, especially gold leaf, and simplified, hieratic compositions visually assert Otto’s rule as divinely sanctioned political authority. Through these scenes, The Bamberg Apocalypse does more than illustrate biblical visions; it enacts an Ottonian vision of a divinely guided empire, where rulers embody earthly power and spiritual authority that was typically characteristic of medieval rulers.

Exploring Chapter 13

Around the year 1000, Europeans took seriously the possibility that an apocalypse might be near. Apocalyptic narratives in the Bible, especially one that promised salvation at the end of time as in John’s revelation, provided a sense of reassurance. Although apocalyptic stories were not new, they often reflected an adaptation of pre-Christian mythologies, incorporating familiar elements from them.

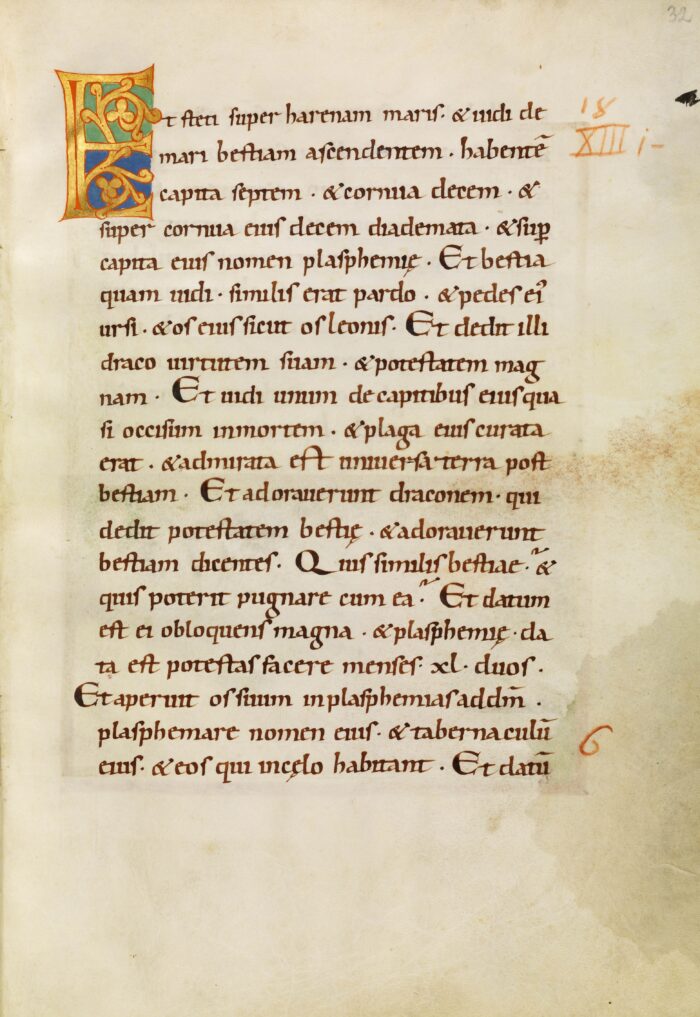

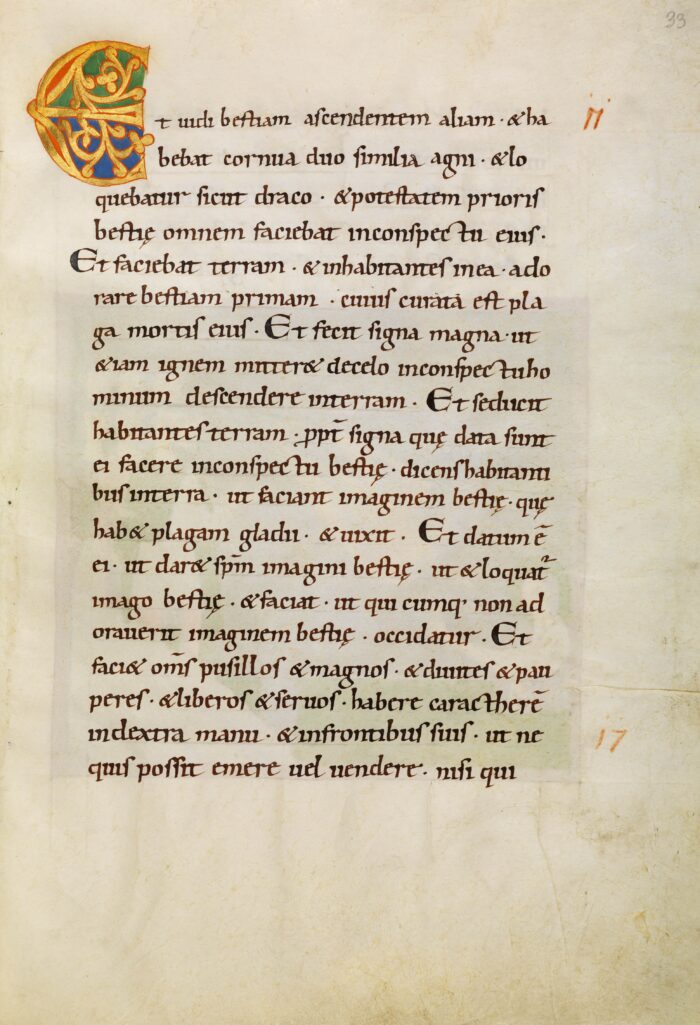

Bamberg Apocalypse pages from chapter 13

Click here for transcription and translation

Click here for transcription and translation

Click here for transcription and translation

Click here for transcription and translation

The biblical Apocalypse, the Book of Revelation, written by John the Evangelist c. 8 – c. 100 AD (also known as John of Patmos), incorporates themes from the Book of Daniel, a 2nd century BC biblical apocalyptic story. John adapts these and other elements to address the political, sociological, and religious circumstances of his time. Chapter 13 contains many symbols that would have had specific meanings for John, some of which I will delve into here. Although Patmos was far removed from Reichenau and a millennium separated their respective contexts, mythological symbols were often deeply embedded in European cultures and lingered for millennia. These symbols may have played a role in transmitting and absorbing new religious stories across time and space, along with the international language of Latin Vulgate in The Bamberg Apocalypse.

John stands behind water as a massive, panther-like beast rises from it. With a lion’s head, bear paws, and a shaggy mane, its body spirals backward. Six dragon heads emerge from its neck, each adorned with pearl-tipped horns. The beast’s appearance, with its seven heads, is reminiscent of seven headed Mesopotamian mythological beasts, some of which appear wounded.

In Chapter 13 of Revelation, we encounter two of the three beasts described in the book: the beast from the sea and the beast from the land. These beasts symbolised chaos in nature and forces of evil reflective of spiritual disarray faced by humankind. They embodied what was morally repugnant and served a dualistic function to moral imperatives within Revelation. The portrayal of these beasts can be understood as illustrating the path toward salvation and the reestablishment of harmony in both the earthly and spiritual realms.

John sees another beast rising from the earth, with lamb-like horns and a dragon’s voice. It wields the authority of the first beast and forces the earth’s inhabitants to worship it.

John, shown as a half-figure, points to a massive winged dragon with ram’s horns emerging between water and land. The beast turns toward seven men who are worshipping its satanic power.

Scholars have suggested that the beast from the land represented political tyranny, while the beast from the sea symbolised economic oppression. This was possibly John’s veiled reference to Emperor Nero, whose persecution of Christians is well-documented. Nero’s reign also involved severe conflicts with the Jewish population, particularly during the Jewish War (66-73 CE)—although direct economic exclusions of the Jews are not as prominently emphasised in historical accounts. The ‘mark of the beast’ (666), inscribed on the heads and hands of individuals, is often interpreted as a perversion of the Jewish prayer in which God blesses the head and hand, connecting them to the divine. The number 666, when considered through the lens of gematria—a mystical Jewish numerology—carries negative connotations, as the number 6 was considered flawed or incomplete, and its repetition three times symbolised a complete inversion of divine perfection. The ‘mark’ allowed individuals to participate in commerce, but it also signified their spiritual doom, as they were not saved in the end. This interpretation could be viewed as a form of ‘revenge propaganda’ aimed at Nero, though no single interpretation has been universally accepted by scholars.

Around 1000 CE, apocalyptic stories circulated widely in Christian Europe, especially within the Holy Roman Empire, assisting in the Christianisation of formerly pagan regions. Despite the spread of Christianity, echoes of pre-Christian beliefs persisted, as those in apocalyptic themes. These included common motifs across the Indo-European world, such as the sea serpent in the Norse apocalypse, Ragnarök, where Thor battles the forces of chaos. Anglo-Saxon and Germanic cultures also depicted cosmic battles between gods and chaos beasts, as seen in Beowulf, reflecting similar themes in Greek, Celtic, and even Zoroastrian traditions.

Jewish apocalyptic traditions, introduced to the Roman world through early Christianity, heavily influenced the end-times narrative in Revelation. These images of chaos beasts and final battles likely resonated with diverse European cultures. Apocalyptic themes and beast symbols can be traced back thousands of years before the writing of Revelation in Mesopotamian religious tradition, which seemed to have spread through oral traditions along trade routes.

In this earlier vision from Chapter 12, the dragon, cast down to earth, pursues the woman sending a flood of water after her. The earth swallows the water, saving her (Rev 12:13-16).

She evades the seven-headed dragon as the earth, depicted as a mound of clods, swallows the flood sent by the beast. This scene also mirrors various pre-Christian mythological beast motifs.

In this brief exegesis of Chapter 13 in The Bamberg Apocalypse, it becomes evident that the apocalyptic imagery of beasts and chaos served multiple purposes. It addressed the Ottonian dynasty’s political and spiritual interests, reinforcing their authority through divine symbols to present a vision of order in a time marked by uncertainty. This approach—using symbols of chaos and crisis to legitimise power—is reflective of a much older narrative tradition. When the Book of Revelation emerged, its motifs were already ancient, with roots stretching back thousands of years into Mesopotamian and other mythological traditions.

This enduring use of crisis narratives—rooted in millennia-old mythologies and pre-Christian stories—illustrates a timeless strategy. These narratives often draw upon fear-evoking images of nature’s power and unpredictability, which would have resonated deeply in an era when the wilderness was a real threat. Yet, a question arises as to whether such narratives serve the collective good or, ultimately, the interests of those who wield them to consolidate ideological power and prompt submission to beliefs or authorities claiming to offer protection.

By considering The Bamberg Apocalypse within this broad cultural context, the manuscript becomes a bridge to a dialogue on humanity’s tendency to use crisis narratives as tools of influence for control and power, as the Ottonian dynasty would have done. An interactive map highlighting beast symbols across geographic regions invites reflection on how these mythological symbols have travelled and evolved over 5,000 years in narratives and physical artefacts. Framed within this cross-cultural comparison, The Bamberg Apocalypse might be one fragment to consider in this context revealing significant insights about humanity.

Beast symbols across cultures

Explore the map to see examples of beast symbols across various mythologies’ stories of apocalypse, chaos, or the ‘underworld,’ often representing forces in opposition to ‘good’ or ‘the divine.’ Notably, a seven-headed beast, similar to those in later apocalyptic narratives, appears in Mesopotamian religion as far back as the Iron Age, as depicted on a metal artefact.

Click here for the Map Image Attribution List.

- Altuna Runestone, Jörmungandr/Midgard Serpent, Bengt A Lundberg / Riksantikvarieämbetet, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Cerberus, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Louvre, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Gosforth Cross, Jörmungandr/Midgard Serpent, Unknown artist. Reproduction by Julius Magnus Petersen (1827 – 1917)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Illuyanka, Ancient City Melid, Georges Jansoone (JoJan), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Jörmungandr/Midgard Serpent, Micha L. Rieser, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

- Lernaean Hydra, Athens, Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Lernaean Hydra, Caere, Getty Center, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Seven headed monster, Assur, Assyria, The Biblical Archaeology Society (BAS)

- Seven-headed serpent, Hazor, Ulrike and Zurkinden, Stamp Seals of the Southern Levant Project

- Seven headed serpent, Tell Asmar, Iraq, Revelation Revolution.

- Tiamat (and Marduk), Nimrud, Temple of Ninurta, Assyria, TYalaA, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Tiamat, Assyria, The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Typhon, Magna Graecia, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Urnes Stave Church carving, Jörmungandr/Midgard Serpent, Micha L. Rieser, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

References

- The Bamberg State Library. (n.d.). The Bamberg Apocalypse, List of all research documentation known by The Bamberg State Library. Zotero. https://www.zotero.org/groups/4950475/staatsbibliothek_bamberg/collections/NYVMKYXC

- Bavarian State Library Digital Library / Munich Digitisation Centre. (n.d.). Book illuminations from the Reichenau Monastery. Collection “Book Illuminations from the Reichenau Monastery” | MDZ. https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/c/e5d21fa6-5fba-4d4a-a243-2a4ef5b7661c/about

- Dahl, J. L. (2024, May 23). Where have all the Ur III seals gone? Avar. https://avarjournal.com/avar/article/view/2851

- Ganz, D. (2021). Richard K. Emmerson, Apocalypse Illuminated: The Visual Exegesis of Revelation in Medieval Illustrated Manuscripts. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale, (256). http://journals.openedition.org/ccm/8786 ; https://doi.org/10.4000/ccm.8786

- De Hamel, C. (2012). A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. Phaidon Press Limited.

- Emmerson, R. (2012, October 2). Bamberg Apocalypse. Grove Art Online. Retrieved November 7, 2024, from https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7002226645

- Emmerson, R. K., & Lewis, S. (1984). Census and bibliography of medieval manuscripts containing Apocalypse illustrations, ca. 800–1500. Traditio, 40, 337–379. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27831161

- Evangelist, J. H. (n.d.). Bamberger Apokalypse – Staatsbibliothek Bamberg Msc.Bibl.140. The Bamberg State Library. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:22-dtl-0000087130

- Gertsman, E., & Rosenwein, B. H. (2018). Christ’s Mission to the Apostles, c. 970–980, Ottonian, Milan, Italy, ivory; 18.20 × 9.90 × 1.00 cm (7 1/8 × 3 7/8 × 3/8 inches). In The Middle Ages in 50 Objects (pp. 18–21). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Google, & The Bamberg State Library. (n.d.). The Bamberg Apocalypse – Google Arts & Culture: All miniatures from the manuscript Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc.Bibl.140. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/lgWhP_Fswg0iLw

- Gäbel, G., Geigenfeind, M., & Müller, D. (2024). Textforschung zu Septuaginta, Hebräerbrief und Apokalypse: Die Relevanz von Textkritik für die Erforschung des frühen Judentums, des Neuen Testaments und des frühen Christentums. Festschrift für Martin Karrer zum 70. Geburtstag. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111549682

- Kamp, H. R. van den, & Peels, E. (2017). Playing with Leviathan: Interpretation and reception of monsters from the biblical world (K. van Bekkum & J. Dekker, Eds.; Vol. 21). Brill.

- Kuder, U., Hicks, C., Exner, M., Mütherich, F., Reinheckel, G., & Little, C. (2003). Ottonian art. Grove Art Online. Retrieved November 7, 2024, from https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000064248

- Latin Vulgate New Testament Bible – Revelation 13. (n.d.). Latin Vulgate Bible. https://vulgate.org/nt/epistle/revelation_13.htm

- Lobrichon, G. (1999). Jugement sur la terre comme au ciel: L’étrange cas de l’Apocalypse millénaire de Bamberg. Médiévales, 37, 71–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43027067

- Nemirovsky, A., Shelestin, V., & Yasenovskaya, A. (2023, November 30). Scene of triumph over the stretched enemy next to an Anatolian SACR… Anatolia Antiqua. Revue internationale d’archéologie anatolienne. https://journals.openedition.org/anatoliaantiqua/1820

- Palazzo, E. (1990). L’évangéliaire d’Henri II et l’Apocalypse de Bamberg. Bulletin Monumental, 148(3), 324–325. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01340724

- Parpola, S. (n.d.). From whence the beast? The BAS Library. https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/sidebar/from-whence-the-beast/

- Pritchard, J. B. (1969). Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed., with supplement; W.F. Albright et al., Translators & Annotators). Princeton University Press.

- Rendsburg, G. A. (1984). UT 68 and the Tell Asmar seal. Orientalia, 53(4), 448–452. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43075752

- Rowland, C. (2005). Imagining the Apocalypse. New Testament Studies, 51(3), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688505000159

- Sazonov, V., Espak, P., Johandi, A., & Mõttus, S. (2021). Papers of the Formative Tendencies in Near Eastern Religions and Ideologies Conference, April 2019, Beirut. Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica, 27(2).

- Tsumura, D. T. (2011, November 8). The “chaoskampf” motif in Ugaritic and Hebrew literatures. In J.-M. Michaud (Ed.), Le Royaume d’Ougarit de la Crète à l’Euphrate: Nouveaux axes de recherche (Proche-Orient et littérature ougaritique II) (pp. 473–499). Sherbrooke: GGC. https://www.academia.edu/1076327

- Tsumura, D. T. (2020). The Chaoskampf myth in the biblical tradition. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 140(4), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.4.0963

- Uehlinger, C. (2024, March). Mastering the seven-headed serpent: A stamp seal from Hazor provides a missing link between cuneiform and biblical mythology. Journal Articles & Databases – Library and Information Science – Library Guides at UChicago. https://www-journals-uchicago-edu.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1086/727582

- Walther, I. F., & Wolf, N. (2005). Codices Illustres: The world’s most famous illuminated manuscripts, 400 to 1600. Taschen.

- Wangerin, L. E. (2019). Kingship and justice in the Ottonian Empire. University of Michigan Press.

- Yasenovskaya, A., Shelestin, V., & Nemirovsky, A. (2021, December 1). The iconographical and mythological contexts of serpent(s)-fighting scene on the Old Assyrian seal impression from Kültepe. Studia Antiqua Archaeologica. http://saa.uaic.ro/