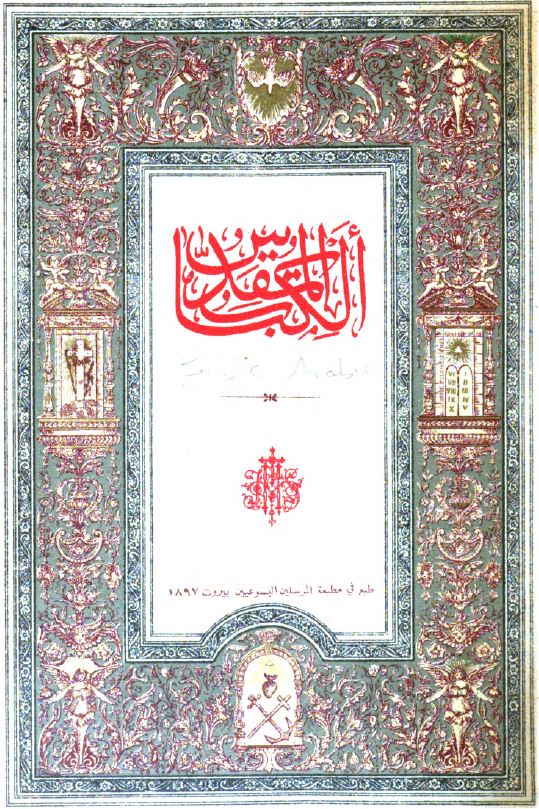

Van Dyck & Smith Arabic translation of the Bible

Van Dyck & Smith Arabic translation of the Bible

by Ali Abu Rmeileh

- Author: Van Alen Van Dyck, Eli Smith

- Title: الكتاب المقدس “AlKitab AlMuqaddas” (The Holly Book)

- Date: 1897

- Edition: Unknown

- Pages: 562 Pages

- Language: Arabic

- Source:

archive.org

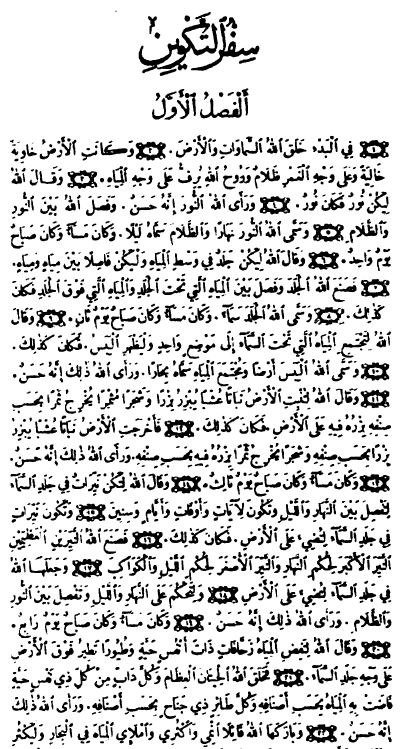

The Van Dyck and Smith Arabic translation project of the Bible started in Beirut, Lebanon in 1847 and was funded by the Syrian Mission and the American Bible Society. The first man behind the project was Drs Eli Smith, an American Protestant scholar, and missionary from Northford, Connecticut. He came to work as a missionary on the island of Malta after completing his studies, and from there in 1827 to Beirut to learn the Arabic language. And around 1837, he was entrusted with supervising the printing of the Arabic Bible, later Cornelius Van Alen Van Dyck was put in charge to complete the project after Eli Smith’s death in 1857, he studied Arabic in Beirut under skillful authors like Butrus al-Bustani, Nasif al-Yaziji, and Yusuf al-Asir. The New Testament was completed in 1860, followed by the Old Testament in 1865. More than 9 million copies of this translation have been distributed since 1865. the version has been accepted by the Syriac Church, the Coptic Church, and the Protestant churches. The translation was based mostly on the same Textus Receptus sources as the English King James Version and follows a more literal style of translation. The original manuscript copies are preserved in the Near East School of Theology (NEST) in Beirut.

The old master translation was done at the start of the revival of contemporary Standard Arabic as a literary language, and consequently many of the terms coined failed to enter into common use. One indication of this is often a recent edition of the Van Dyck printed by the Bible Society in Egypt, which has a glossary of little-understood vocabulary, with around 3000 entries. additionally, to obsolete or archaic terms, this translation uses religious terminology that Muslim or other non-Christian readers might not understand like ișḥāḥ, a Syriac borrowing meaning a chapter of the Bible or tajdīf, the word for blasphemy.) It should even be noted that an Arab Muslim reading the Bible in Arabic (especially if reading the New Testament) will find the fashion quite different from the fashion that’s utilized in the Qur’an (this is more or less true of all Arabic translations of the Bible). Also of note is that the proven fact that religious terminology familiar to Muslims wasn’t considerably employed in this version of the Bible, as is that the case in most Arabic versions of the Bible.

The distribution of Scripture and tracts was the principal activity of American Protestant missionaries in Palestine when the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) arrived in the 1820s. The majority of their audience consisted of Christian visitors visiting Jerusalem for Christmas and Easter. The use of Arabic literature was first quite limited. On the one hand, reaching out to Muslims could result in the death penalty under Ottoman law; on the other side, Protestant connections with Arab Christian groups were shaky, if not hostile. True altered with time, and the missions were ready to build schools, clinics, and churches across Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon. The need for an Arabic Bible translation was identified as a top priority in this setting.

However, before taking action, a few questions needed to be answered. For starters, such a translation would be expensive and time-consuming, so why should the mission spend time and money on it? Second, were there any suitable Arabic Bible translations already available? If that was the case, why would the American Mission seek a translation done by its own people? Third, how would the quality of a fresh translation be guaranteed if one was required?

However, the team was confronted with a more serious problem: widespread illiteracy. It would be pointless to put the Bible in the hands of individuals who couldn’t read or write. Few books were written or published in Arabic throughout the 18th century due to the low level of literacy among the general people, particularly in the countryside and among desert tribes. Classical Arabic had receded in relation to Turkish, and the gap between written Arabic (i.e. classical) and spoken Arabic had expanded to the point where the latter had practically become its own language. As a result, the endeavor of translating the Bible into Arabic would only be worthwhile if the mission schools’ work of teaching Arabs to read and write progressed. As a result, both Dr. Smith and Dr. Van Dyck were active in the establishment of schools and teaching in them.

Many people believe that the Arabic Bible translation by the American mission in the 19th century was the first Arabic translation of the entire Bible, especially because this is the most popular and oldest version in use. However, this is not the case. There were many Arabic translations of the Bible from the 9th century until the 19th century, according to an account given by Dr. Van Dyck himself. At least one of these complete Bible translations, the ‘Propaganda,’ was familiar to the missionaries and was used by them. (The majority of the other translations only comprised portions of the Bible.)

Furthermore, the Propaganda edition was produced in three enormous volumes, making it impossible to transport, and it was extremely expensive, with only monasteries, churches, and affluent individuals able to afford it. We can deduce from this that the vast majority of people were unaware of the contents of the Bible and had never personally handled one. Another reason for a fresh Arabic translation of the Bible was this.

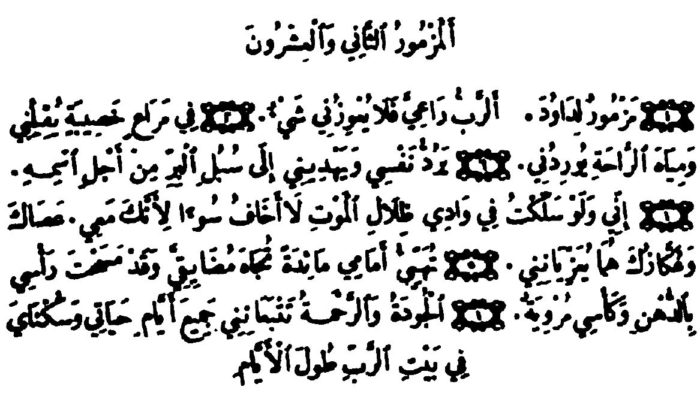

*******************************مزمور لداود. الرب راعي فلا يعوزني شيء*****************************

****************************في مراع خضر يربضني . إلى مياه الراحة يوردني******************************

*******************************يرد نفسي. يهديني إلى سبل البر من أجل اسمه****************************

****************اني ولو سلكت في وادي ظلال الموت لا أخاف سوءاً لأنك معي. عصاك وعكازك هما يعزيانني*****************

*********************تهي أمامي مائدة تجاه مضايقي وقد مسحت رأسي بالدهن وكأسي مروية*******************

******************** الجود والرحمة تتبعانني جميع أيام حياتي وسكناي في بيت الرب طول الأيام******************

Bibliography:

- Isaac H. Hall, ‘The Arabic Bible of Drs. Eli Smith and Cornelius V. A. Van Dyck’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 11 (1885), 276–86 (pp. 283–284).

- Ghassan Khalaf, ‘The role of evangelicals in translating the Bible into Arabic’ (Beirut, Lebanon, 1998), pp. 1–8 (p. 5).

- Margaret R. Leavy, ‘Eli Smith and the Arabic Bible’, Yale Divinity School Library: Occasional Publication, 1993, 1–25 (p. 7).

- Ajaj, Azar. “The Van Dyck Bible Translation.” Nazareth Evangelical College, October 4, 2014. https://www.nazcol.org/blog/294/the-van-dyck-bible-translation-by-azar-ajaj/#_ftnref5.