Biblia Torres-Amat

Biblia Torres-Amat

By Sharon Hassive Guerra Álvarez

Project Synopsis

This work aims to illustrate and teach the reader about the historical and literary generalities surrounding the publication of the Torres-Amat Bible (1823), a Bible in Spanish translated taking into account editions in Greek and Hebrew. In the same way, we will talk about the gospel of Saint John which is part of the New Testament, and in a more precise and concrete way we will discussed and analyzed the story of the adulterous woman that appears in it, the one saved by Jesus Christ from being stoned to dead.

| Categories | Bible |

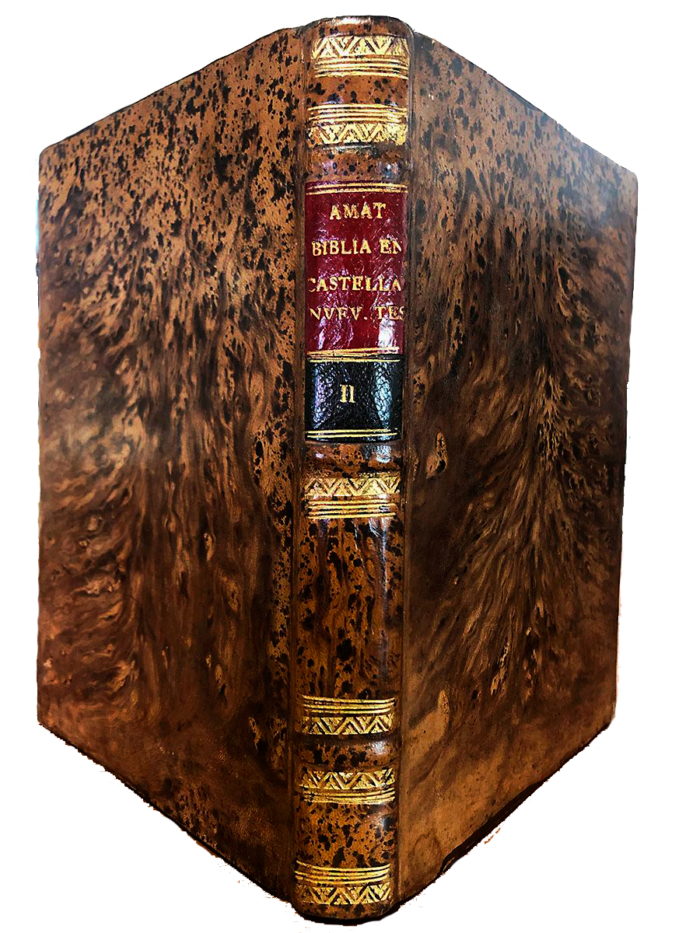

| Title | Biblia Torres Amat (also known as Biblia Petisco-Torres Amat) |

|---|---|

| Date | 1823 |

| Place | Barcelona, Spain |

| Contributor(s) | Translator: José Miguel Petisco Author: Félix Torres Amat Illustrator: Gustave Doré Publishing House: Montaner y Simón Editores (Barcelona), Don León Amarita (Madrid) |

| Language(s) | Spanish |

| Source | Available on Archive.org: Link to catalogue |

| Format | 29×21 cm |

Introduction to the Bible

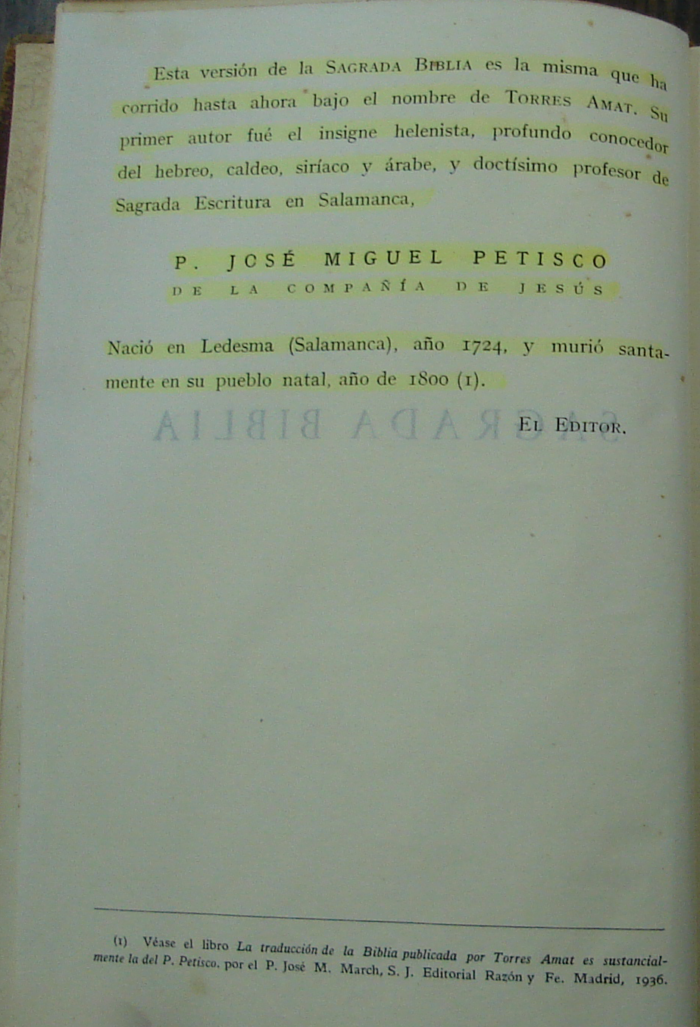

The Torres-Amat Bible is a bible whose elaboration was entrusted by the kings Charles IV of Spain (1748-1819) and Ferdinand VII of Spain (1784-1833) to the Spanish Catholic priest Félix Torres Amat (1772-1847) and translated from the Latin Vulgate by the priest José Miguel Petisco, (1724-1800) who was a professor of classical languages and Hebrew in France, Italy and Spain. It is one of the most important Catholic translations since 1433 with footnotes explaining the variants with respect to the Hebrew and Greek texts.

This translation is from the Latin Vulgate1, but has being made by comparing with the original Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek, work done mostly by José Miguel Petisco for more than 10 years until his death in 1800. In the notes of this Bible the word Jehovah is used when referring to the name of God in the Old Testament. The priest Torres Amat was in charge of its publication in 1823, followed in 1832 by a second edition because although it had the approval of the king and the favorable opinion of many bishops, the Sacred Congregation of the Index or Sacra Congregatio Indicis, that is, the ecclesiastical censorship, expressed certain reticence and suggested corrections that were immediately carried out by Torres Amat.

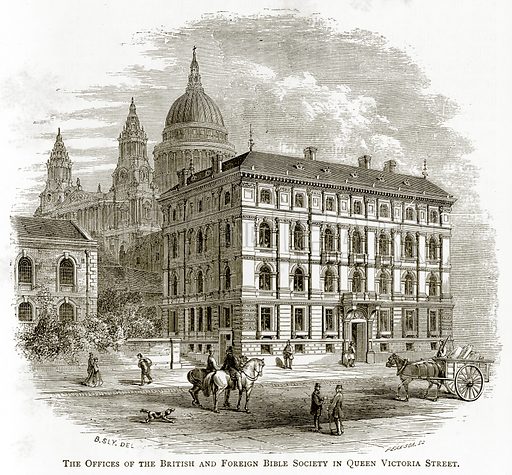

This edition of the bible was partially financed by the British and Foreign Bible Society or the Bible Society, and by the popular subscription opened by the Anglican pastor Andrew Cheaps among his English parishioners since it was superior to that of Father Scío although not more manageable for a simple reader, and that’s why they took the footnotes away.

History

Background and about the Sacred Congregation of the Index

The publication of the Torres-Amat Bible was strongly conditioned by the intervention of the Sacred Congregation of the Index, an official institution of the Catholic Church in charge of reviewing and censoring printed works from the 16th to the 20th century. Its central task consisted of the periodic and updated dissemination of the dreaded Index of Prohibited Books, which represented a substantial challenge in that historical context.

The authors deemed most perilous by the Index were categorized within the ‘first class’ of prohibited authors, signifying the utmost level of danger. A prevalent cause for inclusion in the Roman Index was the deviation of an author’s perspectives from the established doctrine of the Catholic Church. Additionally, authors or works were often labeled as politically subversive or morally controversial, contributing to their placement on the Index.

At a crucial moment, the Congregation of the Index requested that the second edition of the Torres Amat Bible incorporate more explanatory annotations of the Holy Scriptures, in order to prevent this work from being included in the Index of Prohibited Books. In those days, Bible translation was a delicate matter, even considered heresy if not carried out under the strict guidelines of the Catholic Church.

This episode became especially sensitive in 1824 when “Observaciones pacíficas sobre la potestad eclesiástica” by Torres Amat’s uncle, Félix Amat de Palau y Pons (1750-1824), bishop of Palmira, was added to the Index of Prohibited Books. Since Torres Amat had defended this work, the Catholic Church viewed his position with distrust. Despite this, Torres Amat chose to abide by all the orders of the Congregation, incorporating the requested annotations in the second edition of the Torres Amat Bible. This act of submission to ecclesiastical guidelines underlines the delicacy and complexity of the relationships between the Church and the scholars involved in the translation of sacred texts during that historical period.

Controversy with Translations

As previously highlighted, the majority of the translation work comes from Jesuit priest José Miguel Petisco, a prominent member of the Catholic pioneers dedicated to biblical translation into Spanish. Initially, his valuable work did not receive the recognition it deserved, and many years passed before justice was done to his contribution as a translator in the new editions of the Torres Amat Bible. This case is considered by many academics to be one of the most significant plagiarisms in all of Spanish literature, not only due to the total omission of any mention or thanks to Petisco, but also because it has not been verified that Félix Torres Amat has made any contribution to the Bible.

In the events of this story, the outstanding figure of the Spanish clergyman, historian and writer Joaquín Lorenzo Villanueva y Astengo (1757-1837) emerges. This notable individual, a close friend of Torres Amat plays a significant role in promoting the dissemination of Felix’s Bible among the Spanish exiles in the English capital. It is suspected that Lorenzo Villanueva could have contributed to the cover-up of the alleged intellectual theft related to this biblical translation.

The clergyman, a frequent praiser of Torres Amat’s erudition and solid scientific knowledge, is involved in uncertainty about his degree of participation in the concealment of this plagiarism. Speculation suggests that, if it had occurred, could have been largely related to the conflict between the religious orders of the Jesuits, to which José Miguel Petisco belonged, and the order of the Jansenism, to which Félix Torres Amat was linked as well as Villanueva. This is important to take into consideration because of the conflict between the Jansenism and the Jesuits. The Jesuits were noted for their more flexible and adaptive approach to theological and moral issues, but this caused friction with the Jansenism, who viewed Jesuit teachings as lax and too permissive compared to their stricter interpretation of the faith.

The Bible

Warnings

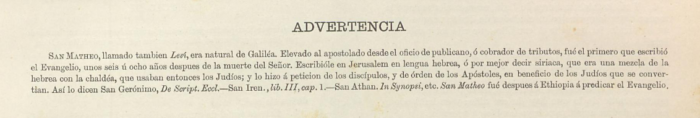

At the beginning of each of the four gospels, Torres Amat presents warnings that serve as introductions to the respective evangelists. These sections provide context and commentary on the content of each gospel, addressing topics such as authorship, purpose, historical context, and distinctive characteristics. The Bishop of Astorga sought to enrich readers’ understanding, offering these warnings as useful guides before they immerse themselves in the sacred texts. It is important to note that these introductions reflect the interpretations and explanations of Torres Amat, evidencing his theological and pastoral perspective.

TRANSLATION

WARNING

SAINT MATTHEW, also called Leví, was born in Galilee. Elevated to the apostolate from the position of a tax collector, he was the first to write the Gospel, about six or eight years after the death of the Lord. He wrote it in Jerusalem in the Hebrew language, or more precisely Syriac, which was a mixture of Hebrew and Chaldean used by the Jews at that time. He did so at the request of the disciples and by order of the Apostles, for the benefit of the Jews who were converting. This is stated by Saint Jerome in De Script. Eccl., Saint Irenaeus in lib. III, cap. 1, and Saint Athanasius in Synopsi, etc. Later, Matthew went to Ethiopia to preach the Gospel.

TRANSLATION

WARNING

SAINT MARK wrote his Gospel in Rome, at the request of the faithful, according to what he had heard from St. Peter, who approved it and proposed it with his authority to the Church to read it, as St. Geronimo says (Catal. de Script. Eccl.) It is believed that St. Mark was a disciple of St. Peter, and that he is the one he calls his son at the end of his first letter. St. Augustine calls him a compendium of St. Mathew; for in fact he refers to almost the same things, although more briefly: however, he is more extended in certain passages; and sometimes he adds in a few words very important things. The Expositors do not agree whether he wrote in Greek or Latin. It is believed that he wrote it about the year 45 of Jesus Christ, 12 after the passion and death of the Lord.

TRANSLATION

WARNING

SAINT LUKE, was a physician born in Antioch, as Saint Paul tells us. He was a disciple of this Apostle, whom he accompanied on his travels. He is thus called by his esteemed friend, who says that he is the glory of Jesus Christ and is praised throughout the Church for his Gospel. He wrote this Gospel in Greek, around the year 26 after the death of Jesus Christ, according to Saint Jerome and other authors cited by Baronius. Luke added, especially concerning the birth of Saint John the Baptist and the infancy of Jesus Christ, to what Matthew and Mark had already said. He suffered martyrdom in Patras, a city in Achaia, at the age of 84, according to Nicephorus, and in the 29th year after the death of Jesus Christ, according to Saint Gregory Nazianzen. Niceph., lib. II cap. XLIII. – S. Greg. Naz., Orat. I, in Julian.

TRANSLATION

WARNING

SAINT JOHN, born in Bethsaida in Galilee, near the Sea of Tiberias, the son of Zebedee and Salome, and the brother of James the Greater, with whom he was called to the apostolate while both were with their father mending nets in the boat. Later, being the bishop of Ephesus, he was taken to Rome during the persecution of the Emperor Domitian around the year 95 of Jesus Christ. He was thrown into a boiling cauldron of oil but emerged more refreshed and vigorous. Exiled by the same emperor to the island of Patmos, he wrote the Apocalypse there. After the death of Domitian, Saint John returned to Ephesus, where, at the request of the bishops of Asia, he wrote his Gospel against Cerinthus and other heretics, especially to refute the error that the Ebionites were beginning to spread by denying the Divinity of Jesus Christ. (Tert. Praescript,. cap. XXXVI. – S. Hier. cont. Jov. lib. I, cap. XIV: et De Script. Eccl. – S. Iren., lib. III, cap. I) He wrote it in Greek around the year 96 of Jesus Christ, supplementing many things that the other three Evangelists omitted, as noted by Saint Augustine. He remained a virgin throughout his life and died very old in the year 68 after the death of the Lord, or in the year 102 of Jesus Christ and 35 years after the fall of Jerusalem, as affirmed by Saint Jerome.

About the Footnotes

As for footnotes, footnotes in the Torres-Amat Bible generally contain explanations, comments or clarifications by the translator on certain biblical passages. These footnotes may include theological, historical or linguistic information to help readers better understand the context or meaning of the verses. It should be noted that footnotes may vary between different editions of the Torres Amat Bible, as some publishers add their own clarifications or comments.

The footnotes are arguably the greatest contribution that Félix Torres Amat made to the Petisco bible and a large part of these contributions come from the clarifications that the church asked Torres Amat to make for its second edition and to avoid being included in the Index of Prohibited Books.

Mary Magdalene and the Adulterous Woman.

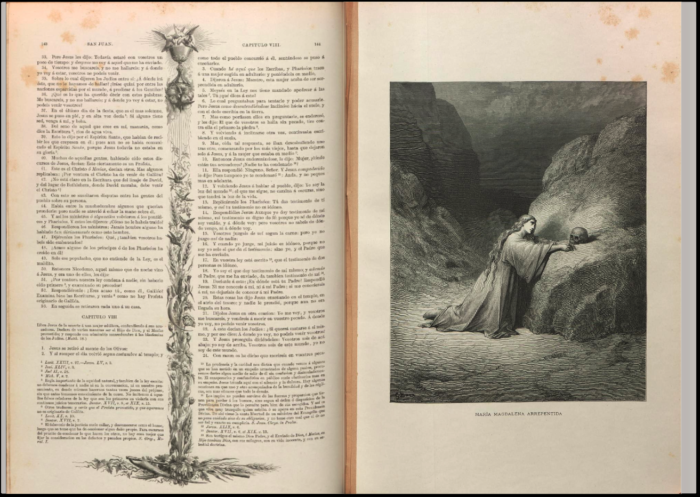

The biblical story to be addressed is that of the adulterous woman accused by the people and saved by the Lord Jesus Christ. This story is specifically found in the Gospel of John 8:1-11 and is portrayed in the Torres Amat Bible in Chapter VIII. Jesus withdraws to the Mount of Olives, and upon returning to the temple, the people surround him. Sitting down, Jesus begins to teach them. It is at this moment that the Scribes and Pharisees bring a woman accused of adultery to Jesus and say to him, “Teacher, this woman was caught in adultery. Now Moses, in the Law, commanded us to stone such women. What do you say?” They did this to test him and accuse him, but instead, he wrote on the ground with his finger. Then he stood up and said, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” He continued writing on the ground while the men who had accused her began to withdraw, the elders first, leaving him alone with the woman. Jesus said to her, “Woman, where are your accusers? Did they not condemn you?” She replied that they did not, and Jesus told her that he would not condemn her either and instructed her to go on her way without sinning anymore.

What is noteworthy is that at no point is the woman given a name in the narrative. However, she is commonly associated with Mary Magdalene. In the Torres Amat Bible with illustrations by Gustave Doré2 (1832-1883), the title of the image corresponding to the adulterous woman professes Repentant Mary Magdalene.

There is some confusion regarding the figure of Mary Magdalene and the adulterous woman due to various factors, one of which is precisely the interpretation by artists, merging her with the image of the adulterous woman. Creative liberties in writings, sermons, and paintings could be responsible for this confusion persisting in our minds.

However, it is essential to clarify that occasions where Mary Magdalene is mentioned include when she is healed by Jesus, who casts out the seven demons that invaded her body, and later accompanies him alongside other women on a pilgrimage (Luke 8:2-3), she is also a witness to the crucifixion, being one of the women standing by the cross (Matthew 27:56, Mark 15:40, John 19:25), observes Jesus’ lifeless body and how they prepared the ointments for his burial (Luke 23:55-56, Mark 15:47). Additionally, Mary Magdalene is the first to discover the empty tomb (Matthew 28:1-10, Mark 16:1-8, Luke 24:1-12, John 20:1-18) and she is among the first witnesses to the resurrection of Jesus.

- It is a translation of the Bible into Latin, made at the end of the 4th century (from 382 AD) by Jerome of Strydon (Saint Jerome). Before the Vulgate was used, the Vetus Latina was usually used. ↩︎

- French artist, painter, sculptor and illustrator ↩︎

Bibliography

Astorgano Abajo, Antonio. “José Miguel Petisco.” Real Academia de la Historia. 2007. https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/20810/jose-miguel-petisco.

Cárcel Ortí, Vicente. “Félix Torres Amat.” Real Academia de la Historia. 2018. https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/9055/felix-torres-amat

Internet Archive. “La Sagrada Biblia T. 4.” Digitized in 2018. https://archive.org/details/AI159/mode/2up

March, José María. La traducción de la Biblia publicada por Torres Amat es sustancialmente la del P. Petisco: estudio y publicación de numerosos documentos inéditos importantes para la Historia de España. Madrid: Razón y Fe, 1936.

Mas i Usó, Pascual. “Polémica (1794) entre Villanueva y el ex novicio jesuita Miguel Elizalde de Urdioz (Guillermo Díaz Luzeredi).” Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/joaqun-lorenzo-villanueva-y-los-jesuitas-0/html/01d17178-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_19.html.

Moreno, Doris, and Pedro Rueda Ramírez. “Propaganda protestante e imprentas en Barcelona. El colportor James Graydon y los impresos de Antonio Bergnes de las Casas (1835-1840).” Información, cultura y sociedad: revista del Instituto de Investigaciones Bibliotecológicas. University of Buenos Aires, 2021. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/2630/263066699005/html/

Pereda, J. 1915. El P. José Petisco, S.J.: su tiempo y sus obras. Madrid. 30 pp.

Svoljšak, Sonja. “Book Censorship and Banned Books.” Europeana, 2018. https://www.europeana.eu/es/blog/book-censorship-and-banned-books-the-index-librorum-prohibitorum.

Serrano, Rafael A. 2017. Historia de la Biblia en español. Una introducción. 2.ª edición. Fort Worth: Autor.

“The Sacred Congregation of the Inquisition Begins Publication of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.” History of Information. https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=31.

Torres Amat, Fèlix. 1838. Sobre las versiones de la Biblia sin notas. Reflexiones que hice presentes al supremo gobierno y que añadidas algunas palabras se extractaron después de la Gaceta del 5 de este mes y en otros periódicos. Madrid: Imprenta que fue de Fuentenebro, a cargo de Alejandro Gomez.

https://books.google.fr/books?id=4NwZKfRsbTIC&pg=PA8&lpg=PA8&dq=Sobre+las+versiones+de+la+Biblia+sin+notas.+Reflexiones+que+hice+presentes+al+supremo+gobierno+y+que+a%C3%B1adidas+algunas+palabras+se+extractaron+despu%C3%A9s+de+la+Gaceta+del+5+de+este+mes+y+en+otros+peri%C3%B3dicos.&source=bl&ots=ol2zfzdqOI&sig=ACfU3U1S5C92-Fo-YJ5KUvFzO_pszxj67w&hl=es&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi5-K_t4OyCAxUsRaQEHeB_K94Q6AF6BAgJEAM#v=onepage&q=Sobre%20las%20versiones%20de%20la%20Biblia%20sin%20notas.%20Reflexiones%20que%20hice%20presentes%20al%20supremo%20gobierno%20y%20que%20a%C3%B1adidas%20algunas%20palabras%20se%20extractaron%20despu%C3%A9s%20de%20la%20Gaceta%20del%205%20de%20este%20mes%20y%20en%20otros%20peri%C3%B3dicos.&f=false

“Vida del Ilmo. Señor Don Felix Amat.” Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/vida-del-ilmo-senor-don-felix-amat-arzobispo-de-palmyra/html/ff37b332-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_3.html. 2001.

Zamora Vicente, Alonso. “Félix Torres Amat.” Real Academia Española (RAE). 1999. https://www.rae.es/academico/felix-torres-amat