Algonquian Bible / Eliot Indian Bible

Algonquian Bible / Eliot Indian Bible

Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God

by Maïa Peterson

| Title | Algonquian Bible / Eliot Indian Bible |

|---|---|

| Contributor(s) | John Eliot

Cockenoe –translator Wussausmon / John Sassamon –translator Job Nesuton –translator Wowaus / James Printer –translator and printer Samuel Green –printer Marmaduke Johnson –printer John Ratcliff –book binder |

| Date | 1660-1663 |

| Place | Massachusetts, United States of America |

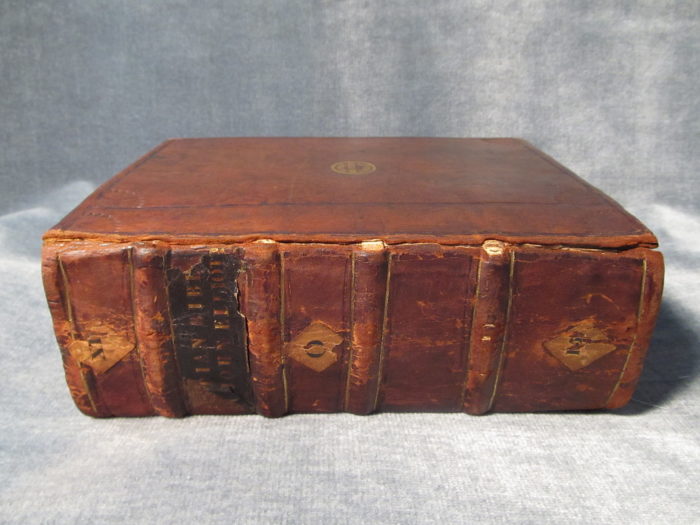

| Format | sheep skin binding |

| Language(s) | Masachusett-Natic, Algonquian |

| Source | Internet Archive – John Carter Brown University |

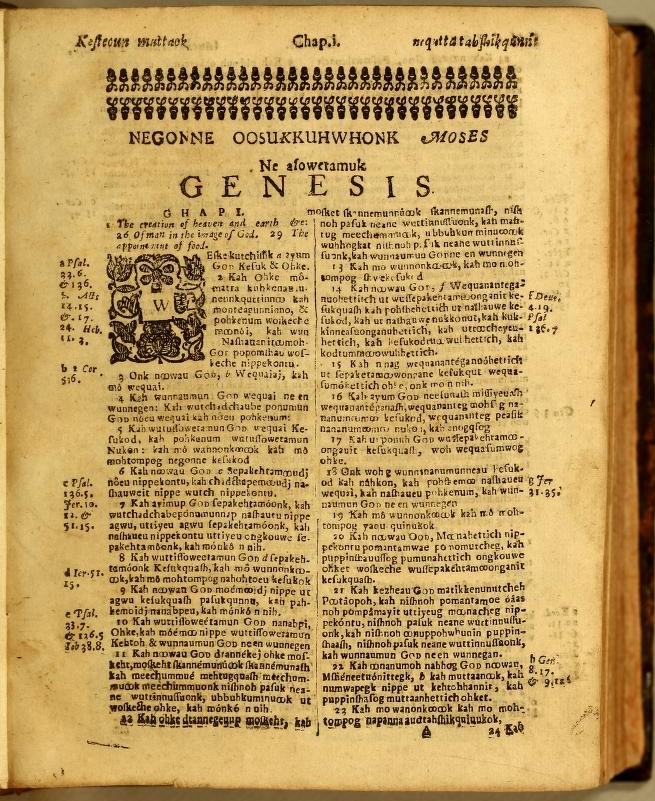

Just twenty years after the Bay Psalm Book was published, the Algonquian Bible graced the ranks of the earliest books printed on British American territory. Also known as the Eliot Indian Bible, named so after John Eliot, the man who organized the production and translation efforts, and the fact that the bible is written entirely in Algonquian, a Native American language that had no written form before this work. The bible was completed in 1660 and by 1663 the “complete translations of the Old and new testaments were printed together in the same 1180 page volume, along with 500 copies of a psalter in Algonquian, Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God,” (Clark, 2003, 16).

Eliot based his translations directly from the Geneva Bible, a staple in Puritan churches, but visually the layout of the Algonquian Bible aligns with the King James Bible, first printed in 1611. There are no images within the thousand page book, instead the the simple filament stamps decorate the header to separate the sections of the bible. It is likely that the simple structure is due in part of the limited resources available to the only printing press in New England at the time, which was located at Harvard, Massachusetts.

This is a second edition reprint from 1685.

Internet Archive.

Item History

A Puritan missionary from Cambridge, England, John Eliot was sent to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1631 to replace the pastor at the time. While there, he was employed by the Society for Propagation of the Gospel in New England, better known as the New England Company, and tasked to convert the natives to Christianity. Sometime in the 1640’s, Eliot would come up with the idea to make an Algonquian translation of the Bible and he would express his need for funding to the Society in several dockets. As he wrote to the organization back in England, he had already taught one Massachusett, Job Nesuton, how to speak and read English while Cockenoe, a Montauk, had taught Eliot how to speak one of the Algonquian dialects (Natick Historical Society). By 1655 Eliot and his numerous translators had completed translating the section of Genesis. They printed out a primer, produced by Samuel Green who operated with the Harvard press, and sent it to the Society to await their approval of the project.

Seen as a potentially exceptional tool to invite and indoctrinate the Native Americans around the Massachusetts Bay territory to the Christianity, the project was supported. In preparation, “Eighty pounds of new type were ordered for the press at Cambridge (with extra O’s and K’s to accommodate Eliot’s transcription of Algonquian phonemes), and the next year journeymen printer Marmaduke Johnson was hired in England and shipped to New England to assist Green on the project, along with more than 100 reams of paper” (Clark, 2003, 13). Back in England, around £16,000 were raised entirely by requesting donations from individuals instead of using institutional or royal finances. With this funding, both the Algonquian Bible and settlements where the converted natives would live were fully underway.

After the completion of the first print runs, bookbinder John Ratcliff, who was sent from London to the Massachusetts Bay Colony by the Society, set to binding 400 of the Bibles specifically for nobles who had invested in the project. All of the books, including Ratcliff’s, were bound with sheep-skin, but the styles differed from elegant to “very rude in appearance, and the paper poor and the type irregular” (Ringwalt, 1871).

Between Green and Johnson, the typesetting was difficult to complete, and praise is given to James Printer, or Wowaus, a Nimpuc, who had been assisting Eliot with the translations alongside his father. “[The Bible’s] completion was in a great degree due to the ability of an Indian apprenticed to Samuel Green. This Indian became a successful typographer, and his name appeared on the Psalter of 1709 in the imprint, B. Green and J. Printer” (Ringwalt). Finally, after the completion of the production, the governor of the New England Company “proudly presented a specially bound presentation copy to King Charles II” in 1664 (Clark, 13).

Genesis of the Project

The middle half of the 17th century would have given Eliot a tremendous opportunity to interact with the many tribes that called the Massachusetts Colony home either as a trader, a passerby, a diplomat, or a witness to the destructive Pequot War just a few years after his arrival. The Pequot War lasted between 1636-1638 and decimated the Native American population that resided along the Connecticut River Valley. What started as disagreements between Native American tribes and their overreach on trade routes eventually turned into a show of force by New England colonial power who stepped into the conflict. The aftermath left the Pequot tribe categorically erased and the survivors were scattered as prisoners of war between the colonially protected tribes. The Native Americans who were not involved directly in the war took a calculated moment to consider the presence of the Europeans. Every month more ships arrived into the Massachusetts Bay, more houses were being built in the colonies, and more land was being purchased from the sachems who needed resources more than they needed an acre.

Illnesses brought by the incoming Europeans had wiped out many native strongholds in the first decade of the 17th century, a war had destroyed an entire tribe, perhaps this was why 5 sachems closest to the Massachusetts Bay Colony asked to be part of their colony and welcomed the missionaries. In 1644, while the New England settlers saw this as a sign that the natives were begging for the gospel, “[Dane Morrison] argues that the Algonquian people, and particularly the massachusett, participated in that project much more actively than is usually represented. […] he claims it should be understood as a strategic accommodation of the British presence in the face of the adversity, rather than as assimilation or capitulation to an enemy” (Clark, 2003, 8). After the Pequot War, the English colonists wanted to find a way to live comfortably alongside their Native American neighbors.

The Praying Towns were proposed as the solution to invite the new colony members as a way to transition their tribal life to a more English one in order to better understand Christianity. Headed by John Eliot and funded by the Society, these Praying Towns were constructed by both missionary and Native Americans. By 1650, “the Nonantum were persuaded to move several miles south along the Charles River, where they were joined by the Neponset, Musketaquid, Pawtuckets, and some Nipmucks to form Natick, the first Praying Town” (Clark, 2003, 10-11) called Natick. It was this community of nearly 200 members that received Eliot’s sermons. Out of his most receptive audience he selected his translators.

Language Use

Algonquian is the parent of a language family group rather than a specific dialect. At the time, European colonialists did not know the differences and when they came across one community who referred to themselves as “Algonquians”, all other Native Americans who spoke or appeared similarly were considered to be versions of Algonquians. By the time that John Eliot arrived to the Massachusetts Bay there was a better distinction between tribes and communities, yet their language groups remained similar enough to be considered Algonquian.

Today, different sources refer to the Algonquian Bible as written specifically in Massachusett, in Wampanoag (both who had a prolific presence in the colony), or in Natick, which also the name of the Eliot’s Praying Town and likely a combination of dialects because of the mix of those living there. It is likely that all of the dialects are represented in the bible due to the numerous translators, all of whom came from different groups. Regardless, the written form of Algonquian changed the way that this language was treated, cared for, and understood as a dozen more religious texts would be printed in Algonquian following Eliot’s grammar book, until 1730 when anglicization of the Native Americans was preferred over comradery. Despite it’s original intentions, the Algonquian Bible is now giving back to the community who use the bible as education source. The Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project utilize the bible as a pivotal tool to revive Wôpanâak culture and language in the very same historic area that brought the Algonquian Bible to life.

Works Cited

Clark, M. (2003). The eliot tracts with letters from John Eliot to Thomas Thorowgood and Richard Baxter. Praeger Publishers.

NATICK HISTORY MUSEUM. (n.d.). The Algonquian and English roots of Natick. Natick Historical Society. Retrieved December 1, 2022, from https://www.natickhistoricalsociety.org/algonquian-and-english-roots-of-natick

Ringwalt, J. L. (Ed.). (1871). American: Encyclopaedia of printing. Ringwalt.