The London Polyglot Bible

The London Polyglot Bible – Biblia sacra polyglotta / edidit Brianus Waltonus

by Razan Zein El-Abidine

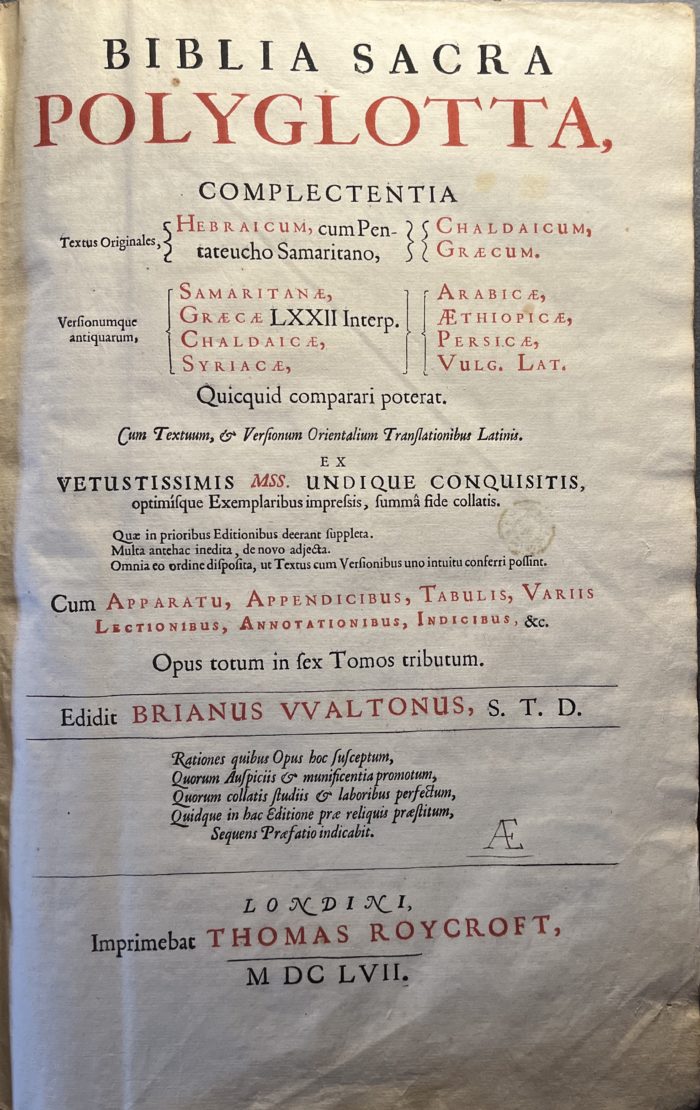

The London Polyglot Bible is a masterpiece created in the early modern period by Brian Walton, bishop of Chester during 1660. This outstanding edition is the result of a collaboration between Walton and four other men known to be pioneers of the art of bookmaking during that era. This polyglot bible was printed in London between 1655 and 1657 at the printing press of Thomas Roycroft, who was appointed printer of King Charles II for oriental languages as a reward. This bible includes engravings by Pierre Lombart, John Webb, and Václav Hollar. The Bible this article is based on was found in the collection of Bibliothèque Grammont at Centre Diocésain in Besançon. It can also be found in France at the libraries of the following institutions: Université catholique de Lyon, Institut catholique de Paris, Institut Catholique (Toulouse).

| Title | Biblia sacra polyglotta, complectentia textus originales, Hebraicum, cum Pentateucho Samaritano, Chaldaicum, Graecum. Versionumque antiquarum, Samaritanae, Graecae LXXII interp. Chaldaicae, Syriacae, Arabicae, Aethiopicae, Persicae, vulg. Lat. Quicquid comparari poterat. Cum textuum, & versionum Orientalium translationibus Latinis … Cum apparatu, appendicibus, tabulis, variis lectionibus, annotationibus, indicibus, & c. Opus totum in sex tomos tributum. |

| Contributors | Walton, Brian (1600?-1661). (Editor) Lombart, Pierre (1612?-1681?). (Engraver) Webb, John (1611-1672). (Engraver) Hollar, Václav (1607-1677). (Engraver) |

| Place | London, United Kingdom |

| Date | 1654-1657 |

| Printer | Roycroft, Thomas (16..-1677) |

| Format | in-folio |

| Extent | 6 volumes |

| Languages | Polyglot (Hebrew, Latin, Samaritan, Chaldean, Greek, Syriac, Ethiopian, Persian and Arabic) |

The best for the last – The London Polyglot among its contemporaries

The period between the second half of the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century was indeed known as the era of the greatest polyglot bibles history has known. The first polyglot Bible that appeared during this period was Complutensian (1514-1517) printed in Alcalá de Henares, a city in the center of Spain. Later during the same century, Antwerp Polyglot (1569-1572) or Biblia Regina (King’s Bibles), was printed in Antwerp , Belgium. It was made at the printing press of Christopher Plantin and supervised by Spanish Orientalist, Benito Arias Montano. The Antwerp Polyglot had text in five languages: Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Aramaic and Syriac. Following that was the Paris Bible (1628-1645). This polyglot bible contains seven languages: Hebrew, Samaritan, Chaldean, Greek, Syriac, Latin and Arabic. Finally, between 1654 and 1657 the London Polyglot Bible was printed. It was the most comprehensive since it contained more languages than the polyglots that preceded it.

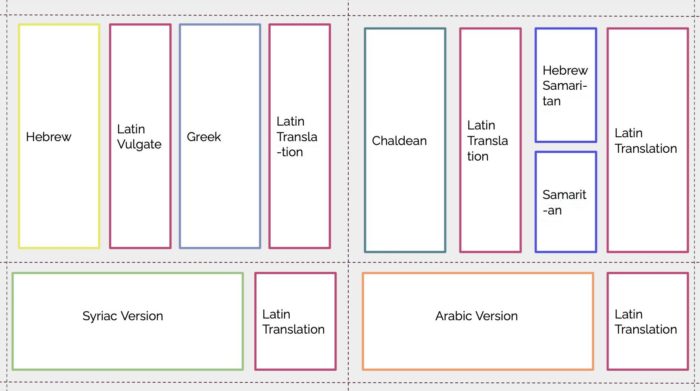

The London Polyglot contained up to nine languages namely: Hebrew, Latin, Samaritan, Chaldean, Greek, Syriac, Ethiopian, Persian and Arabic. The Hebrew version is accompanied by an interlinear Latin version of Arias Montano. Yet, it is important to point out that he full text doesn’t exist in all nine languages, for example in edition found at Bibliothèque Grammont in Besançon, the first volume that contains the Genesis has the text in the following languages: Hebrew, Latin, Greek, Syriac, Chaldean, Hebrew Samaritan, Samaritan and Arabic. It is true what Millers says about this polyglot: “The fruits of a century-and-a-half’s study of the Bible and a half-century’s closer contacts with the Ottoman Empire were displayed in the nine languages arrayed across the page …”. Below is an image representing the layout of texts of a double page view of the bible. If we take a look at, we will instantly realize that in fact Latin was the lingua franca dominating this Bible. It was the reference of all languages, since all versions had a parallel Latin translation.

Genesis 11:1-5 – An interactive display

The figure below displays extracts cut out of pages 40-41 of the London Polyglot Bible. Placing the photos in interactive visualizer Juxtapose developed by knight lab. This enables us to look closely at the multiple scripts used to print the volumes of this polyglot bible. Indeed, it is a moment to delve into critical scholarship while appreciating the expert craftsmanship devoted to making this edition happen.

What we see below is Genesis 11:1-5 in Hebrew with interlinear latin translation, Latin Vulgate, Greek and Arabic. We can also see the parallel Latin translation that accompanied the Arabic version. This sample of the Bible is to demonstrate how this polyglot can facilitate comparison between versions.

A result of impeccable craftsmanship – technical aspects of printing

The London Polyglot Bible is considered by both biblical scholars and historians of the art of book making as probably the greatest accomplishment of 17th century England. (Knop, 1977)

The Bible ecompasses six large volumes that required time, energy and expertise to be done. What is most remarkable is the type used to print this volume. As we can see in figure 1, the text is split into columns and setting the type while avoiding mistakes and mixing up the different scripts was quite a challenge. This was considered a huge triumph on technology and the London Polyglot was the first to display the versions side by side in this form.

Also, before even starting the printing process, the creation in the type to be used for the oriental languages versions was not an easy task. Orientalist printers such as Roycroft had to use the experience of experts from the East, specially Ottoman Empire to teach them the making of the type and basic language and spelling principales.

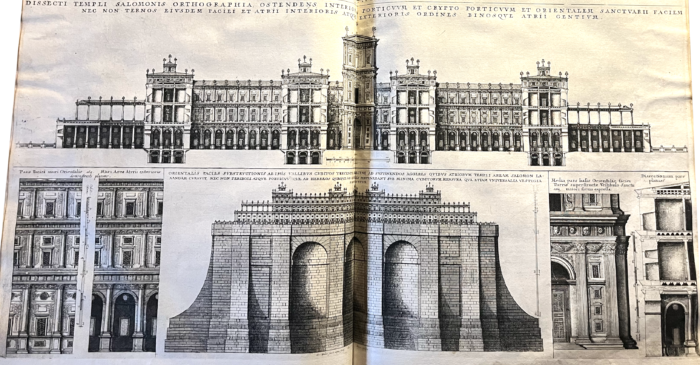

An aspect we should not leave out when discussing the printing process is the engravings present in the Bible. Which were required to be printed alone after all the text was set. The first volume of the polyglot was enriched with maps, and several illustrations and plans of historic monuments such as the one in figure 2.

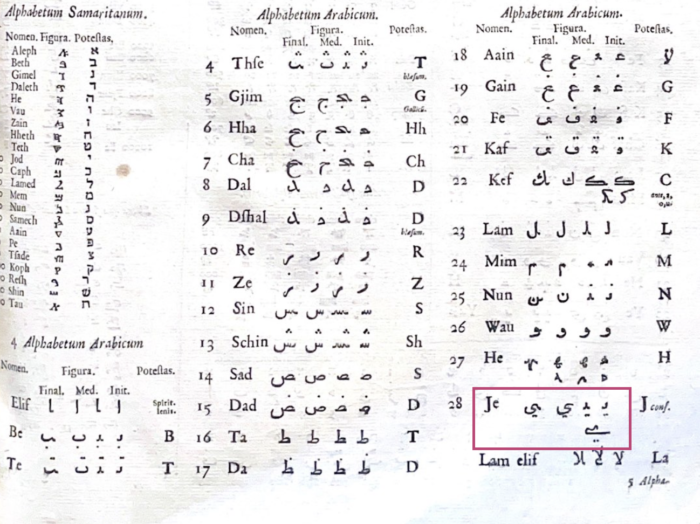

The table in figure 3 is very important because it shows the type used to print the Arabic list whether the letter was detached in its initial, medial or final position in a word. If we look at the letter 28, we will see that it is missing al-alif al-maqsūrah = ى. This perfectly explains why every word that contains this letter in the text ended with a yā’ = ي in its final position in the word. And in fact it is not a spelling mistake. It is not part of the type they used.

Walton’s objective and the reception of the Bible

It is no secret that the political history of England during the 17th century was a period of conflict and rebellion. During this century, a civil war ignited, King Charles I was executed after the people rebelled against him. They have lost faith in their king and state. Nonetheless, his son Charles II’s reign began soon after his father’s death when the soldier George Monck took over the army and accepted Charles’ letters asking for the restoration of his crown. Monck also called for open parliamentary elections.

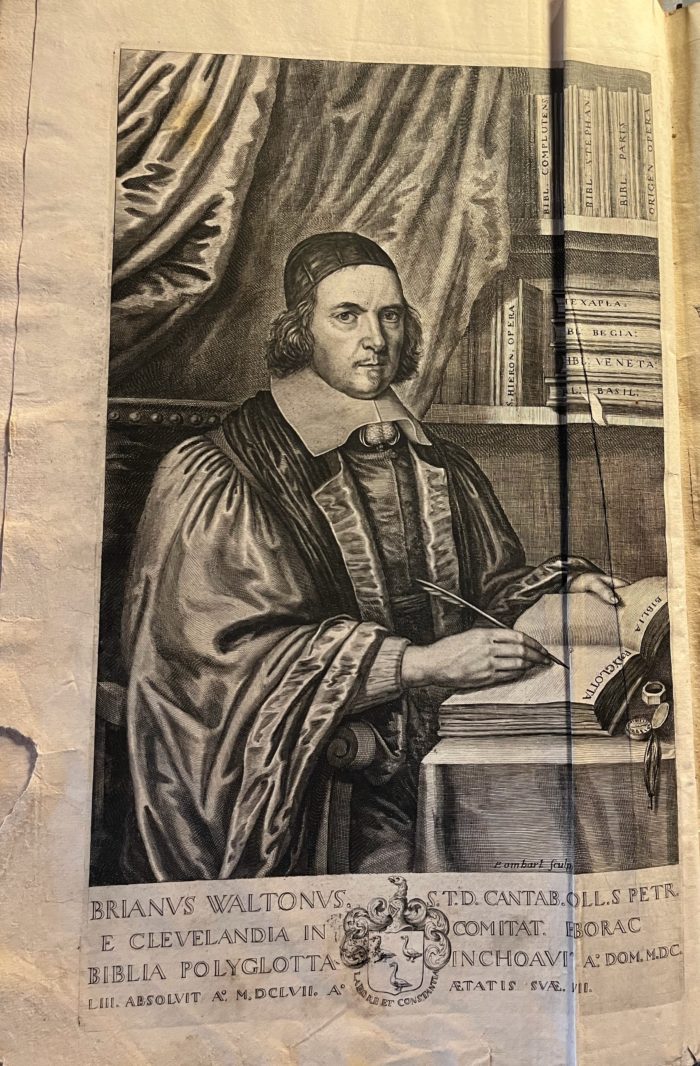

To the left we see the frontispiece of the polyglot engraved by Pierre Lombard, it shows a portrait of Brian Walton in his study editing the polyglot Bible with all the different bible translations and versions on the shelves behind him. Walton’s intention was never text comparison, he blamed variations on scribes and mistakes in older manuscript versions. His goal was to establish an edition that included the Bible in its original languages because he believed that the most ancient versions would bring peace among the people and restore their faith.

Walton’s project was never supported by the state as Cromwell’s council never supported him financially. Instead, Walton sought the help of the English people. Starting 1652, he started offering subscriptions to the people for the polyglot bible priced at ten pounds. Soon, the required financial needs were attained and the printing of the bible started as scheduled during 1654.

Walton’s polyglot was heavily supported by the English society even before the printing was complete. When it was finally released, it acquired a great reception from the people as it had a strong scholarly impact. What added to its scholarly value compared to its predecessors, is the introductory material it contained. The text was rich with tables with the letters of all the scripts used, with full explanations on how they are employed. It also included critical essays, appendices, variant readings, annotations, and indexes. This material made the Bible an indispensable source for scholarly work which was used up until the 19th century. Even in the 20th century we still observed many scholarly publication about this bible. One of them is the dissertation of Judy A. Knop in 1977: The editing and publishing of the “London Polyglot” (Bible). Knop’s study focused on the the state of biblical studies and art of printing at the time the Bible was printed.

A transcription of the Arabic translation of Genesis 11:1:10 enriched by a romanized version

- The Arabic transcription below was done with no intervention from my part. The text was copied as it was printed in the edition.

- The romanization was done in accordance with the text transcribed with no corrections nor interventions on my part.

| Latin Vulgate | Arabic Romanization | Arabic transcription | |

| 1 | Erat autem terra labii unius & sermonum eorundem | Wa-kāna jamī‘u ahla al-arḍi ahla lughahtin wāḥidatin wa-kān al-kalāmu wāḥidan | وكان جميع أهل الأرض أهل لغة واحدة وكان الكلام واحدًا |

| 2 | cumque proficiscerentur de oriente invenerunt campum in terra Sennaar & habitaverunt in eo | Wa-kāna lamma raḥalū mina al-mashriq wajadū buqa‘an fī balad al-Shīnūr fa’aqāmū thumma | وكان لما رحلوا من المشرق وجدوا بقعًا في بلد الشّينور فأقاموا ثمّ |

| 3 | dixitque alter ad proximum suum; Venite, faciamus lateres, & coquamus eos igni. Habueruntque lateres pro saxis; & bitumen pro cemento: | Wa-qālū ba‘ḍahum li-ba‘ḍin ta‘lū nulabbinu lubnan wa-nunḍijuhu ṭakhan, fakān lahum al-lubnu kal-ḥijari wa-al-qufuru makān al-ṭīni | وقالوا بعضهم لبعضٍ تعالوا نُلَبِّنُ لبنًا وننضجهُ طخًا، فكان لهم اللُبْنُ كالحجارِ والقُفُرُ مكانَ الطينِ |

| 4 | Et dixerunt; Venite, faciamus nobis civitatem et turrem cuius culmen pertingat ad caelum : et celebremus nomen nostrum antequam dividamur in universas terras. | Wa-qālū ta‘ālū linabī lanā qaryatan wa-majdalan ra’suhu yudāfī al-samā’. Wa- naṣna‘ lanā āsman kay lā yatabbadadu ‘alī wajhi al-ard. | وقالوا تعالوا لنبني لنا قريةً ومَجْدَلًا راءسه يدافي السماء. ونصنع لنا آسمًا كيلا يتبّدد علي وجه الأرض |

| 5 | descendit autem, Dominus ut videret civitatem et turrim, quam aedificabant filii Adam. | Fa-inḥadara malā’ikah li-naẓri al-qaryah wa-al-majdal alladhi banāhu banū Ādam | فانحدر ملائكة لنظرِ القرية والمجدل الذي بناهُ بنو ءآدم |

| 6 | Et dixit; Ecce, unus est populus, & unum labium omnibus: cœperuntque hoc facere, nec desistent a cogitationibus suis, donec eas opere conpleant. | Wa-qāla Allāhu huwadhā hum sha‘bun wāḥidun wa-lughatun wāḥidatun li-jami‘ihum, wa-hādha mā ikhtārū ann yaf‘aluh. Wa-al-ān lā yafuqhum jami‘ mā halammū bihi li-yaṣna‘ūh. | وقال الله هوذا هم شعبٌ واحدًٌ ولغةٌ واحدةٌ لجميعهم، وهذا ما إختاروا أن يفعلوهُ. والآن لا يفقهم جميع ما هلموا به ليصنعوهُ |

| 7 | Venite igitur descendamus, & confundamus ibi linguam eorum, ut non audiat unusquisque vocem proximi sui. | Lakinanī awridu amran ushattitu bihi lughātihum ḥattà lā yasma‘a kullu farīqin lughata ṣāḥibihi. | لكنني أوردُ امرًا أُشتِّتُ به لغاتِهم حتى لا يسمعَ كلُّ فريقٌ لغةَ صاحبهِ |

| 8 | Atque ita divisit eos Dominus ex illo loco in universas terras, & cessaverunt aedificare civitatem. | Wa-baddaduhumu Allāhu min thumma ‘alī wajhi al-arḍi, wa-āntahū ‘an binā al-qaryah. | وبددُهمُ اللهُ من ثم على وجهِ جميعِ الأرضِ، وآنتهوا عن بنآء القريةِ |

| 9 | Et idcircò vocatum est nomen eius, Babel, quia ibi confusum est labium universae terrae: & inde dispersit eos Dominus super faciem cunctarum regionum. | Wa-lidhalika usmiyat Bābil li’anna bihā balbala Allāhu lughata ahli al-arḍ. Wa-min thumma baddaduhum ‘alī jamī‘i wajhihā. | ولذلكَ اسميت بابل لأنَّ بها بلبل الله لُغَةَ اَهلِ آلارضِ. ومن ثمَّ بددُهمُ اللهُ علي جميعِ وجهِها |

| 10 | Hæ generationes Sem : Sem erat centum annorum quando genuit Arfaxad biennio post diluvium. | Hadhā sharḥu awlāda Sām: lamma kāna Sāmu ābin ma’yati sanatin awlad Arfakhshāda li-sanatayn ba‘da al-ṭawafān. | هذا شَرحُ أولاد سام : لمّا كانَ سامُ آبنَ مأيةِ سنةٍ أولدَ أرفخشادَ لسنتين بعد الطوفان |

Source of the Arabic version in the London Polyglot Bible

What we surely know is that Walton was an orientalist and heavily involved in studying versions of the Bible in oriental languages where he compiled published in 1655, Introductio ad lectionem linguarum orientalium, hebraicae, chaldaicae samaraitae, syriacae, arabicae, perisaea, armenae, coptea. A complication of notes and explanations about bibles in oriental languages, so we might suggest that the Arabic translation of the polyglot comes from several languages. We know that part of the Pslams published in the polyglot bible is the translation of ʻAbd Allāh ibn Faḍl al-Antākī. However, it is not clear in literature published so far where the Old testament, Genesis specifically came from.

A comparison to al-Kitāb al-Muqada

Below are examples of some of the variations we noticed between the London polyglot’s Arabic translation of Ibrahīm al-Yāzijī, Naṣif al-Yāzijī (Ibrahīm’s son) and Buṭrus al- Bustānī. The Bible translation of the Yāzijīs and Bustānī is known to be the first translation using the modern contemporary Arabic language. This bible is know by the name Van Dyke’s version of the Bible because at the time Cornelius Van Dyke, a Professor at the American University of Beirut, who was the leader of the American Protestant missionaries and approved this translation. Generally, all the variations were related to language use and grammar, none of which affected the meaning of the text.

Genesis 11:1

Wa-kāna jamī‘u ahla al-arḍi ahla lughahtin wāḥidatin wa-kān al-kalāmu wāḥidan

And the earth was of one tongue, and of the same speech.

The term that appeared in the polyglot bible for tongue was lughatun, which means language. However, in Bustānī and Yāzijīs’ translation we see the word lisanun, which corresponds to tongue, and the latin labii used in the Latin Vulgate and Hebrew version.

Genesis 11:4

Wa-qālū ta‘ālū linabī lanā qaryatan wa-majdalan ra’suhu yudāfī al-samā’. Wa- naṣna‘ lanā āsman kay lā yatabbadadu ‘alī wajhi al-ard.

And they said: Come, let us make a city and a tower, the top whereof may reach to heaven: and let us make our name famous before we be scattered abroad into all lands.

The term that appeared in the polyglot bible for city was qaryatun, which means a village or town. This term does not correspond to Bustānī and Yāzijīs’ translation where the word madinatun (city) was used. Similarly, in the latin and hebrew versions, the term civitem (the accusative case of civitas) was used.

Genesis 11:5

Fa-inḥadara malā’ikah li-naẓri al-qaryah wa-al-majdal alladhi banāhu banū Ādam

And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of Adam were building.

The verb for “the Lord came down” used in the polyglot bible was inḥadara which literally means God inclined. This verb isn’t very common in sacred texts. The better verb to use in this syntax is the one used in Bustānī and Yāzijīs’ translation that is nazila (came down).

Also, if we look at the end of the verse in the phrase “which the children of Adam were building”. The children of Adam were building the city and the tower, but the verb used in the Arabic version didn’t respect the Arabic rule of dual endings of verbs.

In Arabic, pronouns are attached to the ending of verbs to show the number. However, Bustānī and Yāzijīs’ translation had the correct pronoun attached to the end of the verb (ban-humā instead of bana-hu).

Genesis 11:8

Wa-baddaduhumu Allāhu min thumma ‘alī wajhi al-arḍi, wa-āntahū ‘an binā al-qaryah

And so the Lord scattered them from that place into all lands, and they ceased to build the city.

This verse starts with the conjunction and so, which translates to fa- a letter that is attached to the beginning of the verb. This was the case inBustānī and Yāzijīs’ translation. However, in this arabic version wa (and) was used.

Interpretations of Genesis 11 through images – The Tower of Babel

Figure 5

The image above narrates two stories, where the notion of time and distance is clearly embodied to separate them. If we look at the front of the image we see Noah planting vines while his son Cham in the right sight of the image is on the ground mocking his brothers. This event is mentioned in Genesis 9. If we look at the back of the image we the the city of Babel where the tower was being built. This event is mentioned in Genesis 11. The fact that the tower is in the background creates a physical distance representing the same time-gap that we see in the texts. Thus, establishing a clear complementary text/image relationship.

Figure 6

This images shows the city of Babel under construction. In the back of the image we can see Tower of Babel completed. Also, we can notice that there are people going into the tower.

Figure 7

This image succeeds in translating verses of the Bible in one image. Looking at the top of the photo we can see God’s eye, looking down from the heavens at the tower the people of Babel were building in hopes to reach him. The clouds and angels around the eye symbolize that the heavens in this image. If we look under the clouds, we can see thunderbolts. These symbolize god’s curse on the tower. This was described in Genesis 11:5 and 11:7 specifically.

Bibliography and References

British Library (2020, 23 November). Christian Arabic Bible Translations in the British Library Collections. Asian and African studies blog.

KNOP, J. A. (1977). The editing and publishing of the London Polyglot (Bible) (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Chicago).

Miller, P. N. (2001). The” Antiquarianization” of Biblical Scholarship and the London Polyglot Bible (1653-57). Journal of the History of Ideas, 62(3), 463-482.

Van Staalduine-Sulman, E. (2018). “Chapter 8 The London Polyglot Bible”. In Justifying Christian Aramaism. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004355934_009